Welcome to The Lineup! This is a weekly column that will examine — you guessed it — nine topics from the world of baseball in numbered order.

1 Hide your kids, hide your kids’ elbows.

With the Little League World Series getting started in Williamsport, Pennsylvania, last Thursday and Japan’s National High School Baseball Championship wrapping up on Sunday in Nishinomiya, it’s a big couple of weeks for youth baseball. And for completely different reasons, the two tournaments illustrate the failure of normative pitcher care in amateur baseball.

Sakushin Gakuin High School took home the national championship by lighting up Hokkaido High ace Kento Onishi, who’d thrown four complete games already in the tournament.

High school baseball in Japan is infamous for pitcher abuse, as news of incidents like Tomohiro Anraku’s 772-pitch tournament in 2013 made waves across the Pacific. And while there’s a cultural inclination for pitchers to throw beyond the point of fatigue in Japan — see Jeff Passan’s The Arm for a thorough explanation — this isn’t strictly a Japanese problem.

American high school and college baseball is rife with pitcher abuse. As the pressure gets higher, short rest and high pitch counts become more common.

However, that might be starting to change. Little League instituted pitch limits for the 2007 season because “take care of your kids’ arms” didn’t resonate enough. Most amateur coaches may have done right by their players, but enough were either ignorant of the dangers of overuse, clinging to outdated notions of toughness, or just wanted to win so much they don’t care, that Little League Baseball itself had to intervene. In June, the National Federation of State High School Associations followed suit, going from an innings-based rule to a pitch-count-based rule.

The norms in amateur baseball right now aren’t strong enough to keep every pitcher as safe as possible, and when norms fail, a just authority steps in to stop the abuse.

2 It’s the age of the breakout catcher.

The Yankees waved the white flag on 2016 by trading Aroldis Chapman, Andrew Miller, and Carlos Beltrán at the deadline, but the next wave of talent is already here. When the Yankees started Gary Sánchez at DH on August 3, the extent of his major league experience had been six hitless at-bats stretched out over the previous 10 months. Since his most recent call-up, Sánchez is hitting .410/.455/.885 with eight home runs in 16 games. He’s dropped so many bombs in the past three weeks that I’d feel pretty safe assuming that he also has more rhymes than the Bible’s got psalms.

Along with Seattle’s Mike Zunino and Boston’s Sandy León, Sánchez is part of a trio of catchers who have shocked the American League with ridiculous hitting displays over the past few weeks. How do they profile going forward?

Sánchez has been on the top-100 prospect list at both Baseball America and Baseball Prospectus in five of the past six seasons, and he’s only 23. But Sánchez’s small-sample breakout feels like it was a long time coming.

In 2009, Sánchez signed for a $3 million bonus — at the time the second-highest ever for a 16-year-old free agent — and then made it all the way to short-season A-ball by age 17. The six years since have kept him in the spotlight so long that the normal growing pains for a young ballplayer have taken on an epic quality; it’s as if Roland Joffé were his Double-A manager. Thanks to the long wait, it’s jarring that Sánchez suddenly looks like he was supposed to: He can handle himself behind the plate just fine, he doesn’t walk that much, and he can hit for both average and power.

Certainly he won’t keep slugging .800 forever, and some sort of struggle is sure to come when the league adjusts, but all signs point to Sánchez catching for the next Yankees playoff team.

Unlike Sánchez, Zunino, who was the third overall pick out of the University of Florida in 2012, didn’t take to the majors so easily. He was the scariest hitter in the best amateur baseball league in the world, and a capable defensive backstop, so it shocked nobody that he spent only a year in the minor leagues before debuting in mid-2013, whereupon he abruptly stopped hitting.

The Mariners gave Zunino a long leash despite his offensive struggles because he’s a good pitch framer, because it’s hard for catchers to hit, and because Safeco Field is a pitcher’s park. But from 2013 to 2015, Zunino hit .193/.252/.353 with a 5.1 percent walk rate and a 32.1 percent strikeout rate, which are about the same numbers Buster Posey would put up if you blindfolded him. At that point, they really ought to take away your bat, send you to the guidance counselor’s office, and suggest that you take up the saxophone instead. The Mariners, presumably unable to procure a saxophone, demoted Zunino last August.

But rather than releasing Zunino, or shipping him out in a my-garbage-for-your-trash trade, new Mariners GM Jerry Dipoto kept him in Triple-A to start 2016, where Zunino figured it out. For the first time, he is crushing big league pitching: .280/.396/.707 in 91 plate appearances. Now, anyone can hit that well in a sample that small, but three things bode well for Zunino in the long term.

