Will Smith has been so many things to so many people. I mean that sentimentally and philosophically, yes, because he’s been making music and movies for nearly three decades now. But really I mean it literally. Even a small sampling of Smith’s movies offers up a very large number of versions of Will Smith. For example, since Collateral Beauty, his new movie that opens Friday, is a holiday movie (let’s say we’re defining that as “a movie that is released within two weeks of Christmas”), let’s look at those.

Will Smith has six holiday movies in his filmography: Ali (2001), The Pursuit of Happyness (2005), I Am Legend (2007), Seven Pounds (2008), Concussion (2015), and now Collateral Beauty (2016). If we arrange them into groups based on the intentions of each film, we have two I Am A Serious Actor, Take Me Seriously movies (Ali, Concussion), one I Am A Serious Actor But Also Let’s Not Forget How Good I Am At Movie Crying movie (The Pursuit of Happyness), one There Are Actual Monsters In This But Don’t Worry I’m Excellent In It movie (I Am Legend), one Let’s Get Philosophical movie (Collateral Beauty), and one Let’s Get Philosophical And Also Let’s Have Me Die In A Really Bizarre Way movie (Seven Pounds, suicide by jellyfish). That’s a remarkable range.

For comparison, let’s look at holiday movies from Denzel Washington and Leonardo DiCaprio, two movie stars who are of equal or greater star power. Here’s Denzel: The Pelican Brief (1993), The Preacher’s Wife (1996), The Hurricane (1999), Antwone Fisher (2002), The Great Debaters (2007), Fences (2016).

And here’s Leo: What’s Eating Gilbert Grape (1993), Titanic (1997), Catch Me If You Can (2002), Gangs of New York (2002), The Aviator (2004), Blood Diamond (2006), Revolutionary Road (2008), Django Unchained (2012), The Wolf of Wall Street (2013), and The Revenant (2015).

You know what I see on the Denzel and Leo lists? Several very good movies. You know what I don’t see? Not one single zombie, and not one single jellyfish.

Everything I’ve read so far about Collateral Beauty has described it as a different kind of bad. In Rolling Stone’s review, Peter Travers used the phrase “stupid, sentimental swill,” so that’s pretty bad. Evan Saathoff, writing for Birth Movies Death, called it “an offensive disaster,” which is also bad. Groucho Reviews called it “Chicken Poop for the Soul,” and at first I thought that was pretty clever, but then I Googled “chicken poop for the soul” and it turns out there are actual books called that, so that made the review less clever, but it did not make its assessment of the movie any less bad. I read all of those, and then I read some more, and then I read some more, and they all leaned in that same direction. And YET, here I sit, Friday, December 16, 2016, husband and father and son, excited and ready to pay to watch Collateral Beauty. And it’s all because of only one reason: Willard Carroll Smith Jr.

I can’t believe his name is actually Willard.

Q: What are the most interesting versions of Will Smith?

A: There are seven that qualify.

The Perfectly Measured Cool Will Smith

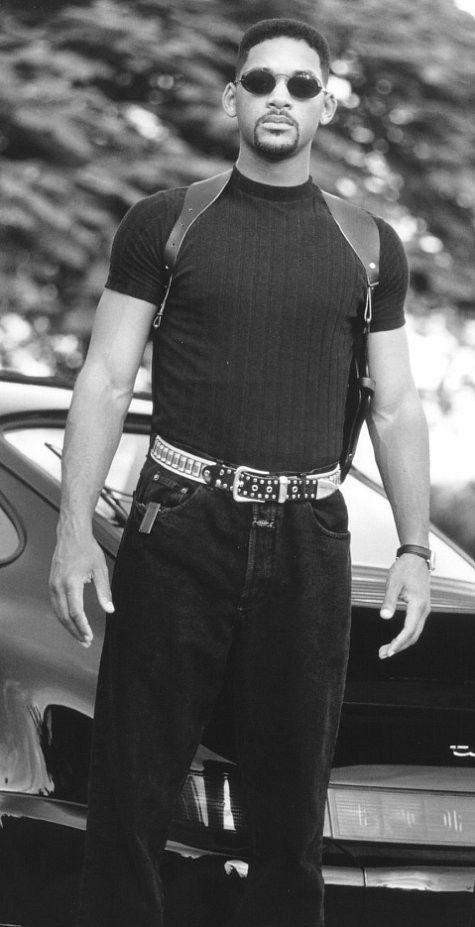

He’s done this a couple of times, in a couple of different ways. The very best example, though, is his Detective Mike Lowrey from the Bad Boys franchise. As Lowrey, Smith takes his innate, wholesome charm he’s so good at cultivating and adds in juuuuuuuust enough edge so that it doesn’t sound weird when he cusses but not so much edge that he becomes intimidating or overwhelming. It remains one of the great feats of his career, because pulling off that trick — creating a brand of cool that’s accessible but also enviable — is very, very hard to do.

