“I can no longer stay silent.”

So proclaimed Michael Jordan, the most notoriously apolitical pop culture figure of his generation, as he surveyed the grim aftermath of a tumultuous July that saw the video-recorded death of a black man at the hands of police in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and an ambush on cops in the same city that resulted in the deaths of three officers.

“As a proud American, a father who lost his own dad in a senseless act of violence, and a black man, I have been deeply troubled by the deaths of African-Americans at the hands of law enforcement and angered by the cowardly and hateful targeting and killing of police officers,” Jordan wrote on The Undefeated.

In 2016, few were clamoring for Jordan’s statement on race relations in America — whether his alleged “Republicans buy sneakers, too” quip is real or not, it informs how the public views him as a political figure. But the former NBA star still felt compelled to wade into a highly contentious topic. Why? Was it a visceral reaction to the video footage captured in Baton Rouge; Dallas; and Falcon Heights, Minnesota; that has ricocheted across the web for weeks? Was it the groundswell of online activism that reached across races and demographics? Or the pang of his own conscience?

Perhaps it was a mix of all three; we can’t know. But his phrasing — “I can no longer stay silent” — has become a common refrain in the recent online discourse about race in America. “There’s an idea in the scholarship of social movements … called threshold effects,” said Deen Freelon, an associate communications professor at American University who has studied online activity related to the Black Lives Matter movement. “You have to be able to see people in your network interacting with [an issue] a certain number of times to be able to engage with it. But everybody’s threshold is different.”

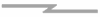

In July, a lot of people’s thresholds were reached. According to Twitter, the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter was tweeted 6.6 million times, more than it was during the 11 previous months combined. Facebook declined to share data about race-related discussions on its platform, but if your News Feed looked anything like mine, it was full of people speaking for the first time about police violence against blacks. Though the phrase was coined in 2013 and reached widespread use in 2014, the mainstreaming of #BlackLivesMatter began in earnest in 2016. What was once an online rallying cry is now popping up in the streets, at presidential primary debates, and at the Super Bowl.

The reasons that Michael Jordan or Beyoncé might join the Black Lives Matter movement aren’t necessarily different from the reasons the average person may do the same — and the effect of their influence isn’t so different either. We all have what Freelon calls “political capital” that we are spending every time we publicly identify with a social cause. The impact may feel small, but collectively, our words have the power to change which topics air on the nightly news or appear on a politician’s campaign platform.

This is how a movement spreads in the 21st century — not just with picket signs and bullhorns, but with “likes” and retweets. Like so many internet phenomena, #BlackLivesMatter has gone viral. But as the movement touches more people, it’s harder to guess the intentions of the individuals who brandish the phrase and how their messaging impacts the real world.

When we think of memes, we think of cats, anthropomorphic sharks, or Arthur. But social justice movements are often meme-like in nature, too, with a few key differences. Take gay rights activism: In March 2013, as the Supreme Court prepared to rule on California’s same-sex marriage law, the Human Rights Campaign asked its online followers to change their Facebook profile pictures to a red equal sign in support of marriage equality. Within a week, 3 million users had made the change (a similar campaign that began after the 2015 Supreme Court decision that gave same-sex couples nationwide the right to marry garnered 26 million participants).

Facebook performed a study looking at how the 2013 campaign’s virality differed from typical internet phenomena. Generally speaking, messages online can spread rapidly either via simple or complex diffusion. In a simple case, a person needs to be exposed to a message only once before they feel compelled to share it. For example, here’s how the study’s findings would play out if applied to, say, the Dress: You see the Dress, proclaim that it is white and gold, and immediately ask your Facebook friends what they think. Because the Dress is mindless web minutiae, there is little social risk in sharing it.

In the complex-diffusion process, messages have a higher tipping point. People are more reticent to make political statements online, so they need multiple exposures to an idea before they are willing to share it, a process known as complex diffusion. Facebook’s study found that users were more likely to adopt the equal-sign logo as they observed more and more of their friends using the picture. Seeing a single friend use the image caused the biggest increase in likelihood of user adoption; seeing a second friend caused a smaller, but still significant, increase, and so on, up to the eighth friend. Once a controversial or fringe activity is normalized in a person’s peer group, that user feels more comfortable participating.

“The equal-sign movement appears to have required more social proof than most copy-and-paste memes, showing that most individuals need to observe several of their friends taking the action before social proof is sufficient to justify deciding to engage in the action themselves,” the researchers wrote.

The need for the so-called “social proof” likely applies to the Black Lives Matter movement as well, which has less national support today than gay marriage did in 2013. The phrase was coined three years ago by the activists Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi in response to George Zimmerman’s acquittal on murder charges for the shooting death of Trayvon Martin. The trio established an activist network of the same name, which has organized protests nationwide since the death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014. But the hashtag has taken on a life of its own, becoming a widely used symbol of allyship with the activist movement and representative of a long list of black people who have died in encounters with police in recent years.