First of all, he has that top-prospect pedigree and is still only 25. Maybe this makes me a sucker, but I generally believe that talent lasts; if the star quality was in there once, it’s still there now. Second, Dipoto kept Zunino in Tacoma for half a season instead of calling him up the instant the GM got sick of looking at Chris Iannetta. He let Zunino hit .286/.376/.521 down there for 327 plate appearances, which both convinced the Mariners that the Rezuninaissance was legit and made Zunino himself believe it. Third, the glove is still there. Zunino could hit .250/.330/.420 and still be a really good big league catcher. If he keeps this going through the end of the year, there’s no reason to believe he won’t at least be a league-average catcher going forward.

Lastly, León doesn’t have the bona fides of Zunino and Sánchez, but he is nonetheless hitting .383/.436/.638 in 167 plate appearances for the Red Sox. And that’s good news for Boston, because catcher has been an offensive black hole since Blake Swihart turned out not to be playable behind the plate.

Coming into this year, the 27-year-old León had hit .187/.258/.225 in 235 plate appearances across parts of four seasons with Washington and Boston. At 5-foot-10, 225 pounds, León also lacks the ideal athleticism for a catcher (but no more so than, say, Bengie Molina). But unlike Zunino and Sánchez, León really has come from out of nowhere, and of the three, he’s the least likely to continue to hit long term. Nothing in more than 3,000 professional plate appearances suggests that he’s capable of hitting .300 for any kind of sustained period of time. In fact, León’s .455 BABIP is the highest in baseball by 36 points, which points to luck more than anything else.

The reason for optimism is León’s very good bat-to-ball skills. Among players with 150 or more plate appearances this year, León’s 86.4 percent contact rate is 31st out of 348. His strikeout rate is more pedestrian, but if you can put the bat on the ball, you can develop power later on. I’m personally skeptical, but we’ve seen guys like Yadier Molina and Carlos Ruiz go from offensive millstones to dangerous middle-of-the-order bats after several years in the majors, so there’s at least some precedent here.

Besides, being lucky works just fine over limited stretches of time. We just saw Texas shell out two top-50 prospects to find its star catcher for the stretch run. The Yankees, Mariners, and Red Sox all got theirs for nothing.

3 The Diamondbacks are total clown shoes.

It’s been a rough couple of days for the Arizona front office. With the Braves promoting Dansby Swanson last week and a decision on GM Dave Stewart’s contract option due by August 31, various members of the baseball media have come out with evaluations of Arizona’s front office performance over the past few years. Most notable among these was ESPN’s Keith Law, whose piece reads like that scene from A Boy Named Charlie Brown where Lucy projects Charlie Brown’s faults onto a screen — it is incisive and damning, and it speaks volumes about what happens when you mail in the running of a baseball team.

Then, on Sunday night, Stewart and his boss, chief baseball officer Tony La Russa, fired back through Nick Piecoro of the Arizona Republic. Piecoro’s story quotes La Russa in defense of the ill-fated Shelby Miller trade, sounding like a man who’s been given just enough rope to hang himself.

At any given point, there’s at least one backward-thinking or too-smart-for-its-own-good front office that gets picked on by other teams because of lopsided trades and by national columnists for easy punch lines. But what’s going on in Arizona is worse than what we usually see from the whipping boy of the moment.

Mock the Miller-for-Swanson trade if you like, or the Yasmany Tomás contract, or any move in isolation, but that’s not really the problem. Every team makes head-scratching moves, and the Diamondbacks aren’t as bad as their 52–73 record would suggest: A.J. Pollock has missed the entire season, and Zack Greinke, Patrick Corbin, and Miller have all been worse than could have reasonably been expected.

The problem, as Law says, is that it looks like Stewart and La Russa don’t know what they’re doing. To sign Yoan Lopez to an $8 million bonus only to watch him bust immediately is to be bad at your job. To do that without realizing that the bonus would incur a 100 percent penalty from MLB and effectively take your club out of international free agency for two years is true incompetence. So, too, is giving away one first-round pick (Touki Toussaint) for nothing, then effectively giving up another by not spending to the cap in the draft.

Law lays most of the blame for the Diamondbacks’ failures at the feet of the men running the baseball operations department, but this goes beyond La Russa and Stewart.

It was owner Ken Kendrick who hired La Russa, who may be a legendary field manager but had never worked in a front office before and who holds antediluvian views on baseball tactics and team construction.

