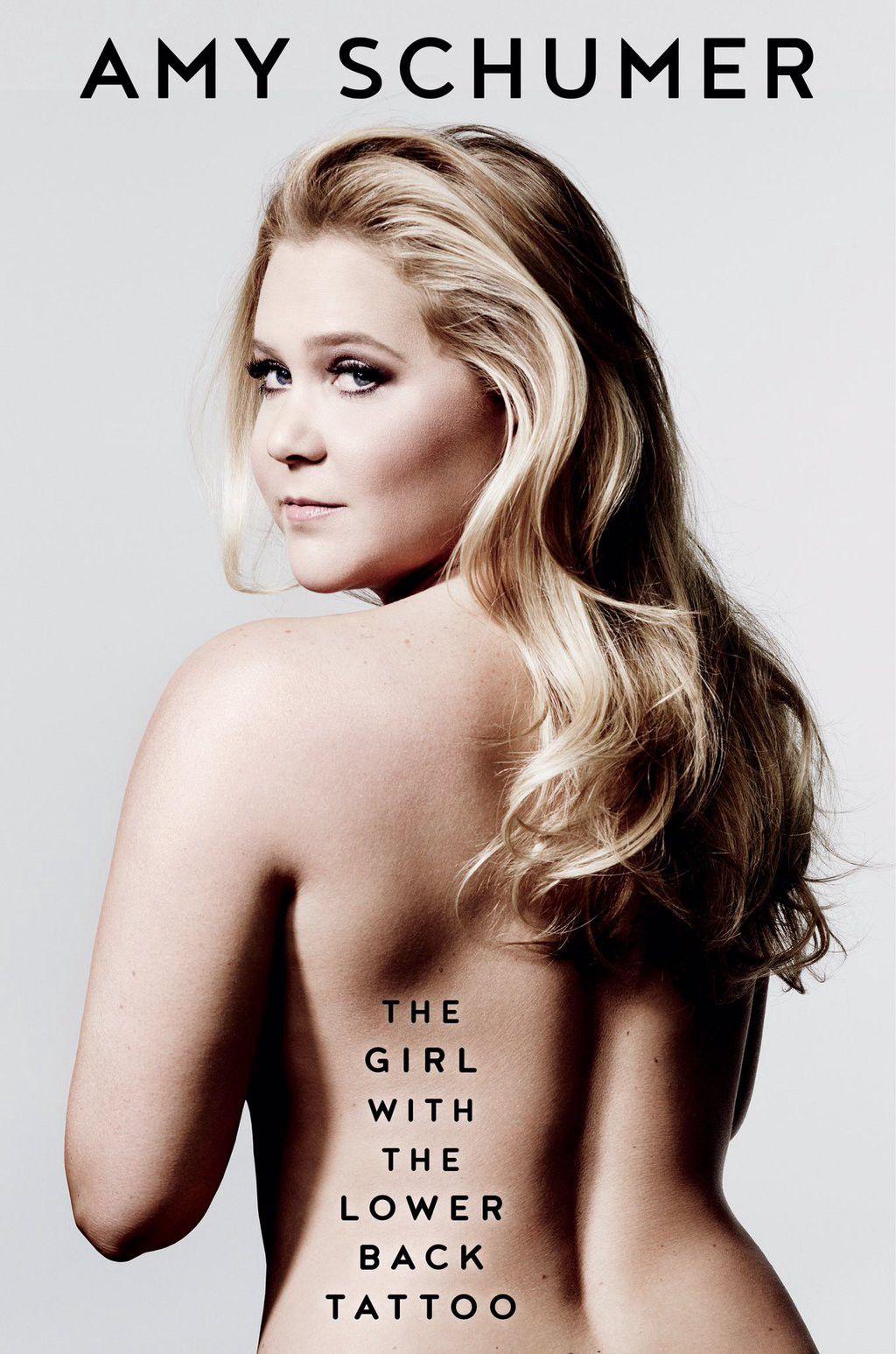

In 2013, Amy Schumer — then a rising stand-up comic with a brand-new Comedy Central show — sold a book to HarperCollins for a reported $1 million. A year later, she canceled that contract, claiming — understandably — that she was too busy to complete the project. Then in 2015 — the year of her meteoric rise to superstardom and cultural ubiquity — she sold a similar book to Simon & Schuster, to a figure The New York Times reported to be between $8 million and $10 million. No shade: It was a savvy move. “For years now, every agent in town would use the [$6 million] Tina Fey advance [for her book Bossypants] as the benchmark for what their celebrity client was worth,” the president of HarperCollins was quoted saying in the piece. “Now the bar is sitting atop Amy’s head.” He said he was not surprised, in the end, that she withdrew her HarperCollins contract when her career was in transition: “She knew that delaying her book would reap huge benefits when the time was right.”

But when Schumer’s book, The Girl With the Lower Back Tattoo, arrived in stores on Tuesday, the timing felt a little awkward, if not downright unfortunate. Schumer had a deservedly glorious 2015: a terrific, Emmy-winning season of her show, a hit summer movie that she wrote and starred in, an HBO stand-up special directed by none other than Chris Rock. But her star rose so quickly that year that 2016 has found her playing catch-up: The fourth, relatively lackluster season of Inside Amy Schumer came and went with little fanfare, perhaps because, as a bona fide movie star, it seemed as though her career had outgrown the modestly rated half-hour-premium-cable-show moment and sky-rocketed right to the “she seems way too famous to be doing an Old Navy commercial” moment. (Why does every comedian who does an Old Navy commercial seem way too famous to be doing an Old Navy commercial? Does Old Navy have some kind of blackmail-worthy dirt on every A-list celebrity? I want answers!)

