What’s the best way to present an interactive story? Four decades into the video game age, there’s still no clear-cut answer. The debate is at the center of the game-making world. Until recently, designers and academics couldn’t agree on whether a narrative structure was even necessary. Games could be the next frontier of storytelling. Or not. As game designer and author Greg Costikyan once wrote, “Story is the antithesis of game.”

Two recently released titles with similar gameplay conceits, Quantum Break (Remedy Entertainment/Microsoft Studios) and Superhot (Superhot Team), approach narrative in different ways, with differing results. They’re both fun to play, but Quantum Break runs afoul of an ancient storytelling maxim: Show, don’t tell.

Quantum Break, a big-budget Xbox exclusive from the studio that created the Max Payneseries, unfolds traditionally. The protagonist, Jack (Shawn Ashmore, best known for playing Iceman in various X-Men movies), and the antagonist, Paul (Aidan Gillen, a.k.a. Littlefinger), deliver their dialogue via cut scenes — noninteractive story dumps that cover the what, where, how, and why of the game’s world. Meanwhile, expository information is available through text files and email threads that the player can access via computers scattered around the game world. The problem is that these methods take the player out of the action. That’s a bummer, because the powers that Quantum Break puts at your command are a blast to use. Jack and Paul (both characters are playable) can freeze time. Enemies turn into statues and bullets hang in midair. I found myself wanting to restart fight scenes just so I could use these powers over and over again. Unfortunately, because the characters are part of a tightly scripted narrative, that’s impossible. It’s as if Quantum Break puts you in control of a Ferrari — Jack and Paul can sprint at hyperspeed just like the Flash — only to make you read emails while sitting in traffic.

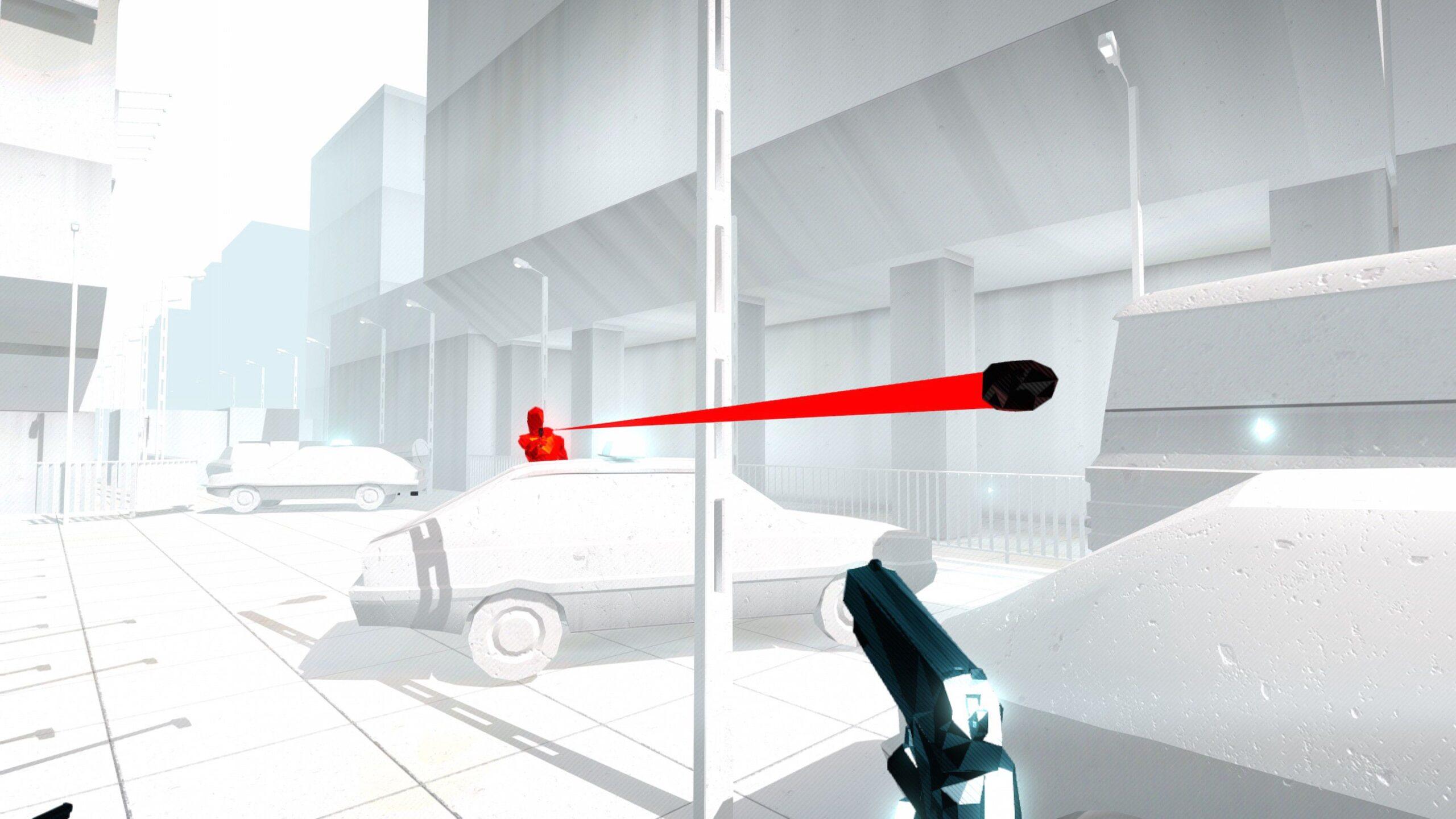

Superhot takes a minimalist approach to story — so minimal that I’m not sure there even is one. The graphics are basic, backgrounds are white on white, and enemies are rendered in almost wireframe simplicity. The lack of a narrative is winked at throughout, with the game’s meta-protagonist complaining: “It’s kind of random. No plot, no reason for anything. Just killing red guys.” Fair, but the gameplay mechanic is simple and addictive: Time moves only when the player moves. The result is fluid, nonstop action, unburdened by plot. It’s John Wick minus all the talking.

Great video games find a way to balance a player’s agency with the scripted moments that, by necessity, negate the interactivity that makes games unique. Quantum Break feels like a product stuck between worlds: more interactive than a movie, but not interactive enough to be a truly immersive game. Superhot’s stripped-down gameplay is a reminder that, in video games, sometimes it’s better to shut up and kill red guys.

This piece originally appeared in the April 13, 2016, edition of the Ringer newsletter.