La Russa then hired Stewart, who was himself more than a decade removed from an MLB front-office job. Stewart had been a player agent, which is an awkward enough transition, but then neither La Russa nor Kendrick batted an eye when Stewart simply handed over his business to his wife, which all parties insist is totally on the up-and-up and not a grotesque conflict of interest.

It was Kendrick who ran off Justin Upton, and who caused the front-office shake-up that not only ultimately put La Russa in charge, but cost the team A.J. Hinch, one of the brightest young managers in baseball, and replaced him with Kirk Gibson, who executed an organizational directive of lashing out against perceived slights with violence.

Kendrick’s ownership group is now engaged in a pissing contest with Maricopa County over the team’s demand for $65 million in handouts to upgrade Chase Field. That’s a bold request, considering that within the county, the city of Glendale is getting absolutely soaked by its arena deal with the Arizona Coyotes. And, according to Rebekah Sanders of the Republic, it led to county supervisor Andy Kunasek telling Kendrick to go back to “fucking West Virginia.”

Under Kendrick, the Diamondbacks have been insular, anti-intellectual, sloppy, and self-destructively macho — frequently all at the same time. La Russa and Stewart have been an embarrassment, but they’re only the symptom.

The best thing for baseball in Arizona would be for Kendrick to take Kunasek’s advice.

4 Danny Valencia beat the hell out of Billy Butler.

Oakland A’s DH Billy Butler is on the seven-day concussion DL because his teammate Danny Valencia punched him in the head after an argument about a pair of shoes. That doesn’t sound so weird in a post–Chris Sale world, but it’s still a pretty wild piece of clubhouse nonsense.

Valencia’s got something of a reputation for having an attitude, but apparently he was provoked for good reason. According to Susan Slusser of the San Francisco Chronicle, the fight started after Butler told an equipment representative that Valencia had been wearing off-brand cleats in games, even though Valencia claimed he’d been wearing them only in practice and workouts.

Now, that’s a dick move. Slusser reports that Valencia’s failure to wear the correct make of spikes could potentially cost him an endorsement deal worth five figures, so you can certainly understand his being angry that Butler tattled on him. But while a big league clubhouse isn’t a normal workplace, it’s still a workplace, and as a matter of course, it’s not a good idea to go around punching your teammates in the head.

Valencia says he’s put the incident behind him, and several of Valencia’s teammates past and present have rushed to his defense, but Butler, who was the guy who actually got punched, has yet to talk about it publicly. We’ll see if he’s moving on so easily.

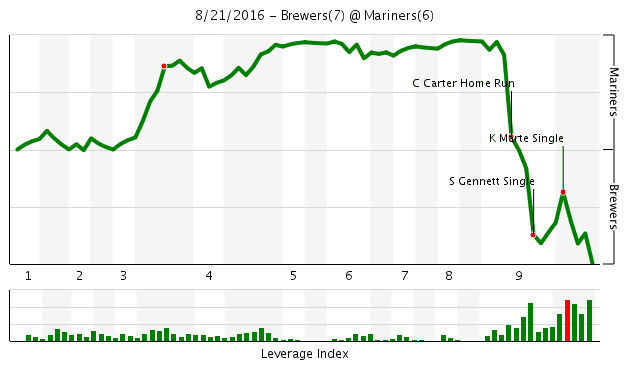

5 The WPA Graph of the Week goes to the Mariners and Brewers.

After all of Seattle’s recent late-game drama, it makes a lot of sense why Edwin Díaz, the rookie closer with the 16.5 K/9 ratio, is so popular out there.

My favorite fact from this game: Seth Smith hit an RBI single in the bottom of the fourth to put the Mariners over 90 percent win probability, and they stayed there until the moment Chris Carter’s home run in the ninth tied it.

6 Josh Reddick joins the bizarre injury club.

As sharp as Dodgers outfielder Josh Reddick is when it comes to identifying staged photos of a sleeping Joc Pederson, he’s a danger to himself when dinner is involved. Reddick injured the middle finger on his right hand by getting it stuck in a door while ordering room service.

While that certainly sounds painful, it fits into baseball’s grand tradition of players suffering bizarre off-the-field injuries.

For no reason other than “I find them funny,” here are my three favorite weird non-baseball injuries:

(3) 1998, Diamondbacks pitcher Brian Anderson’s elbow stiffness: Anderson took a cab to the Rodeo Drive, and while sitting in the back, he rested his throwing arm on the back of the rear seat for the duration of the ride. Well, that was long enough for it to stiffen up to the point where he had to be scratched from his start later that night.