2016 has no doubt been a transitional year for Schumer. This has become abundantly clear in the few days since the book came out, when an online controversy emerged surrounding her friend and Inside Amy Schumer writer Kurt Metzger. Metzger, a self-identified “rape apologist” who has a long history of disturbing behavior toward women, continued his streak this week when he began making controversial (read: really fucking stupid) comments online about sexual assault in the comedy community. Many fans demanded that Schumer fire him, or at least explain why she continued to employ a man who so directly contradicts the feminist ideas at the core of her show. On Twitter, Schumer blocked many of the people who questioned her about this, and then, late last night, she tweeted that Metzger was no longer employed by Inside Amy Schumer because there was no more Inside Amy Schumer. She seemed uncharacteristically defeated in the way she revealed this, closing one chapter of her career with a whimper rather than a bang. Then, this morning, she claimed the show was in fact not over, but simply on extended hiatus.

Which makes the timing of her book release seem stranger than ever.

It sometimes seems as though there is a universal mandate that every Successful Female Comedian in the 21st Century must write a book. A particular kind of book, of course: Not a novel or a travelogue, but a collection of personal essays that might be described as “raw” or “confessional,” intercut with lighter, page-and-a-half-long palate cleansers like “Things That You Don’t Know About Me” and “An Open Letter to My Vagina” (two chapters from Schumer’s book).

The Girl With the Lower Back Tattoo is a textbook example of what, in 2012, the writer Kaitlin Fontana dubbed “the Femoir” — a memoir of “awkward, soul-bearing confessions” written by a “contemporary female comedian.” Surely you’ve read at least one of these books, or at least considered buying one at an airport; they’re everywhere, and their popularity only causes them to multiply. “[T]he Femoir,” Fontana wrote, “while not unique from its male counterpart, is, in marketing parlance, So Hot Right Now. You can be a male comedian and not write a memoir. But if you are a female comedian, you would be stupid not to.”

