Can Great Movie Directors Make Great TV?

This week, Baz Luhrmann becomes the latest high-budget film director to jump to the smaller screen, and not without some struggle. Here, our five lessons from TV’s auteur boom.

Halfway through the mega-super-ultra-deluxe-sized pilot of Baz Luhrmann’s first TV show, one thing is obvious: This is definitely Baz Luhrmann’s first TV show.

The Get Down’s first installment is rife with issues, and issues particular to its director. (Luhrmann cocreated the series — which debuts Friday on Netflix — and also serves as an executive producer.) Overlong, overstuffed, and overindulged, it’s by far the weakest of the advance episodes provided to critics. Which is a problem, because a pilot is the only first impression a show will ever make — and because The Get Down’s is inextricably tied to the superstar director who got the series green-lit in the first place.

Including the show’s well-documented production troubles, The Get Down raises questions about the tradeoffs required to lure a Luhrmann-level name to television. Unleashed just two weeks before the show’s long-delayed release, Variety’s deep dive into The Get Down’s tortured, costly development reads like the perfect storm of Peak TV: a patron with (functionally) unlimited coffers meets an artist with an unlimited capacity for depleting them.

According to reporter Cynthia Littleton, Netflix wouldn’t order The Get Down to series until it guaranteed Luhrmann’s hands-on involvement, an arrangement that’s yielded double-edged results. All of Luhrmann’s signatures are present and accounted for, both good and bad: lush production design; camp sentimentality; showstopping music and dance sequences; and an eye-popping production budget of $120 million, a per-episode average equal to Game of Thrones (and a total higher than his last movie, The Great Gatsby, which did not exactly look cheap).

Unlike Gatsby or any other feature, though, The Get Down won’t have to stand on its own at the box office. Staggering as it may seem, $120 million is just 2 percent of Netflix’s $6 billion original content budget. And thanks to the streaming service’s subscription model and murky ratings data, The Get Down would be impossible to write off as a financial failure, even if it becomes a critical one. Which it probably won’t: Initial stumbles aside, The Get Down is vibrant and joyous, hitting more of its stride with each passing episode. It won’t put an end to Netflix’s unstoppable sprawl, nor Luhrmann’s career.

What it might do, however, is complicate a largely unquestioned assumption: that the slow but steady migration of A-list directors into television is an unalloyed good, the final legitimizing of television’s 70-year history as an art form (and the nearly 20-year sprint to the finish of the so-called Golden Age). On the occasion of the trend’s highest-profile release yet, and with more examples cropping up by the week, it’s time to survey the field. Could the future of television be as simple as transplanting artists from one medium to another? More importantly: Should it be? A case-by-case look at directors’ efforts offers some takeaways that suggest the answer is, at best, complicated.

Know What You’re Buying: Baz Luhrmann, ‘The Get Down’

What’s most telling about Variety’s behind-the-scenes piece isn’t that Luhrmann went over budget, which was basically a given — it’s why. Littleton writes: “[Luhrmann’s] unfamiliarity with the episodic TV production process showed from the start, according to sources who faulted Luhrmann for failing to heed the counsel of seasoned veterans and for showing a lack of regard for the skills needed to pull off a big-budget drama series.” Earlier, she notes, studio execs at Sony TV, The Get Down’s production studio, floated the idea of bringing on a more experienced showrunner to ease Luhrmann’s transition, only for Netflix to dismiss it.

Compared to film, or at least to the big-budget studio films made by directors like Luhrmann, television — even top-of-the-line cable and streaming television — typically requires far more material for far less money. It’s only natural that Luhrmann would have difficulty adjusting to these kinds of constraints, and even though the logic behind refusing to assign him a showrunner is flawed, it still makes a certain kind of sense: Baz Luhrmann is what Netflix is paying (and paying, and paying) for, so Baz Luhrmann is what they want to get.

But with Luhrmann and many of his peers, that thinking has fed into a prestige arms race that’s yielded shockingly little in the way of actual television. HBO, Netflix, Amazon, and the like are desperate to work with top-line directors, and in return, they’re making unheard-of concessions to auteurs’ demands and schedules. In some cases, networks decide enough is enough. In others, their leverage accomplishes the near-impossible — in Luhrmann’s case, $120 million in production money and a season released in two parts, one on Friday and one sometime next year. Luhrmann managed to knock Netflix off its previously ironclad commitment to the all-at-once drop, a commitment so strong that the company’s chief content officer, Ted Sarandos, once swore that if Matthew Weiner, creator of the most acclaimed television series of all time, chose to fight against the binge model, “He would lose.” But Baz Luhrmann won.

Think about that for a second: Baz Luhrmann broke Netflix.

If You Want to Make a Movie, Just Make a Movie: Woody Allen, ‘Crisis in Six Scenes’

Amazon is the ultimate in nouveau riche media: Thanks to its massive primary business and disregard for profit margins, nobody has deeper pockets, and nobody — not Netflix, not HBO, not anyone — flexes harder with its checkbook. Just look at its film distribution arm, which came out of the gate with nothing less than Spike Lee’s best movie in a decade. So it makes sense that Amazon landed the publicity triumph of bringing the ultimate American auteur into TV — and not just that, but TV on the internet.

