Less than a year ago, Rich Hill was pitching for the Long Island Ducks. Now, the 36-year-old lefty is one of the best pitchers in baseball. He did it, in part, by copying a pitcher eight years his junior.

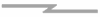

“A lot of people look at Clayton Kershaw and say, ‘Well, he’s got a great fastball. He must throw a lot of fastballs.’ That wasn’t necessarily true,” Hill said. “He throws more like 45 percent breaking balls every time he goes out there. That was a scenario where I could look at that in my own game, where I have a very good curveball — one of the best curveballs in baseball — and you want to use that to your advantage.”

Tucked in there at the very end — “I have a very good curveball” — is the closest you’ll come to hearing Hill express any self-satisfaction. But he’s right — take it from Astros shortstop Carlos Correa.

“He throws different types of curveball — one fast, one slow, and he drops down sometimes to throw one that’s like a slider,” Correa said the day after going 0-for-2 with a walk against the Oakland left-hander. “And his fastball has some hop. Sometimes you get caught in between. You don’t want to be late for the fastball, but you don’t want to get fooled by the curveball.”

Hill’s fastball doesn’t look all that hoppy. According to Brooks Baseball, it averages 91.43 miles per hour, which isn’t anything special even for a left-hander, and it doesn’t have some insane cutter action that makes it hard to square up. Yet, PITCHf/x data shows that Hill throws curveballs more frequently than any other starter, and that’s what gives the four-seamer its hop.

“He throws so many curveballs that when he throws his fastball it looks way faster,” Correa said.

Hill’s journey to the top involves more than Kershaw and the way his fastball and curveball play off of each other. He took a circuitous route that might explain why he doesn’t seem to be enjoying it much.

“I don’t see any satisfaction after the game,” Hill said. “I don’t sit there and look back and say, ‘I’m going to enjoy this,’ because if you do, that’s where you get caught up in trying to overindulge in success. Success isn’t permanent.”

Hill came up with the Chicago Cubs for a cup of coffee in 2005, and as Kerry Wood and Mark Prior went off to the glue factory, Hill and Carlos Zambrano were among those who attempted to pick up the slack. In his mid-20s, Hill was a promising midrotation starter, posting a 111 ERA+ in 99.1 innings in 2006 and a 118 ERA+ in 195 innings in 2007. But then it all fell apart.

Back and leg injuries dogged Hill throughout 2008, then he had shoulder surgery in 2009. In 2011, at the age of 31, Hill went in for Tommy John surgery. Along the way he tried to reinvent himself as a sidearming lefty bullpen specialist, but he struggled to throw strikes and ultimately landed in independent ball in mid-2015.

After that 195-inning season in 2007, Hill threw a total of 182 MLB innings over the next eight seasons combined.

All that pales in comparison to Hill’s greatest personal loss, the death of his nearly 2-month-old son, Brooks, in February 2014. Hill, who is married and has another son who was born in 2011, as he prepared for camp with the Red Sox, didn’t catch on with the team and went down to Triple-A. He was sold to the Angels in July of that year, but lasted only eight days there, making two big league appearances without retiring a batter. He had a very brief stint with the Yankees, throwing 5.1 innings for the team, before landing back on the free-agent market that fall.

Hill said he never considered quitting at any point, though many of his contemporaries who battled injuries and command issues did. Instead, he said the years in the wilderness taught him how to recognize what was actually within his control.

“Understanding that was something that takes time for me, and is a learning process over the course of time,” Hill said. “Knowing that time is a valuable commodity, that it’s something we can never replace, you want to take advantage of the time that we have, every single outing, every single day, every single offseason.”

Last year, at age 35, Hill was pitching for Boston’s Triple-A affiliate in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, when he found himself talking to former big-league pitcher Brian Bannister, who now works in the Red Sox front office. It was Bannister who told Hill how heavily Kershaw relies on his breaking pitches. In fact, Kershaw has used his fastball less and less as his career has gone on.

Bannister said Kershaw, with his curveball, and Zack Greinke, with his changeup, add and subtract from their out pitches to throw them faster or slower, or alter their movement. Hill started to change his finger pressure, grip, arm speed, release point, arm angle, and leg drive from pitch to pitch, expanding a traditional four-pitch mix — fastball, slider, curveball, changeup — into something that looks like a dozen or more distinct offerings.

“I think that there were a lot of things that I was able to take out of that conversation and implement in my own game that made a ton of sense to me,” Hill said.

The conversation with Bannister might have been the lightbulb moment, but the adjustment wasn’t quite that simple. Tweaking a pitch with your lower body takes incredible athleticism and body control, and because of that, Hill renewed his focus on conditioning.

“It’s really a lot of feel, being able to control your whole body,” Hill said. “And that takes time … because that comes from strength. You have to be strong to be able to control your body in that area.”

Along the way, Hill had also moved over from the first-base side of the rubber to the third-base side, which kept the ball in the strike zone more and slashed his walk rate from the teens to 4.7 percent last year and 9 percent this year.

Pitching is like selling real estate, in that the most important thing is location, but it’s also like warfare, in that it’s based on deception. When Boston called him up last September, Hill was leaner, smarter, more experienced, and able to locate and deceive as well as anyone in the American League. With the Red Sox out of the playoff race, Hill reeled off four incredible starts, striking out 36 and walking five, while allowing just 14 hits and five earned runs over 29 innings. He parlayed that stretch into a one-year, $6 million contract with Oakland this past offseason.

Since arriving in Oakland, Hill’s proved that last September’s breakout was no fluke. Despite missing a month with a groin injury and having his first scheduled start after the All-Star break pushed back due to a blister, Hill is 9–3 with a 2.25 ERA and a 28.9 percent strikeout rate. He’s one of the top starting pitchers on the trade market, the kind of player who could swing a pennant race.

The story almost seems too simple: struggle to stay healthy and pitch effectively for almost a decade, get in better shape, have one conversation with a former big-league pitcher, and suddenly turn into one of the best pitchers in baseball at an age when most ballplayers are thinking about hanging it up. It brings up an obvious question: If Hill can do it, why can’t everyone else?

“I just know that for me it’s 100 percent the effort,” Hill said. “You can’t substitute effort. You can’t substitute the will to continue to go out there and fight. … As for other players, honestly I can’t speak toward what happens. Time, injury, other things get in the way — I don’t know.”

Hill’s story seems remarkable, as he’s succeeded in spite of his age, but maybe it’s all finally come together because of it.

“You can’t sit there and tell a 22-year-old kid who comes into the big leagues,” Hill said. “Maybe you can say, ‘I wish somebody had said that to me when I was your age,’ and hopefully that might resonate. But I really don’t think that anybody can learn from too much advice. … You have to learn from failure, and that is the only way you can get experience.”

By that measure, Hill has worlds of experience. He’s chased his dream up to and past the point where he ought to have given up, and after landing with his ninth major league organization, he’s just now reaping the benefits. His one-year contract with Oakland — a throwaway deal for a small-payroll team — has roughly doubled his career earnings and finally given Hill long-term financial stability. Not only that, he’s in line for another, even bigger payday in free agency this coming offseason.

I asked Hill if he’d thought about what his late-career renaissance meant for his family, and he said, “No, I can’t.”

Not “I won’t” or “I don’t want to,” but “I can’t.” The choice of words fits with Hill’s focus on whatever task he’s performing in the moment. Hill doesn’t come across as anhedonic — he’ll joke around with teammates and, from time to time, pump his fist or hop off the mound after a successful inning — so much as ascetic. It’s as if losing that focus, even for a second, could be the end of everything he’s accomplished.

That’s the thing about dreams — you can wake up at any moment.