That prophetic piece was written only a year after the release of Tina Fey’s Bossypants, which — judging from overall sales, critical reception, and continued subway ubiquity — is now probably the high-water mark of the genre. Sure, there were “femoirs” before Fey (the droll soul who would probably delight in knowing that my computer keeps correcting “femoir” to “femur”). Nora Ephron was an obvious early pioneer of the genre, with her now-legendary self-deprecating (yet elegantly dignified) collections Wallflower at the Orgy and, much later, I Feel Bad About My Neck. Arguably the mother (er, mistress?) of the 21st-century femoir is Chelsea Handler, whose run of candid, gloriously raunchy best sellers, beginning with 2005’s My Horizontal Life, proved there was a large market for this type of book, the more candid the better. Sarah Silverman took the genre to darker depths a few years later with The Bedwetter. But après-Bossypants came the deluge: Amy Poehler’s sharp self-help scrapbook, Yes Please; Mindy Kaling’s pair of light comic tomes, Is Everyone Hanging Out Without Me? and Why Not Me?; and of course, Lena Dunham’s smartly written lightning rod for controversy, Not That Kind of Girl. By the time Dunham published her entry into the modern femoir canon, it had become such a recognizable type of book that she gave it a winking subtitle poking gentle fun at the cliché: “A young woman tells you what she’s ‘learned.’”

But the reception of Dunham’s book showed the frustrating double-bind that many of these authors are caught in: In the age of social media, we crave increasingly “intimate, confessional” stories from celebrities (female celebrities in particular), but as soon as they share a detail that paints them in a less-than-heroic light, the Problematic Police are quick to pull them over. Because of a scene in Not That Kind of Girl in which Dunham describes a childhood memory of curiously parting her younger sister’s legs to look at her vagina, right-wing pundits who already had an ax to grind with her dubbed Dunham a “sexual predator.” Our collective desire for salacious details is matched only by the extent to which naysayers and fans alike will pore over every word of these books, and reject authors the second they find them lacking.

Ever aware of this, Schumer’s book crackles with anxiety about the fraught environment into which it will be released. (There are caveats like “That’s not racist because …”) In an early chapter, she makes an observation about her 2-year-old niece’s obsession with a certain stuffed animal. “I hope she isn’t like that with dudes when she grows up,” Schumer writes. “Or chicks. Or maybe she won’t identify as female. Whatever she does will be fine. Or he.”

“Damn,” she concludes, perhaps a little prematurely, “it’s hard to write a book and not get yelled at.”

In her 35 years, Schumer has certainly lived through a book’s worth of tribulations. Her parents once owned a boutique children’s furniture company in Manhattan, but lost the business and much of their assets when Schumer was about 9. Not long after, her father was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis and her mother had an ill-fated affair with Amy’s best friend’s father, causing a permanent rift in her daughter’s most important friendship. Throughout all of this, her mother would repeat to Amy and her siblings the chirpy mantra “you’re okay,” “in an upbeat tone that tricked [them] into believing it.” Schumer writes, “This is how we were raised: we were always oppressively OKAY.”

The two most devastating chapters in the book chronicle two early romantic relationships. Judging from its title and the tone of Schumer’s stand-up, you’d expect “How I Lost My Virginity” to be a humorous piece about bad and catastrophically awkward teenage sex, but instead it’s a harsh account of thwarted expectations. “I imagined looking the man I loved right in the eyes and kissing him and smiling and intertwining our fingers and then two becoming one and the whole thing being slow and beautiful,” Schumer writes of how she’d always imagined the act. In reality, when she was 17, she woke up from a nap on her boyfriend’s bed to find him entering her without her consent. Jarringly and powerfully, the chapter doesn’t end with the comfort of a joke or a lesson. “[H]e just helped himself to my virginity,” she writes, “and I was never the same.”