The problem is that no one seems less enthused by Woody Allen’s first-ever television project than … Woody Allen. Amazon finally announced Crisis in Six Scenes at this month’s Television Critics Association press tour, marking a full 20 months between the show’s initial announcement in January 2015 and its premiere this September. Since then, Allen’s given alarmingly candid interviews like this one, where he admits that he doesn’t watch television, doesn’t know what a streaming service is, and that he’s “regretted every second” since accepting Amazon’s offer of doing “anything you want” for “a lot of money.”

Performative neuroticism from Woody Allen is as newsworthy as Taylor Swift adding another human accessory to her Instagram jewel box, but Crisis’ development feels like the apotheosis of a very specific pattern. Amazon desperately wants the prestige and press of a working relationship with Woody Allen, both as a filmmaker and a first-time TV maker. So Amazon promises all the funds and creative freedom necessary to secure his involvement. And then Allen finds himself not knowing what to do with that creative freedom, because even without Luhrmann’s budget allergy, filmmakers can find television as much of a narrative challenge as a logistical one. From that same Deadline interview: “I had the cocky confidence, well, I’ll do it like I do a movie…it’ll be a movie in six parts. Turns out, it’s not.”

And for all that agonizing, Amazon will emerge with six half-hour episodes — given the title and Allen’s public ambivalence, likely the only six Crisis will ever get. Which adds up to about three hours of Allen written-and-directed material. Which sounds suspiciously like … a movie.

Buy a Calendar: Whit Stillman, ‘The Cosmopolitans’

Amazon’s had a similarly awkward experience with The Cosmopolitans, Whit Stillman’s project about hyperverbal, lackadaisical rich people in a European capital (i.e., a Whit Stillman project). The pilot, starring Chloë Sevigny and Adam Brody, hit the streaming service nearly two years ago, where it remains for fans to watch and absentmindedly wonder what happened. This might be the ultimate drawback of Amazon’s open-pilot system: While the average person knows little about a protracted development process beyond a handful of headlines and the occasional leaked pilot, Cosmopolitans viewers have the evidence right in front of them.

As with Allen, Amazon is Stillman’s film distributor as well as his television network, acquiring the North American rights to Love & Friendship before its Sundance premiere in January. But the multiplatform creative relationship that collaboration was meant to lock in hasn’t panned out. Stillman described the still-ongoing process to Collider as follows, emphasis mine:

“I’m figuring it out as I go along, hold please” is, to put it mildly, not how television works. Compared to a typical series schedule, the idea of simply letting Stillman work at his own pace with barely an outline in place is nuts. Two years in, Amazon apparently still doesn’t have enough material to even put in a formal series order, let alone commence production. Amazon seems to have the patience to wait it out, but the gap between the TV-as-usual introduction The Cosmopolitans got — as one pilot among many — and the path it’s actually taken is only getting wider. And you can bet Hand of God and Red Oaks weren’t given the same chance to go at their own pace.

Know When to Walk Away: David Fincher, ‘Utopia’ and ‘Video Synchronicity’

