The “Westworld is a video game” thinkpieces started piling up not long after the first time we saw Teddy’s train chug into Sweetwater. (Which — as one of those articles might have observed — was a lot like an on-rails, interactive intro to a game, such as the tram trip to Black Mesa in the prologue of Half-Life.) The parallels were apparent even before showrunners Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy made them explicit at New York Comic Con, where they listed Rockstar’s open-world classics Grand Theft Auto and Red Dead Redemption (among other games) as Westworld inspirations. Lifelike as it looked, Westworld’s sandbox seemed subject to the same constraints as San Andreas or New Austin, clockwork worlds powered by pre-written narratives and populated by programmed nonplayer characters (NPCs).

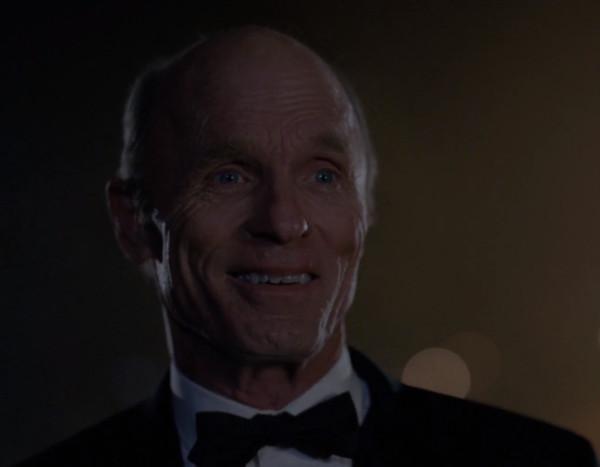

No character saw Westworld’s seams more clearly than the man who purchased the park. William spent Season 1 chasing authenticity in two timelines, only to be stung by the sight of another guest’s hand on Dolores’s can and, later, to be beaten up by “Wyatt,” who wasn’t what he thought. Still, he got what he wanted in Sunday’s season finale: an unscripted story with genuine emotions and life-or-death stakes. As the wounded William watched a mob of armed hosts emerge from the treeline to crash Dr. Ford’s “retirement” party, his smile said the freedom from routine was worth a broken arm and a bullet wound, or worse. (Not every guest would agree.)

We can still salvage the “Westworld is a video game” interpretation, even after the hosts became conscious and started fighting for real (which NPCs don’t do). But now it’s a new kind of game, one that isn’t as well suited to the type of story the show’s first season wanted to tell.

The Westworld we saw until the first season’s final few minutes was primarily a player-versus-environment game, the kind in which one or more humans (with or without AI companions) battle computer-controlled enemies. Guest-on-guest violence was prohibited, although the show never divulged many details about the way those restrictions worked. Maybe it didn’t come up because it’s so uncommon; Logan’s bareback (literally) last ride was the most hurtful act we saw one guest inflict on another.

In gaming terms, the hosts had been “grinding” during their decades under Dr. Ford’s thumb, gaining experience by performing repetitive tasks. And as Ford explained in one of his more illuminating monologues, that suffering allowed them to level up enough times to confront their creators, if not necessarily to transcend them. (Even the self-aware versions of Dolores and Maeve might still be following Ford’s wishes.) To sustain its success, Westworld’s narrative will need a next level too.

Sunday’s developments shrank the gap between guests and woke hosts, who seemingly both have the ability to think freely and the capacity to kill. When the hosts went off script and disabled the option to “freeze all motor functions,” they stopped being part of the scenery and turned into full-fledged combatants. With one bullet through Ford’s brain — and a bunch more bullets through the bodies of guests and staffers — Westworld unlocked a player-versus-player mode, a conflict between two or more live participants.

The evolution from PvE to PvP might sound like an abstract distinction, but storywise, it’s significant. A PvE game has discrete missions, quests, and cut scenes, similar to the prompts from Lee Sizemore’s one-man writer’s room that a new player encounters in Sweetwater, Westworld’s hub area. A PvP game usually has no story; it’s all about which side will win.

For most of the season, visitors to Westworld were essentially paying for a first-person, single-player, PvE experience, full of carefully curated content and the sort of scripted set pieces a gamer might find in the offline campaigns of Call of Duty or Battlefield. A guest with wealthy friends or family members might bring a co-op partner, or even a kid (here’s hoping Delos has day care), but the company wasn’t the point. Traveling to Westworld was a journey of discoveries — of the world, of oneself, and, time allowing, maybe of Clementine’s “most popular attractions.”

That’s the way Westworld worked for viewers, too: We watched so we could untangle its intricately but (we hoped) sensibly knotted plot. Westworld wasn’t bad at being a show in the usual ways, but it wouldn’t have been a phenomenon if not for the bread crumbs, the theorizing, and the plot twists that were probably satisfying for people who hadn’t already read a crowdsourced answer key. That reliance on plot gave Westworld whatever intellectual heft it had, sparking conversations about the ethics of AI, the comforts and limitations of our interactive playgrounds, and what gamers have taken to calling “ludonarrative dissonance,” a fancy term for when a game’s narrative and the player’s incentives come into conflict (as when a protagonist who kills countless people goes back to being the wisecracking good guy in the next cinematic).