“When you make that [#BlackLivesMatter] post, what you’re doing is creating a kind of public substantiation of your personal civic identity. ‘This is something I believe in, this is a movement I want to align myself with,’” said Erhardt Graeff, a researcher at the MIT Center for Civic Media. “The folks that are in your network may see that and feel that in some ways that movement is now closer to them because they’re connected through you.”

Network effects help explain how #BlackLivesMatter spreads generally, but there were more specific reasons that the hashtag exploded on Twitter in July. For one, the world was subject to two horrifying videos of black men dying on back-to-back days. In the first, Alton Sterling was shot by officers outside of a Baton Rouge convenience store while he was pinned to the ground; in the second, Philando Castile was shot and killed during a traffic stop in Falcon Heights, Minnesota. (In both cases, police have claimed the men were reaching for guns.) Cellphone footage recorded by observers — and in Castile’s case, streamed live on Facebook by his girlfriend — immediately presented the world with visual accounts of what transpired before police or media outlets could establish a narrative. This kind of citizen journalism can be an especially provocative rallying point, experts say.

“It’s a really powerful reframing to have folks on the ground — particularly people of color — who didn’t necessarily have access to mainstream newsmaking in the past, to show these clips — show what’s happening through their own eyes or their camera lenses — and tell the story on their own terms,” says Brooke Foucault Welles, a communications studies professor at Northeastern University.

Once the videos began circulating, many people viewed them as part of an ongoing narrative concerning undue police brutality against blacks. That’s in part because of how Black Lives Matter activists have framed previous killings as a function of systemic racism in American society, researchers said. In the two years since the Ferguson protests, nonactivists were exposed to this message, so yet another killing is more likely to push them to a social breaking point — the point where they “can no longer stay silent,” Freelon explained.

“If it’s just an isolated incident, there’s no reason for you to spend your political capital on this,” he said. “One of the most important things Black Lives Matter did … is they sort of helped a wide swath of America, not just black people, to see what’s going on not as a set of isolated incidents, but as a repeating pattern. Then you begin to see individual events as part of an ongoing pattern of injustice.”

Also, unlike some internet movements, Black Lives Matter has a consistent feedback loop with the real world. Online outrage is leveraged to coordinate flesh-and-blood protests. More than 1,400 events have been held since July 2014, according to Elephrame, an online encyclopedia that crowdsources news and social media reports about protests. Those demonstrations attract media attention, beaming news of the killings to a wider audience, which then voices its opinion about the topic online — perhaps using the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter.

“The more attention focused on a single point or single event, the more diverse the [online] conversation became,” said Freelon, who tracked Black Lives Matter–related discussions on Twitter from June 2014 to May 2015. “When there wasn’t a whole lot going on news-wise, it was mostly a black and activist conversation. But during those really hot events — Ferguson and some of the major legal developments that occurred — that was when the nonblack public was really paying attention to it.”

In late July, as the country was reeling from the Sterling and Castile killings, as well as the attacks on police officers in Dallas and Baton Rouge, former Michigan Governor Jennifer Granholm took to Twitter to proclaim that Democratic vice presidential nominee Tim Kaine was “woke.”

To get it out of the way: Tim Kaine is not woke. Being woke involves taking knowledge about social and political systems working against you and using it for self-preservation. A person like Tim Kaine, a United States senator, broadly benefits from those systems.

But the argument about what “woke” specifically means is largely irrelevant — the term itself is already falling out of favor in some circles. What matters is that the nebulous concept has attracted a large amount of currency on social media. People online crave to be described in such terms, to be recognized not only for being on the right side of history, but for being one of the cool kids on that side. The desire for “wokeness” is the logical outcome of an online world where any social justice proclamation will be tagged with an accompanying score: album sales, YouTube views, Facebook likes.

So how can we know that a person is doing the right thing for the right reasons, or if they’re engaging in, as Freelon called it, “performative wokeness”? In short, we can’t. “There’s a lot of questioning of folks’ motivations. To a certain extent, that’s something that’s hard to get at because you can’t ask people about that,” he said. In his study, he found that 60 percent of the users who posted the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag only used it once over the course of a year. “I think a lot of that is just them glomming onto the event of the moment. Maybe their level of interest in [the movement] is not that great.”

But even questionably motivated social justice demonstrations can lead a person on a path of self-discovery, Foucault Welles said. “Folks do a lot of sense-making and identity work online. So, if you temporarily change your profile photo to say Black Lives Matter … maybe then you’re more emboldened to say that in your face-to-face conversations. Once you kind of take a public stand like that, it creates some dissonance if you then don’t follow through.”

Celebrities’ use of phrases like Black Lives Matter allows for an examination of how the dynamics are playing out nationwide. Following the death of Sterling, actress Olivia Wilde used the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag on both Instagram and Twitter, attracting both praise and invective from her followers. Many celebrities of all races responded to the attack as well.

