Lenny Dykstra threw his book party at a strip club. “It wasn’t crazy, actually,” the 53-year-old former outfielder demurs. “We just took a few pictures with some of the girls there—that’s it.” Maybe that’s all it was: a clever photo op, a canny understanding of the Dykstra brand. His new memoir, House of Nails, is raunchy and profane, all money and girls and even a little bit of baseball, covering Dykstra’s boom years with the Mets and Phillies. It’s all extremely 1993. Lenny is, too: He spent the morning of his book release on the air with Howard Stern, whisper-cracking jokes about his penis (Darryl Strawberry’s, too).

So the strip-club shindig is of a piece with the story Dykstra is selling. But most book parties don’t happen at strip clubs, I suggest. I’ve thrown Lenny a 2–0 fastball, and I can see his response coming before he gives it. “I’m not most people,” he croaks. We’re speaking on the phone, but it sure sounds like he’s smiling.

House of Nails (subtitled The Construction, the Demolition, the Resurrection) is about what you’d expect: a celebrity-stuffed tell-all, a brand-burnisher, an inside look at a story its subject claims has never been accurately told. The beginning and middle are well-established: Dykstra entered the big leagues with the Mets in 1985 as a wispy 5-foot-10 spark plug. “When I showed up,” he says, “they thought I was the batboy. I shouted to the guy, ‘I’m Lenny Dykstra, and I’m the best fucking player you got here!’” Outlandish, yes, but not completely wrong. He won a World Series with the team the next year, platooning in the outfield with Mookie Wilson and endearing himself to fans with a penchant for clutch hits and up-to-11 intensity. They called him Nails.

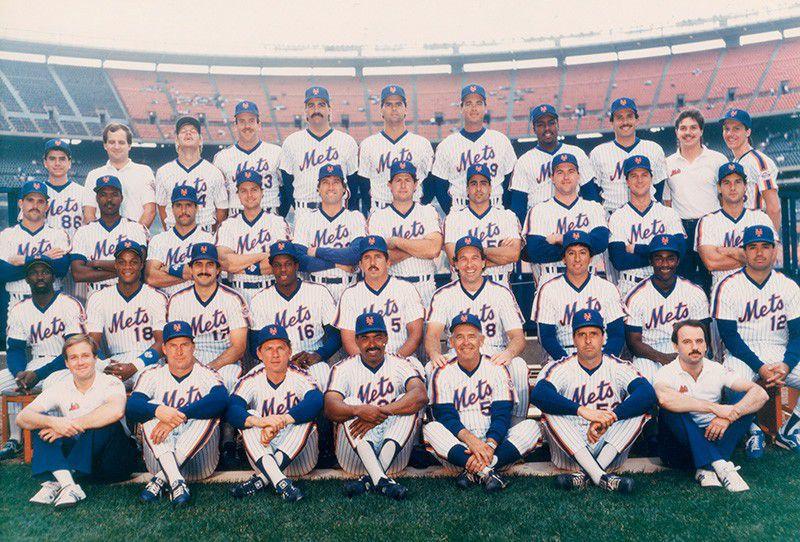

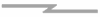

Those 1986 Mets — Doc and Darryl and Kid and Keith and Ron and Nails — ran roughshod over the league (108–54!) in that magical season, laughing at their opponents the whole time. Probably mooned them, too. That’s just who they were, equal parts urbane and reckless. New Yorkers were flattered to see something of themselves — their finer qualities, but also their vices — in their heroes. Doc Gooden and Darryl Strawberry stunned, and then spiralled. Keith Hernandez and Ron Darling settled into the city, becoming neighbors and narrators and gym buddies to millions. Dykstra was the loudmouth with a jaw full of dip. His future was easier to predict.

Except it wasn’t. Dykstra was traded to Philadelphia in 1989, and his years there were marked by the same balls-out style, only somehow kicked into an even higher gear. Dykstra began using steroids (he writes that he learned about Deca Durabolin at the public library in Jackson, Mississippi), turning himself into a three-time All-Star. Off the field, Nails was Nails: he went big (Major League Baseball sent him to Europe as a goodwill ambassador in 1993, a decision I’m sure MLB regretted immediately), and he went home (drunk, in 1991, he wrapped his Mercedes-Benz around two trees — a site that is now, Lenny points out, a “famous landmark”).