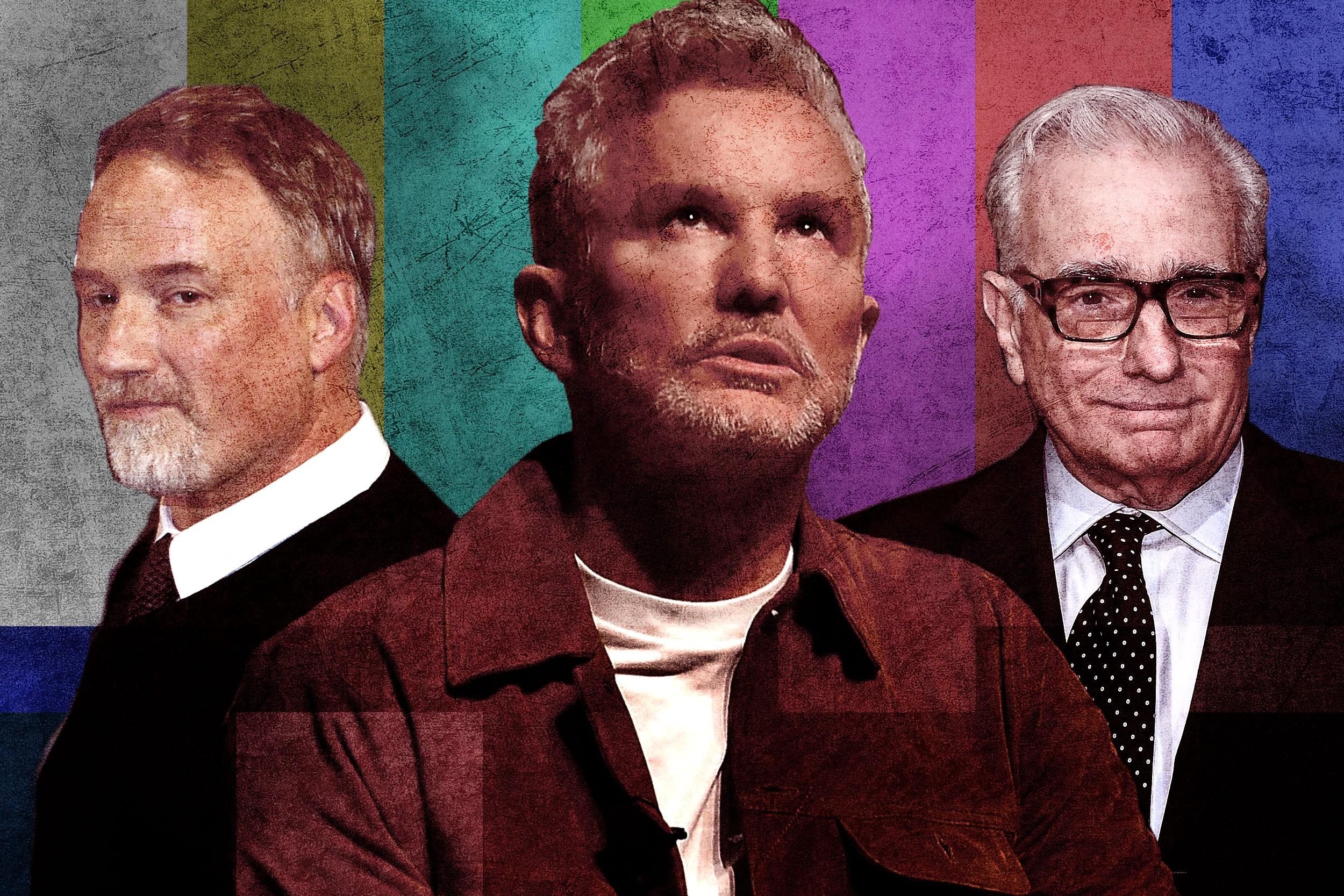

Yes, David Fincher directed the pilot, and still serves as an executive producer, for House of Cards, the series that planted Netflix’s (upside-down) flag and continues to rake in Emmy nominations four seasons into its run (and several seasons past its prime) — a model fellow superstar Martin Scorsese established with Boardwalk Empire in 2010 and repeated, albeit with less acclaim, with Vinyl earlier this year. But since Fincher passed the series to showrunner Beau Willimon shortly after Cards’ debut in 2013, Fincher’s had four distinct high-profile follow-ups in the works, with only one of them showing any sign of coming to pass in the foreseeable future.

Three of those projects are with HBO: the “music video comedy” Video Synchronicity, which Indiewire declared “beyond dead” last summer; the James Ellroy noir Shakedown, which has stayed suspiciously quiet since news broke of its development in 2014; and Utopia, the Rooney Mara–led, Gillian Flynn–helmed British adaptation that officially shut down last August. Only Netflix’s Mindhunter seems to be in good shape, though it has the advantage of precedent: Like House of Cards, it has a prominent star-producer (Charlize Theron) and playwright-turned-screenwriter (Joe Penhall) set to take over after Fincher moves on.

We don’t have the full story behind all three of the stalled/MIA/axed HBO series, but the reports on Utopia indicate almost identical problems to The Get Down: a director infamous for running over already-substantial feature budgets crashing headfirst into television’s tighter funds. Deadline reported that the director and the channel “were not able to reach a compromise on the size of the budget”; IndieWire put Fincher’s ask at a spit take–inducing $100 million, higher than any of his last three features. At that price, the fight is as much symbolic as it is monetary: Fincher’s desire to realize his vision as he sees fit versus a network’s need to put some checks on it.

Like Netflix, HBO found that a filmmaker unused to television was as much a financial challenge as it was a publicity boon. Unlike Netflix, HBO ultimately decided the nine-figure investment wasn’t worth it.

Work Tirelessly: Steven Soderbergh, ‘The Knick’

Amid all these delays, plug-pullings, and unnecessary expenditures, Big Director Television has a lone unambiguous success story: The Knick, Cinemax’s Steven Soderbergh–directed medical drama currently on hiatus after a second-season cliff-hanger. But Soderbergh is unique; even late in his career, he’s still toggling between glitzy, star-studded fare like the Ocean’s trilogy and stripped-down affairs like Magic Mike (which, believe it or not, had a budget of just $7 million. You don’t need big bucks when you have Channing Tatum’s abs!).

Essentially, Soderbergh’s never stopped operating in the lean-’n’-mean mode necessary to make television happen on schedule. He’s also facilitated The Girlfriend Experience, which offers a more widely applicable model for the film-television crossover: importing auteurs from low-budget independent film, which operates under limits on funding and shooting time similar to TV’s. It’s given us Transparent, headed by Jill Soloway with occasional assists from the likes of Marielle Heller and Andrea Arnold, and the first season of True Detective.

It’s not as flashy or attention-grabbing as landing a Great White Director. But it may be something more important: sustainable.