Think on it like this: There are three main branches of cool. There’s the cool where you’re cool in an understated way; a sort of Fuck Being Cool cool. There’s the cool where you’re cool in a way that suggests you’ve put a little bit of effort (but not a grating amount) into your coolness. And there’s the cool where you’re cool in a way that is so far past what normal humans can do that it basically becomes useless because no one else can copy it. A good example of the first one would be, say, Russell Crowe in Gladiator. A good example of the last one would be Brad Pitt in Fight Club. And a good example of the middle one, which is the hardest to hit, is Will Smith’s Mike Lowrey.

Take this perfect Mike Lowrey scene: In the first Bad Boys, Lowrey and his partner, Martin Lawrence’s Marcus, are in a gym getting harangued by Joe Pantoliano’s Captain Howard as he shoots brick after brick at the rim. After Howard finishes yelling and dismisses the two, Lowrey takes a second to make a comment to imply that he sleeps with a lot of women to Marcus, then he picks up a basketball off the floor, swishes a 20-footer as a flummoxed Howard looks on, then says to both, “Everybody wants to be like Mike,” then leaves. And he does so while wearing a gun and a slim-fitting black T-shirt that accentuates his muscles.

The Has an Accent Will Smith

Muhammad Ali in Ali. Cypher Raige in After Earth. Bennet Omalu in Concussion. It’s always an adventure.

The Quietly Broken Will Smith

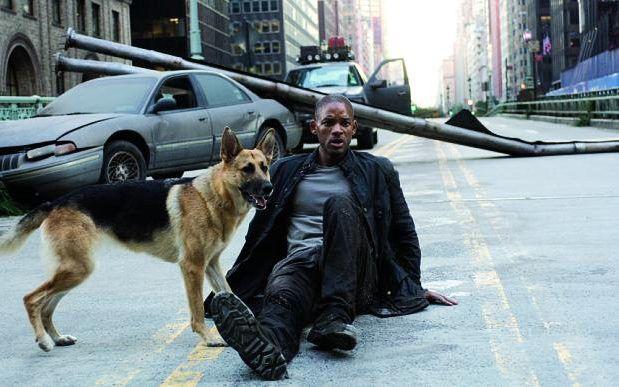

This is my personal favorite version of Will Smith. He was quietly broken for most of Hancock (a movie that is wildly silly if you think about it for more than, like, 15 seconds), where he played a lovelorn superhero. And he was quietly broken for, like, 40 percent of The Pursuit of Happyness. But the movie where he was quietly broken for all basically all of it and just was absolutely superb in that capacity: I Am Legend.

In I Am Legend, Smith plays Robert Neville, a genius scientist who finds himself swallowed up whole by a combination of loneliness (a plague turns nearly all of the world’s population to zombies; he goes something like three years without seeing another human) and aching sadness (his wife and child were killed in a helicopter crash during an attempted evacuation).

He sets up mannequins throughout the city so that when he goes out during his day trips (the zombies are only active at night) he can pretend to talk to them, and it seems like a sweet thing, but then he has a breakdown after [REDACTED] happens, and so then he tearfully begs one of the mannequins to say hello to him. It’s brutal. It’s exactly the right amount of pain, and he lets it build so perfectly. It’s an elite Will Smith scene. Here, watch:

I remember being all the way overwhelmed at that part when I saw it in the theater. It’s wonderful how much of a powerhouse he can be in moments like that.

(Semi-related: There’s a part in San Andreas where the Rock is supposed to have this very emotional moment where he talks about his daughter dying. The whole time I was watching, I was thinking, “Man, I really wish it was Will Smith giving this monologue right now.” Directors should be allowed to sub in actors in certain situations like pinch hitters in baseball. Imagine Will Smith giving every My Child Died monologue in every movie. That’s some 2001 Shaq shit.)

The Hopeful/Actualized Will Smith

Above, I mentioned that Smith is Quietly Broken for 40 percent of The Pursuit of Happyness. In the remaining 60 percent of the movie, he transitions from The Hopeful Version of Will Smith to the The Actualized Version of Will Smith. It’s the second-best version of him. He holds those almond eyes open just a little longer than normal, focuses them in on something, allows for the light to grow in them, and it’s a wrap, my dude. He barely even has to say words. He just summons that good energy into his chest like some sort of very lovable nuclear reactor. This is him doing it at the end of The Pursuit of Happyness, when the bosses at the firm he’s been interning at tell him he’s won the job they were offering:

One thing that I need to happen: I need to be struck down and buried in the earth before Will Smith. I don’t think I’d be able to see that news, or read that news, or hear that news. It’d be too hard.