Somewhere along the way, he became improbably wealthy, even for a professional athlete. He bought and operated car washes, and was hand-picked by Mad Money host Jim Cramer to make stock market picks. (House of Nails suggests you sign up for stock tips at nailsinvestments.com.) Dykstra was on top of the world: he bought a jet, and then the house Wayne Gretzky built in Thousand Oaks, California. Or as he says, “I made more money than God, swimming in pussy, the whole deal.”

And then it all came crashing down: Dykstra lost the Gretzky mansion in 2010, and was convicted of bankruptcy fraud two years later. He spent six months in federal prison in Victorville, California — what he calls “the big hotel the federal government puts you in for free.”

House of Nails is a relatively unsparing chronicle of it all, the excess and the mess. Dykstra was present for more than one nadir of American culture (the baseball steroids crisis, the cocaine ’80s, the market crash of 2008), and he’s here to bear witness. He’s also here to brag about it.

As mea culpa, the book is a failure. Dykstra apologizes, over and again, to his infinitely patient wife, his children, all the while not quite seeming to know why exactly he’s apologizing. But as pure, weapons-grade gossip? The book is a no-holds-barred success. Dykstra’s wingman is Jack Nicholson. Dykstra’s cocaine buddy is Mickey Rourke. Dykstra’s close personal friend is Charlie Sheen; when he learned that Sheen was HIV-positive, Dykstra sent Sheen a bracing, heartfelt email — subject line: “PRIVATE AND CONFIDENTIAL” — suggesting Sheen go public with the news. We know this because Dykstra prints it, in full, in House of Nails.

And through it all, there’s Dykstra’s peculiar voice: proud, boastful, occasionally remorseful. At every turn he seems compelled to remind the reader how hard he’s had it, and how intensely he’s succeeded. How “badass” Düsseldorf was. How stylish the Kangol driver’s cap he insisted on wearing to dinner in Paris was. How much blow he did in Amsterdam.

Dykstra is an aging athlete who’s suffered financial troubles; it’s not exactly a surprise that he produced a book that leverages both his successes and his failures. But the way he goes about it, marked by twin desires to confess his sins and to remind the reader how fucking cool those sins were, suggests a bone-deep ambivalence about the whole enterprise.

Maybe Dykstra wrote the book because he wanted publicity. Maybe he needed a paycheck. Maybe he wrote it to justify starting his bawdy Twitter account, or to furnish it with material. All he will say is that he felt like he had to, and had to do it hard. It’s just what he does.

That much becomes clear in our time on the phone. Dykstra is bleedingly, strikingly human, a jumble of hurts and slights and boasts and occasional real gestures toward redemption. He murmurs, he snaps, he whispers. What sound like a gang of large cast-iron pans clang multiple times while we speak. It’s a little sad, and a little hopeful. It’s darkly funny. Lenny’s going to tell his story. He hopes we like it.

We were so right for our time,” Ron Darling says. He’s reflecting back on those ’86 Mets, the championship season now 30 years in the rearview. “We were gritty, a little nasty, dirty. And that’s exactly how the city was then.” Darling, who pitched 13 seasons in the majors, sounds wistful, measured — and still, three decades later, a bit excited. “I think that’s why it resonates so much for a certain fan of a certain age. They thought they were kind of tough and gritty, and the team they loved was the same.”

If Dykstra feels that he has to play the beyond-the-pale ex-jock, his cerebral former teammate has taken a different approach. What if, Darling asks, that guy on the field isn’t gritty? What if, instead, he’s riddled with anxiety?

It’s this gap — between an athlete’s on- and off-field persona, between the pitcher on the bump and everyone else — that makes Darling’s new book, Game 7, 1986, so fascinating. The book zooms in on Darling’s start in the deciding game of that year’s World Series against the Red Sox, and runs inning by inning, through the worst 3.2 frames of his career.