Ditto for a harrowing chapter called “The Worst Night of My Life,” in which she chronicles an abusive relationship she endured in her early 20s. And then, of course, there’s a piece toward the end of the book in which Schumer grapples with the deadly shooting that took place at a Louisiana screening of Trainwreck. She educates the reader with statistics about women and gun violence (that we know she’s survived an abusive relationship gives these facts a personal urgency), and even includes an appendix in which she lists every congressperson who has received money from the gun lobby. The chapter is titled “Mayci and Jillian,” in honor of the two victims.

These pieces fit strangely with the rest of the book. Some of these wounds still feel too fresh for Schumer to have fully processed, and at times you can feel her straining to find humor and pithy wisdom — simply because that is how you write one of these books.

In April, Schumer was the subject of a Vanity Fair cover story that asked in its headline, “Amy Schumer Is Rich, Famous, and in Love: Can She Keep Her Edge?” The piece was a portrait of a celebrity at a crossroads, setting out to prove that her game-changing year of 2015 wasn’t just a fluke. She admitted that these changes in her lifestyle had her reconsidering what does and doesn’t make for good, relatable material.

“[N]obody’s like, ‘Tell us more about what it’s like to be a famous person!’” she said. “But there is that too. It’s like my experience now is of a normal woman, who’s 34, who’s in a relationship, and then I’m also a pretty newly famous person, and that’s what I want to talk about onstage.” She wondered how someone as successful as, say, Jerry Seinfeld navigates this gap between his own lifestyle and his audiences. His set, she mused, can’t possibly rely on jokes like, “Private jets — right, you guys?”

“I want to be honest about what’s going on with me,” she added, “and not be like, ‘I’m still just like you!’ I don’t know. I’m trying to navigate it honestly and figure it out.”

But The Girl With the Lower Back Tattoo was written by someone for whom the giddy novelty of new fame has not yet worn off, and that gives it an off-putting tone. It’s a little too Private jets — right you guys?, in that there is a section about … private jets. (“When you fly private, a car drives you right up to the runway at the exact time your flight takes off. You want to take off at 9:00 p.m., your car drops you there at 8:55 p.m.!”) And that chapter is called — I kid you not — “On Being New Money,” and it’s written by someone who doesn’t yet have the perspective on this experience to derive much meaning from it.

I wish this chapter were an outlier, but there’s another one called “Athletes and Musicians”… which, yes, is basically just about hooking up with famous athletes and musicians (she doesn’t name names, which is nice because she demeans a few of these guys in such a way that I actually felt sorry for them). A chapter called “NYC Apartments” (already a topic that no one ever needs to write an essay on ever again) spends way too much time musing on how great it was when she recently bought her own NYC apartment. Good for her. She also writes about her recently purchased wine fridge, and a portrait of her stuffed animals that she commissioned Tilda Swinton’s partner to paint.

I expected Schumer to find a smarter and more palatable tone when talking about her new wealth and fame, because she’s found a way to do it in her recent stand-up. I saw Schumer live twice in 2015 (doing a set similar to the one you can watch in Amy Schumer: Live at the Apollo) and both times she killed. After seeing her the first time, right before the release of Trainwreck, I wrote, “Maybe the most revolutionary thing about Schumer’s comedy right now is that she’s speaking truthfully from the inside of success — but still candidly reporting on its disappointments and the ways in which achievement is never simple when you’re a woman.” In that set, she named names and called very specific bullshit on Hollywood, famously joking that Rosario Dawson should have gotten an Oscar for Zookeeper, because “let’s see Meryl pretend to want to fuck Kevin James for six months.” But her essays are not nearly this incisive, resulting in a book that is meant to make us feel more intimately connected to her but instead just makes us feel more estranged from her.

This was not the right time for Amy Schumer to write a book. I mean this for reasons that include, but go far beyond, the Kurt Metzger controversy — this is one of many nuanced things in her life that I just don’t think she’s had the appropriate amount of time to reflect on yet. But on a larger scale, she’s still in a transitional moment of adjusting to major changes in her lifestyle. Wealth, fame, and power are still novelties to her in a way that they would be to you or me if we became that famous that quickly. They are novelties to her in a way they weren’t to Tina Fey and Amy Poehler when they wrote their books, and that is one reason why theirs are better books.

