In the Internet Age, monoculture is unachievable. But there remain a few things that we can all agree on. The Ringer is looking at this rarefied group all week. These are our Undeniables.

The iconography is simple. The palette is spare: bright vermillion fills the oblong bottle, kelly green caps the top — a multi-tiered nozzle that resembles a monastery spire. With some imagination, it can resemble a fresh-picked red jalapeno, or a neon temple whose walls are inscribed with welcomes in five different languages, a rooster perched on top. Before sriracha became a universal sauce, it had universal aspirations. David Tran, founder of Huy Fong Foods, which produces the most popular sriracha sauce in the world, recalled a moment early in his venture’s infancy that crystallized his vision for the company’s future. "After I came to America, after I came to Los Angeles, I remember seeing Heinz 57 ketchup and thinking: ‘The 1984 Olympics are coming. How about I come up with a Tran 84, something I can sell to everyone?’"

America’s fascination with Tran’s sauce — a blunt interplay of heat, pungence, and the comforting salve of sweetness — had largely grown through word of mouth heading into the 21st century. Sriracha’s appeal was forged in late-night noodle shops and college dorms. Even when its presence isn’t made explicit, it’s been everywhere all along (see almost any preposterously cheap spicy tuna roll ordered at happy hour).

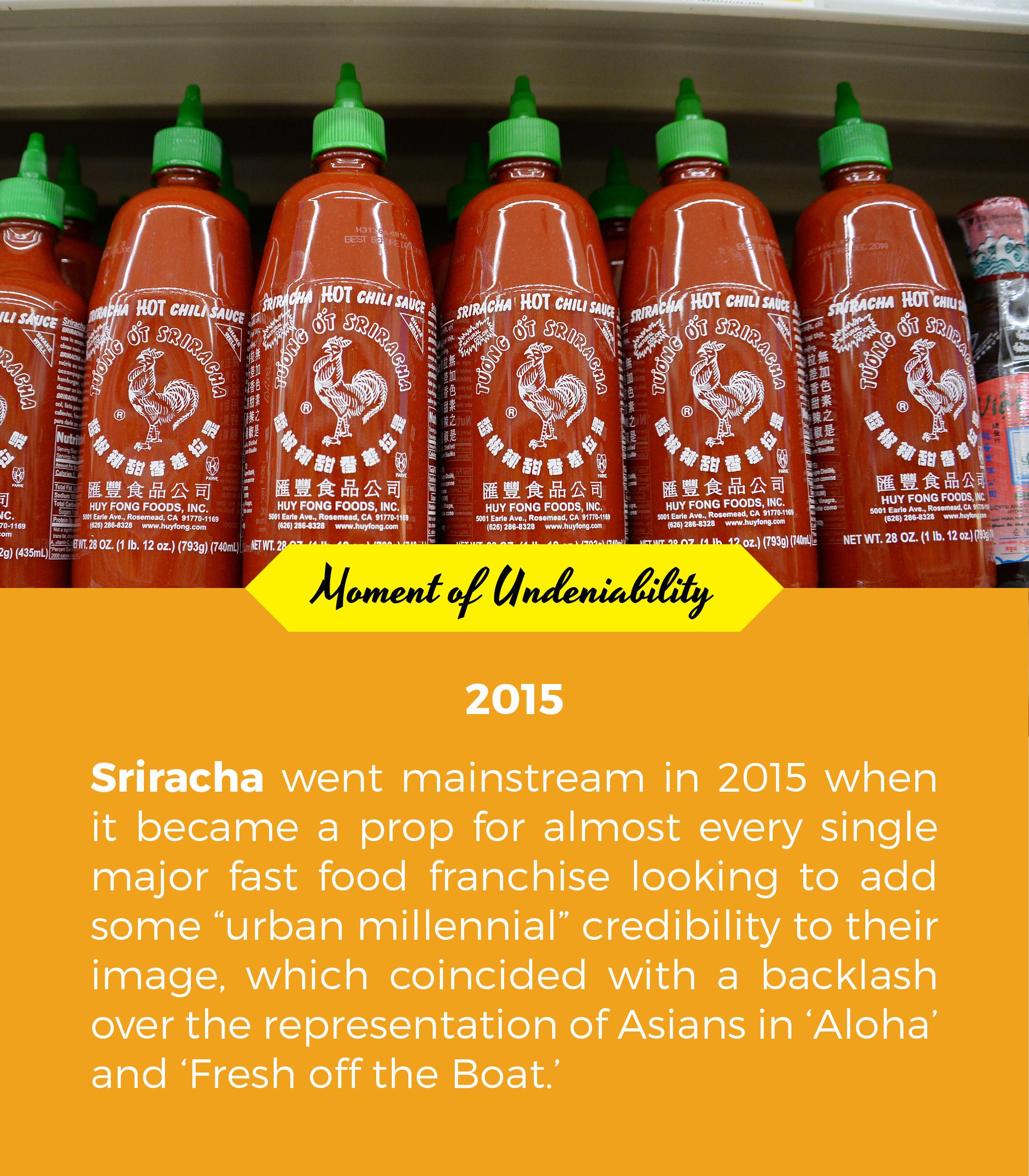

National establishments had begun harnessing the power of sriracha’s growing allure as early as 2000, when P.F. Chang’s began using it, but it wouldn’t become a full-on fast-food trend until 2015, when the industry co-opted sriracha’s cult appeal and turned it into a siren song for fast food’s target demographic: hipster stoners.

In 2015, you could apply a sriracha honey drizzle to your Pizza Hut pizzas. That was the year Denny’s added a sriracha spicy chicken sandwich to their menu and Applebee’s introduced a new sriracha shrimp dish. Two blocks from my house, Shakey’s Pizza Parlor advertised a sriracha chicken pizza; two blocks from my friend’s house, Circle K promoted their sriracha chicken taquitos.

Taco Bell released a bizarre 30-second ode to obsessives that doubled as a promotion for the Sriracha Quesarito, an ad that featured modern urbanites who make wedding dresses out of Taco Bell sauce packets and are willing to shave "SRIRACHA" into their heads. The commercial makes strong use of imagery, but outside of the word constantly appearing on the screen in one form or another, sriracha is treated as an idea best understood through color association — there are reds and greens all over, but the iconic bottles never make an appearance. That is, of course, because Taco Bell isn’t using David Tran’s product — none of these brands are.