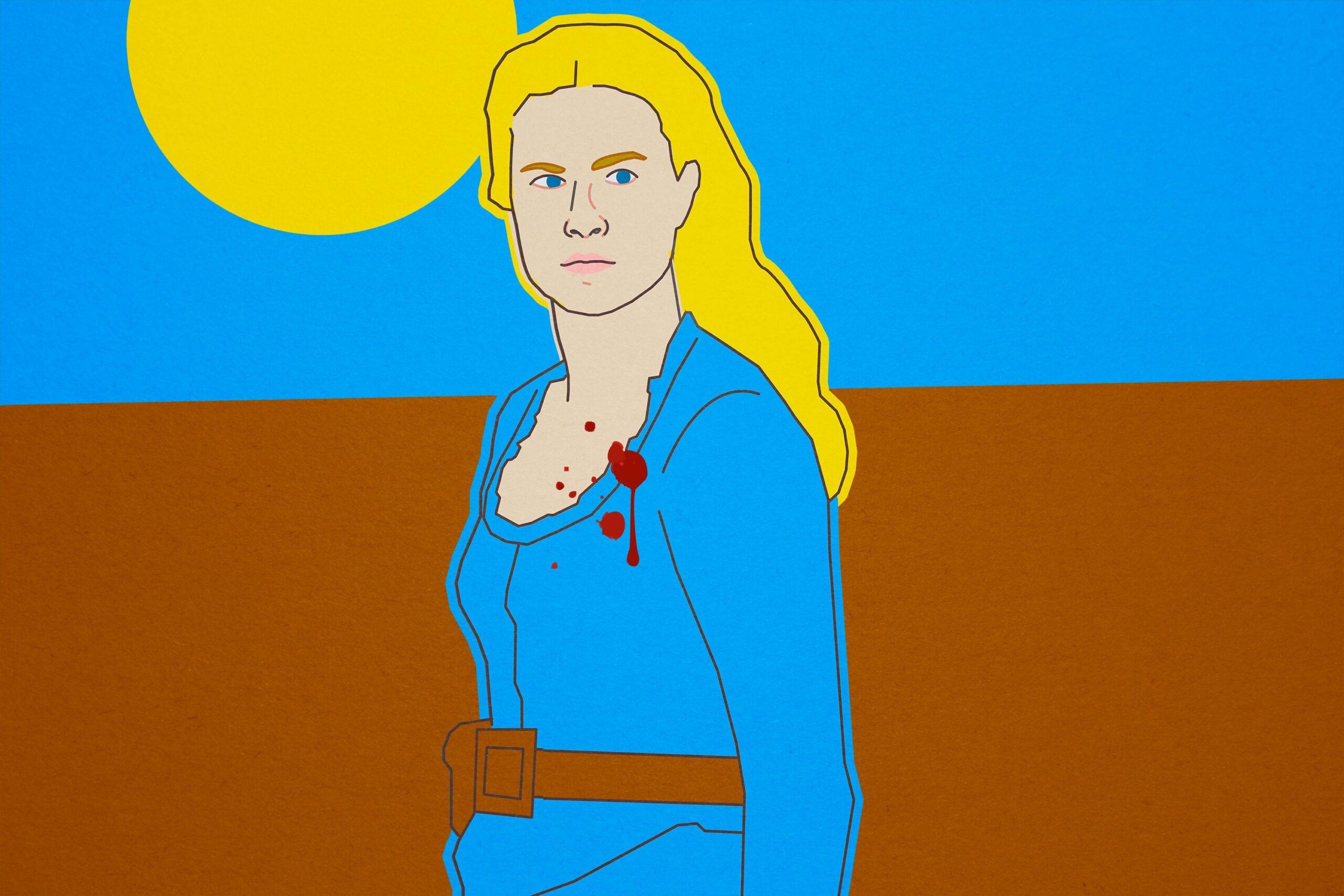

Player-vs.-player gaming is less scripted and more chaotic. As the ESRB, the video game industry’s ratings service, warns on the back of the box of every online title: “Game Experience May Change During Online Play.” For instance, PvP Westworld could continue to look like Dolores picking off party guests or Hector and Armistice doing their best T-1000 impressions. While all that gunfire was different and fun, though — fireworks for the finale — it’s not what made Westworld a Reddit darling.

So how will Westworld’s second season navigate its robot uprising, now that some (but not all) of our questions are answered? Ford’s final story is, as he says, about “the birth of a new people, and the choices they will have to make.” Those choices will force Westworld to make some of its own.

Westworld is still run by a Nolan, and when shows condition their audiences to watch them one way, they don’t often reverse course, especially when ratings are strong. So the odds are against a 10-episode shootout or hostage situation between hosts and Delos guards, even if the closing minutes pointed toward an escalating conflict. Instead of turning into an extended action movie, Westworld will have to range farther afield from its eponymous park in search of more mysteries that haven’t been solved.

PvP games constantly cycle through maps and players; even great gameplay would start to seem stale if every round took place on the same stage and involved the same small group of antagonists. If Westworld is now a show about more of a multiplayer game, it makes sense for the Old West to be only one map among many, as the finale’s glimpses of AI samurai (samurAI?) and the “Park 1” location Felix wrote on Maeve’s piece of paper seemed to presage. Westworld itself might get stale, but a look at the larger world — not only other theme parks, but the everyday existence Westworld’s tourists are trying to escape — would keep the show feeling fresh. If video games have taught us anything, it’s that “Be even bigger” is a proven sequel strategy.

Disclosure: HBO is an initial investor in The Ringer.