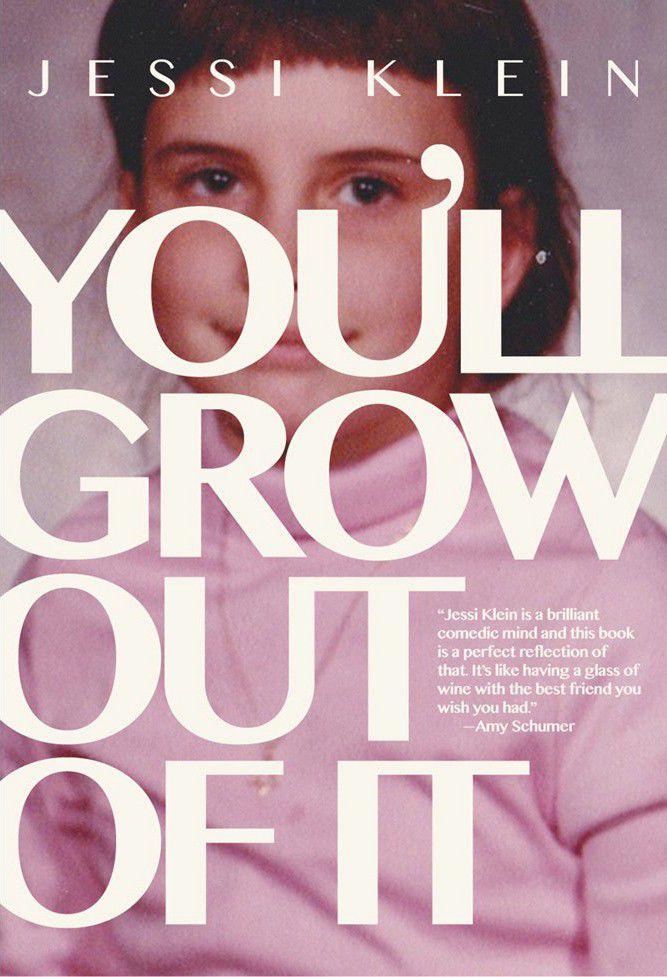

Stand-up comedy and essay writing are different skills, so it’s strange that we’ve created this expectation that a person who’s good at one must be good at the other (or able to find a ghostwriter skilled enough at making us think they’re good at the other). Occasionally, comics are great at both: Schumer’s head writer, Jessi Klein (a whip-smart stand-up comic in her own right), recently published a hilarious, poignant, and all-around-excellent essay collection called You’ll Grow Out of It, which I cannot recommend highly enough. But stand-up relies on instant gratification and constant tweaking based upon audience reaction; writing a book involves stepping away from your work and having the confidence to let it stand as your last word on a matter. Schumer possesses such an acute talent for the former that it hampers her ability to achieve the latter. You can feel her itching to edit this book as she goes, based on what the audience does and doesn’t find funny. That’s not necessarily a weakness; that’s just how stand-up, the thing she’s best at, works.

I hope The Girl With the Lower Back Tattoo is the beginning of the end of the femoir as we know it; the book is uneven and formulaic in a way that suggests there just isn’t much life left in this genre. This is not to say the femoir didn’t have its moments — I will stan for most of Bossypants and The Bedwetter until the end of time, and Klein’s book is one of the best things I’ve read this year — but reading Schumer’s book makes me feel like the well has been tapped. It’s particularly awkward to watch her try to fit the traumas of her life — familial illness, sexual assault, and the fallout of gun violence — into the easily recognizable microgenre of celebrity memoir. The femoir in its current state fails the celebrity author as much as the reader: It demands that women find a way to cram their most nuanced, unwieldy experiences into a very particular box. But the sides are beginning to tear. It’s time for something new.