Here’s the thing about sriracha: it’s not Sriracha. Tran holds no trademark over its name, only its logo and bottle design. Companies are free to vulture the name recognition while reengineering the sauce to fit their intended purpose. Therein lies its undeniability: David Tran’s exact sriracha recipe may not be available to the public, but with only six core ingredients (red jalapenos, garlic, distilled vinegar, sugar, salt, and xanthan gum), it’s as open source as any name-brand foodstuff available on the market. But no matter how good or bad an outside interpretation, the signifiers always lead you back to the source, to the first time you let the rooster into your life.

Sriracha takes its name from Si Racha, a coastal town in Thailand, but you won’t find many green-topped sriracha bottles lining Thai restaurants. Tran created his version of sriracha to be used as a dipping sauce for pho, but it won’t be found at any pho restaurants in Ho Chi Minh City, either. Sriracha, or at least what we popularly know as sriracha, is quintessentially American, in birthplace and in spirit. It is a constantly replenishing artifact of founder David Tran’s immigrant story, one that articulates a placelessness both literal and metaphorical.

After the fall of Saigon, the Communist Vietnamese government began disenfranchising the large ethnic Chinese community within its borders, of which, Tran and his ancestry — which had moved in the late 19th century to Saigon from the city of Chaozhou in the Guangdong province of China — belonged. The diaspora was given second-class citizen status, and in 1976, was forced out of Saigon’s metropolitan area and into uninhabited rural lands as a way of stifling political dissent. The only way out was through bribing officials and ship captains with gold to gain entry into dilapidated freighters destined for other lands; in other words, to become human cargo.

In late December 1978, Tran boarded the Huey Fong, a Taiwanese ship that took him and more than 3,000 other refugees into Hong Kong waters. As an adult boarding the ship, it cost him 12 taels of gold, the equivalent of $3,000 in that year. The freighter was en route to Taiwan, but there weren’t enough resources on board to accommodate the sheer amount of people. The ship anchored in Hong Kong, but no one was allowed to disembark because the Huey Fong had broken maritime rules by eschewing its port of call. Once Taiwan also disavowed the ship, the refugees were stuck in limbo amid an increasingly dire health situation. The standoff would last nearly a month before Hong Kong officials allowed the passengers to land. Police searched the Huey Fong after it had been cleared and discovered $6.5 million in gold within the ship’s engine room. "It was later discovered that the ship’s logs were forged and that the whole operation had been launched with Vietnamese cooperation," a 1980 Christian Science Monitor report stated.