The Empty Will Smith

Cypher Raige from After Earth. SMH. Cypher Raige is like if they made a list of all the things Will Smith is good at doing as an actor, showed it to him, then said, “Look, don’t do any of this while we’re filming this movie.”

To be clear: This is not a good version of Will Smith, it’s just an interesting version of Will Smith, same as how a picture of a broken bone isn’t good but it’s still interesting.

The Only Cool to Middle-Aged Men Will Smith

Bang. That’s exactly what he was as Nicky in Focus, a movie about swindlers and hustlers and con artists, but really a movie about Will Smith in a suit saying things like, “I can convince anyone of anything,” and “This is a game of focus,” and “Attention is like a spotlight, and our job is to dance in the darkness.” Focus was the first time in Will Smith’s career that he was proactively marketed to audiences as being a cool guy, which is the type of thing you do when you’re targeting middle-aged men.

Accuracy In Movie Gambling Sidebar: The best scene in Focus involves Nicky elaborately conning a guy into losing a little over a million dollars on a prop bet during a football game. It’s neat to watch happen because at first it looks like Nicky is unraveling and then at the end of it he explains how he was able to trick the guy (scenes in which someone explains how they tricked someone else are always fun to watch). The only problem, though, is that it actually makes zero sense.

It all starts because Nicky and his date, Jess (played by Margot Robbie), are making little $1 and $10 bets on things happening at the game. Their mark, an ultra rich gambler named Liyuan, overhears them and inserts himself into the betting.

Liyuan and Nicky bet $1,000 on which team they think is going to draw the next penalty. Nicky wins the bet. (Nicky is now up $1,000.) Liyuan ups the next bet to $5,000, and he wins that one. (Nicky is now down $4,000.) Nicky proposes they double-or-nothing it, which means if Liyuan wins then he will get another $5,000 and if Nicky wins he will get back the $5,000 he just lost. Nicky loses. (Nicky is now down $9,000.) They bet $50,000 on the next play. Nicky loses. (Nicky is now down $59,000.) They bet $100,000 on the next play. Nicky loses. (Nicky is now down $159,000.) Nicky, his hooks all the way in, proposes they draw high card from a deck of cards for $1.1 million, which is Nicky’s remaining money. Liyuan agrees. Nicky loses. (Nicky is now down $1,259,000.) Nicky, pretending to be frustrated, says to “double it,” meaning the $1.1 million bet. That’s where it gets tricky.

Earlier, Nicky and Liyuan double-or-nothing’ed the $5,000 bet, and later Nicky proposes another double-or-nothing bet, so him saying “double it” here would imply that this would just be another double-or-nothing thing. That means that when Nicky wins it (which he does), he just wins back the original $1.1 million that he’d just lost. And that means Nicky is still at a net loss of $159,000 when their gambling session ends, even though he and Jess celebrate like they’ve just won a lot of money. And even if the “double it” meant the entire pot, that still means Nicky and Jess walk out of there having won $0, despite having gone through a whole lot of trouble to trick Liyuan into making a bet. I don’t know. That does not seem like sound financial planning, not even for a con man.

The Oscar-Worthy Will Smith

The most transcendent, most overpowering, most everlasting scene of Will Smith’s acting career is the “How Come He Don’t Want Me, Man?” scene from the episode of The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air where his dad abandons him again (Season 4, Episode 24). There’s no arguing that. There’s no trendy pick against it. There’s nothing except acceptance. That’s the one you pull up when you want to show the full force of Smith’s ability to tug on all the empathetic and sympathetic parts of you. That’s the one where he did it better than he’s ever done it before.

HOWEVER. If you want a single scene that allows for all of the best parts of Will Smith to be put on display, a different one gets the call. It’s the scene from Fresh Prince where he’s in the hospital after he got shot (he and Carlton were robbed at an ATM and the robber shot at them when Carlton reached for his wallet). You get the full Will Smith spectrum there. He goes from funny to curious to disbelief to exasperated back to funny again to angry to compassionate to Angry to ANGRY to heartbroken to overwhelmed. It’s brilliant, really, that he’s able to skate through all those feelings so quickly and effectively.

This one is the most dynamic version of Will Smith.

This one is the first-best version of Will Smith.