The game itself is easy to forget: In the same way the U.S. Olympic hockey team still had to beat Finland after stunning the Soviets with the Miracle on Ice, you’d be forgiven for assuming that the ’86 Series ended after Mookie’s grounder trickled through first baseman Bill Buckner’s legs in Game 6. Instead, the Mets lost a day to rain, and then played another nail-biter, a come-from-behind 8–5 win. Darling’s book is a testament to the fallibility of sports memory, of our need to remember things as we felt them.

Darling does the unthinkable for the ex-athlete: he corrects the record. Here, that means dwelling on his flaws, and in exactly the way Dykstra won’t. “I think if I had been more in the moment — let’s-not-think-through-this-too-long — I would have been a better player,” he says. But this is the hand he’s been dealt, and he’s playing it.

Darling has written a book about his biggest failure, the one that’s haunted him for three decades now. He reproduces his pitching line throughout, as sort of a scarlet letter: 3.2 innings, three earned runs, six hits, one walk, no strikeouts. No decision. Eventually, though, that line becomes a badge of honor. Darling choked in the biggest game of his career, he tells us. Yet here he is.

And even though the Mets won that game, Darling is still thinking about what it means to lose, to have lost. “We just watched LeBron James have one of the greatest moments you could ever have,” Darling says. “But all I could think about [was]: What are the Warriors thinking? What are their fans doing? How could they even relate? I’m much more interested in that. Even though I’m so happy for LeBron, I’m interested in what Steph Curry is doing, like I was doing two days after the parade. Sitting in their apartment or house when their wives and kids are gone, and they’re by themselves, and they have to look at themselves and say, ‘Well, what the hell happened?’” Darling insists he’s been asking that question for the last 30 years.

If you ask Darling, he’ll tell you that he had a middling career. He never won much of anything. He spent too much time in his head to be a killer on the field. He — as did all of those Mets — cared too much about Manhattan nightlife.

All this, of course, is bullshit. Darling pitched one of the greatest collegiate games of all time, transitioned from the Ivy League to the bigs, won a hundred-plus games and a ring, worked his way into the hearts of three or four generations of Mets fans. And if you keep pressing, he’ll acknowledge his extreme modesty: “I know that I was a good player — I was a solid player. But I was different than how I was portrayed. I probably played a part in a lot of that, but really, I was a Worcester, Massachusetts, blue-collar guy who took the ball every fifth day. Not the Yale-educated, GQ-cover kind of guy.”

And maybe, Darling suggests, the thing that crippled him as a pitcher is exactly what makes him part of the best broadcast team in baseball. Maybe it’s what makes him such a compelling writer.

For Darling, writing is like pitching — slow, difficult, solitary — only it’s, well, fun. Or at least less miserable. “What’s better about this is that it’s not in the moment,” he says. “I can take my time. There’s not 55,000 people who are gonna boo me if I pick the wrong word. Maybe the end result is that I should have been in an individual sport, rather than a team sport. That might have been better for me.”

It might be better not to be your heroes, Darling suggests. Not everybody can run as hot as Nails did (and does). Failure takes a toll, especially if you’re paying attention. This is pitching, as Darling experienced it: “If you don’t do your job well, the ball that’s been given to you is taken out of your hands by your boss and given to someone else because they don’t trust you with it. And as you walk off, a walk of shame in front of 55,000 people — you know what? You weren’t good enough today.”

But it was awesome to be me, bro, Dykstra counters. He takes us back to a time when this was acceptable, when our athletes could gallivant like buffoons and be celebrated for it. It’s hard to argue with him: It was awesome to be Lenny Dykstra.

Times change. When Dykstra answers my call, he’s on another line — another phone entirely — speaking to a bank representative, trying to get some credit cards to work. “This is part of our interview, bro,” he says. “I need to activate these cards.”

“I can help you with that,” the female voice on Dykstra’s speakerphone chimes in. “They’re both black — the black cards, of course,” he says, wanting to make clear that they’re ultra-exclusive American Express Centurions. It’s hard to tell if he’s performing for me, or for himself, or just slipping back to a time when Dykstra was on top of the fucking world, bro.

But there’s a hiccup: “No, I’m off a little bit — they’re actually ATM debit cards,” he says, either to me or to the bank rep. Maybe to both of us.

I tell Lenny I’ll call him back in five minutes. When I do, he’s still on the other line.