After a month at sea without proper ventilation and with little food or water, Tran spent another six months in abeyance waiting for the U.N. Refugee Agency to process his case. He was one of at least 840,000 Vietnamese "boat people" to have successfully fled the country since 1978, according to the U.N. He landed in Los Angeles in January 1980 and started his business a month later with what was left of his savings. It would be named Huy Fong Foods (the "e" was dropped intentionally; "Huy" is a common Vietnamese given name). Tran has said he named his company after the freighter because it would be easy for him to remember. How could he forget?

In 2015, Jack in the Box aired a TV spot promoting a new spicy sriracha burger. It curiously decided to play up how difficult sriracha is to say, and how foreign it is to the American palate: "And the best part is, it’s not just sriracha sauce, it’s creamy srir — " The narrator slurs intentionally. "Whatever it’s called. It’s awesome sauce." That year, sriracha found its new place in the food industry as a kind of cultural shorthand for low-stakes adventurism available to the discerning, open-minded fast-food patron, and, in the wrong hands, became something that could only truly be considered "awesome" through whitewashing. Taco Bell used sriracha as a symbol of cult appeal. Jack in the Box took sriracha at face value, mocked it, then claimed to have made it better by turning it into something else.

Tran was urged to make his sauce less spicy in Huy Fong’s early days. Change it to a tomato base, people told him, so that the sauce would reach a wider audience. "Hot sauce must be hot. If you don’t like it hot, use less," Tran said. "We don’t make mayonnaise here."

The Jack in the Box commercial stepped into a cultural landscape increasingly embattled by the concept of authenticity and the unflattering realities of Asian representation. Cameron Crowe’s Aloha was under fire for having Emma Stone portray a Hawaiian with a Chinese last name. Chef and author Eddie Huang penned an aggrieved letter to distance himself from the ABC sitcom Fresh off the Boat based off his memoir because it had altered his family story beyond recognition. We were witnessing a moment of sriracha mayo-fication, and maybe it wouldn’t have been so troubling if it wasn’t made clear how easily history can be wiped away.

Of course, it’s more complicated than that, and all of this applies to sriracha, too. Huy Fong sriracha is an American product that reinterprets a traditionally Thai sauce and was created by an ethnically Chinese man born and raised in Vietnam. It is not an "authentic" representation of what is served with seafood in Si Racha, but it is authentic to Tran, a former South Vietnamese army major who made chili sauces with his family to pay for their way out of Communist rule. Authenticity, like nostalgia, is rooted in origin stories that don’t necessarily exist. It’s a word I’ve largely eliminated from my lexicon, because it attempts to wrangle things as complicated and fluid as tradition and experience into a binary of acceptable or unacceptable. The company name, the rooster insignia that marks Tran’s Chinese zodiac sign, the time spent formulating the recipe in the months spent waiting for asylum to be granted — sriracha is an incredibly personal document of trauma. The "rich man’s sauce at a poor man’s price" was made for all, but none more than David Tran himself. It doesn’t get any more authentic.

From 1996 until 2010, Huy Fong Foods made its headquarters a 170,000-plus-square-foot facility in Rosemead, California, about a half-mile from where I live. I remember the air around there, oversaturated with the stinging redolence of chilies, garlic, and vinegar. After the company was sued in 2013 by the city of Irwindale for creating a public nuisance at its new facility, Tran himself opened the factory up for tours to jokingly prove that Huy Fong Foods wasn’t producing tear gas. It’s an assaultive odor, to be sure, but you don’t get to decide how involuntary memories affect you.

I was raised in a Vietnamese household that was particularly chili-obsessed. We had a row of Thai bird’s eye chili plants in our backyard; growing up, I delighted in their ripening process, transforming from lime green to aubergine to bright red. When there was a surplus, we’d make our own chili garlic pastes. At the dinner table during every meal, my dad had a can of Budweiser and a Thai chili to nibble throughout the meal. As a child, watching my dad eat bird’s eye chilies without any sign of faltering was my idea of heroism. I’d get there eventually, but sriracha was my training wheels. In my earliest memories, it was always resting in the side door of the refrigerator, the green-capped bottle was always there at the Vietnamese restaurants my family frequented. Before its presence spanned the globe, sriracha was everywhere in the small world I inhabited. A few feet from the former production facility, I awkwardly planted my first kiss.

The air around there? It smelled like home.

The old Huy Fong Foods headquarters sits at the end of a shallow cul-de-sac, adjacent to a railroad currently under renovation to provide an underground corridor for more expedient transit. The industrial building was once home to the Wham-O company that created the Frisbee and the hula hoop — postwar American relics that had, in another time, taken the country by storm. The facility, in its varying iterations, had always been a wellspring of generational Americana.