(2) 2005, Rockies shortstop Clint Barmes breaks his collarbone:

Back in 2005, Todd Helton gifted his rookie teammate a parcel of deer meat. Barmes was carrying the package of meat back to his apartment when he tripped while walking upstairs, breaking his collarbone in the process. “Deer meat” starts to sound really funny when you say it out loud two or three times in a row, but this story also tugs at your heartstrings.

First of all, Barmes originally lied about the source of the injury because he didn’t want to embarrass Helton, which is adorably considerate and the polar opposite of punching your teammate in an argument over shoes. And second, Barmes was having a great year. He hit .410/.467/.639 in April before cooling off to .329/.371/.516 at the time of the injury — and he never approached that level again.

(1) 1990, Blue Jays outfielder Glenallen Hill suffers cuts and carpet burns: Hill showed up to work on crutches after a nightmare about spiders caused him to sleepwalk around his house and ultimately fall into and break a glass table. There’s something hilarious about hurting oneself while running from imaginary spiders, but at the same time, we laugh because we all know the spider-attack dream is some serious shit. I had a nightmare once about a spider the size of a golden retriever, and thank God it cornered me instead of chased me around the house. Otherwise, I probably would’ve wound up in the hospital, too.

7 Andrew Miller will put you on skates.

This is just sad:

It reminds me of one of my favorite GIFs: White Sox starter Carlos Rodon, as a college sophomore at NC State, pulling the ol’ antigravity lever on a hitter from Presbyterian College.

But that’s one of the best college pitching prospects of the 21st century knocking over a Big South hitter who’d probably never seen a slider like that before. Miller pulled the rug out from under Khris Davis, who’s not only a big league hitter, but a very good one: Davis has 32 home runs this year, and a career OPS+ of 119, and Miller tied his shoelaces together.

8 Why don’t they make the entire team out of power-hitting infielders?

As if the Astros didn’t have enough power coming from their infield with Carlos Correa and José Altuve, they’ve brought in reinforcements.

Rookie Alex Bregman started out 1-for-32, but he has now reached base in 17 of his past 18 games — a span in which he hit .312/.365/.558 with four home runs. A shortstop who might profile better at second base long term, Bregman has been playing third because Correa and Altuve have the middle of the infield locked down.

Then there’s 32-year-old Yulieski Gurriel, a 15-year veteran of the Cuban league who was perhaps the nation’s best player when he defected in February. Gurriel, a third baseman, signed a five-year, $47.5 million contract with the Astros in July, and after a brief tune-up in the minors, here he is. Gurriel singled in his first big league plate appearance on Sunday, and will play either third himself (moving Bregman to the outfield) or DH.

Gurriel hit .335/.417/.580 outside the U.S., and even though it doesn’t directly affect his play, he’s got a great name for an announcer. Indulge yourself; put on your Harry Kalas or Mel Allen voice and really lean into the stressed syllables.

There are few managers better than Hinch at dividing playing time among lots of different players, but if Gurriel and Bregman both continue to hit, the Astros will have an interesting problem to solve for next year: how to get those two, plus Correa and Altuve, all on the field at the same time.

9 Vaya con dios, Josh Hamilton.

On Tuesday, the Texas Rangers put outfielder Josh Hamilton on release waivers. In strict baseball terms, this is a nonstory. Hamilton hasn’t played all year after undergoing a nonsurgical knee procedure in February, and insofar as the nearly $26 million left on his contract after this year is a sunk cost, it’s already been sunk by the Angels, who agreed to pay all but $2 million per year of Hamilton’s salary when they ran him out of town last year.

With Prince Fielder going on permanent medical leave and the Yankees releasing Alex Rodriguez, it’s been a big month for superstar players with big and complicated legacies saying goodbye to the game. Although Hamilton hasn’t officially retired, his release could very well spell the end of a genuinely unique career.

I believe Hamilton is the most talented baseball player I’ve ever seen — ironically, in part because of the years lost to injury and addiction, which defined him. Anyone who was able to lose three key developmental years to injury and addiction and become an MVP-caliber player anyway has to be a generational talent. Hamilton’s Home Run Derby performance in 2008, his MVP campaign in 2010, and his involvement in the 2010 and 2011 World Series will leave an indelible mark on the game, as will his very public, and occasionally very messy, recovery from drug addiction. Few ballplayers were ever so godlike on the field but so human off it, and if this is the end of his playing career, I wish him luck with whatever comes next.

All stats are current through Tuesday afternoon.