“I think it matters that people like Olivia Wilde are tweeting with the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter because I think that reaches a certain audience that black celebrities might not reach,” says Sarah Jackson, a communication studies professor at Northeastern University and author of the book Black Celebrity, Racial Politics, and the Press: Framing Dissent. “But I also don’t think people like that are necessarily going back into their communities or into the entertainment industry and saying, ‘OK, how do we apply the principles of this movement to our everyday lives? How do we agitate? How do we protest?’ That’s OK if that’s not what they’re doing, but I think it depends on how we’re rating sincerity and commitment.”

Celebrities such as Wilde — or even nonfamous users who have mostly white followers — are likely reaching individuals on the periphery of America’s race discussion. A new study by the Pew Research Center found that 68 percent of black social media users reported encountering a significant number of posts about race online, while just 35 percent of white users did. Fifty-seven percent of black users have made a race-related post on a social network, but less than a third of all white users have (it’s worth noting that Pew’s research was conducted before the July shootings). For some social media users, the discussion of race relations in America feels omnipresent; for others, it’s not even happening.

But engaging those peripheral users is key to spreading a movement online. “Some recent studies are starting to see that the periphery itself is important in the actual spread,” said Giovanni Luca Ciampaglia, a research scientist at the Indiana University Network Science Institute. “You’ve got to get out from the core, from the central, active user, if you want to disseminate widely. Even though people might be talking about something only once or twice, in terms of the cascades of information, the periphery is still very important in terms of the reach.”

The researchers I spoke with mostly agreed that people who spread an activist message provide benefit to the movement, even if their individual motivations remain unknown. “Spreading the message is valuable even it doesn’t go beyond that,” said Jackson. “I sort of reject the idea that people would support the Black Lives Matter movement just to get attention. It’s not as if the Black Lives Matter movement is the Ice Bucket Challenge, which is really uncontroversial. If you want to get positive attention and you’re just concerned about getting a wider audience … you could support breast cancer research or helping kids learn how to read. The issue of race in the United States and talking about race and talking about inequality — even in the phrase ‘Black Lives Matter’ — is still an extremely controversial thing to do.”

The ultimate goal of the Black Lives Matter movement is not to launch trending topics or help internet users earn a wokeness badge. The goal is to stop the unjust killing of black men and women by police (among several other concrete policy proposals). Do social media posts bring these demands closer to reality?

Specific proof is hard to come by. Freelon is currently studying the question by looking at how lawmakers are influenced by tweets related to the Black Lives Matter movement. “Our argument is a politician has to be engaged on the issue before they can sponsor legislation,” Freelon said. “It gets the attention of people who have the potential to pass laws.”

It’s also hard to track how many people are galvanized to go from writing a racial-justice post on Facebook to brandishing a picket sign in the streets. Anecdotally, local activists groups told The Washington Post that they had seen an increase in membership following the killings of Sterling and Castile, but nationwide metrics don’t exist. “It’s really hard to say strongly whether there is what’s called a ‘ladder of engagement’ — as in, people engage with something in a very small way and then they move up this ladder of engagement to organizing something in their hometown, creating a group, becoming a leader of the movement,” said Graeff. “There’s all these hopes that we have that these things will escalate in those ways, but we still don’t have the data to say how much of this happens.”

Part of the reason it’s difficult to track the Black Lives Matter movement’s success is because it remains largely decentralized. There is no one figure who can command national attention with fiery speeches, and while many localized groups are lumped together under the BLM banner, they often have competing goals. Additionally, recent events led to some users repurposing to attack the movement. In the 10 days after the July 7 killing of five officers in Dallas, 39 percent of tweets using the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag voiced opposition to the movement, up from 11 percent in the days before the shooting, according to the Pew study. Supportive #BlackLivesMatter tweets tumbled from 87 percent to 28 percent because of the Dallas attacks. “This has always been an issue for social movements,” Graeff said. “They’ve always struggled when they give some ownership in the campaign to the wider public [because] that could go in the wrong direction and hurt the campaign in some way.”

But that lack of central control is also what grants the movement so much power online. Anyone, at anytime, can launch into a conversation on race and know that the people closest to them will be listening — in fact, recent changes to Facebook’s News Feed mean that someone in your friend list writing about the issue will likely be given greater precedence than a news outlet covering the same thing.

“This is what all the best social movements do — is to help people see an event that they were sort of aware of to some degree in a new light,” said Freelon. “This was the great success of the civil rights movement, being able to help folks see just how terrible Jim Crow really was. TV helped with that in the ’60s, and social media is helping with it now.” Users might not have the power — or desire — to wave a sign and rally the masses, but they have the potential to change some minds close to them with a few keystrokes.

“The more people acknowledge that it’s a problem, say that it matters to them, say that solutions matter, then I think the more mainstream the conversation becomes,” Jackson said. “I think there will always be a segment of the American population that’s uncomfortable with the conversation, but I actually think it’s really remarkable if you think just in the last couple of years how quickly this conversation has become one that almost everyone has something to say about.”