The Best Locker Room in the Biz

With Kevin Durant’s arrival in Golden State, the NBA’s gravitational force has officially moved west. Here’s how the media is making hay of Warriors World.Back in October, Connor Letourneau and Anthony Slater, two writers new to the Golden State Warriors beat, were at a preseason practice in Denver. On any other NBA beat, such a practice would amount to a news-less Siberia. But these are the Warriors. There is always news on the Warriors beat.

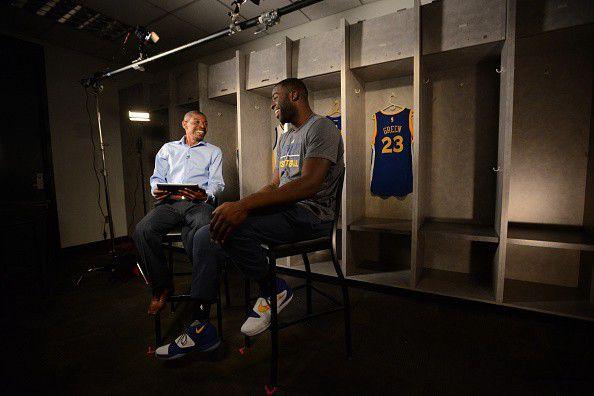

"We were like, ‘Let’s just talk to Draymond,’" said Letourneau, who writes for the San Francisco Chronicle. "Because when you don’t know who else to talk to, you talk to Draymond." After practice, Letourneau and Slater, who writes for the Bay Area News Group, found Draymond Green sitting on a table.

As it happened, Green had heard the Clippers’ Paul Pierce tweaking Kevin Durant for signing with the Warriors. Slater didn’t even have to mention Pierce’s name. Green just started roasting Pierce:

Green had just handed the reporters the perfect NBA story for the age of Twitter. It was raw. It had elder abuse. ("Nobody care what you did" — this to a former NBA champion.) More to the point, Green was saying something wildly interesting that wasn’t particularly important.

"I gave you guys some good quotes, didn’t I?" he told the reporters after the interview. "I want to see that blow up." They reported it. The story blew up.

After two months on the beat, Green’s rant doesn’t seem all that unusual. Letourneau and Slater have since found themselves covering Durant’s divorce from Russell Westbrook; Green’s head-kick of James Harden; and the Warriors’ head coach, Steve Kerr, confessing that he had used pot. When you’re on the Warriors beat, sometimes all you have to do is show up.

On the night before Thanksgiving, I went to Oracle Arena to see what it was like to cover what one writer called the latest "quote-unquote superteam." Before the Warriors played the Lakers, dinner was laid out in the media room. I bore an invitation from Ray Ratto, the longtime San Francisco writer: "Let us gather over a wilted salad and a meal made of neglect and hate."

Ratto and I sat at a table and watched a few dozen media members whirl around us. "This beat, now it’s become a clown car …" Ratto said. "There are people at ESPN who I know. I ask, ‘Are you coming up for the Laker game?’ They said, ‘I’d love to, but we have too many people there.’ It’s Game 15!"

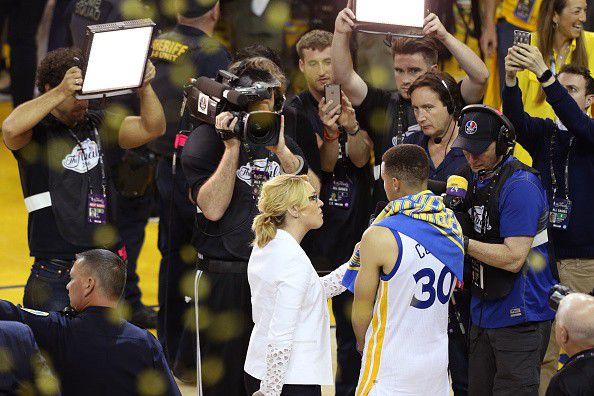

Oakland — not New York or L.A. — is now the basketball media capital of the world. Steph Curry’s corner locker got so crowded after home games that, this season, Curry and the team’s stars conduct postgame interviews behind a podium — a practice teams mostly reserve for the playoffs. The Warriors don’t just see national writers swoop in for the night. They see national writers swoop in and stay. Last season, The New York Times had Scott Cacciola abandon the Knicks and embed with the Warriors. This fall, Tim Bontemps, who covers the NBA for The Washington Post, moved to San Francisco to use Oracle as a forward operating base. "It’s the epicenter of the basketball world …" said Bontemps. "I think it’s even going to be bigger than the Heat were."

Jerry West, a Warriors executive board member, told me the media crush is far larger than the one that congregated around the Kobe-Shaq Lakers of the early 2000s. There is more interest from foreign media, there are more outlets in America, and, thanks to iPhones, every sportswriter is shooting video.

"What’s the fascination?" Ratto asked. "The fascination is people are trying to guess if the Warriors are going to be the next great ratings grabber in American sports. And that’s what the roll of this dice is. That’s why Tim’s out here. That’s why Scott was out here last year."

"ESPN is partially responsible for this," he continued, "because I think they, more than anybody else, invented the notion of the national name that must be covered every day, whether or not they do something. This" — the circus around us — "is now the logical extreme of that."

That any reporter would be trying to get into the Warriors locker room is a great, historic irony. For years, the beat was the lowliest pro beat in the Bay Area outside of maybe the San Jose Sharks. The Warriors’ 12 straight losing seasons (1994 to 2006) meant that their press corps only rarely minted a national star like Ric Bucher. A columnist with an interest in basketball, like the Mercury News’ Tim Kawakami, might drop by. But, otherwise, Kawakami said, "there were a bunch of mediocre players walking around and maybe two or three reporters."

Marcus Thompson, who’s now a columnist at the Bay Area News Group, became a Warriors beat writer in 2004. Five years later, he had what amounted to an exclusive audience with Steph Curry. This was Curry’s rookie season, when he was losing minutes to Acie Law — when he was a basketball player rather than a walking brand. Curry and Thompson carried on a months-long argument about Denzel Washington’s character in the movie The Book of Eli: was he blind or not? When Curry came off the court during a game, he would sometimes look over at Thompson at the press table and wave his hand in front of his eyes.

These days, Warriors players and coaches are known for being unusually media-friendly. This wasn’t always the case. Ethan Strauss, who wrote for the site Warriors World before being hired by ESPN, would ask coach Mark Jackson a question and find it met with a blank stare.

"In many ways, I still associate this building with sadness …" Strauss told me. "Maybe because it’s so sad-looking. The bowels of Oracle are an ugly, gross place. … It’s a uniquely public and tangible reminder of failure that everybody absorbs and has to put a good face on."

Now, on a Wednesday night against a so-so opponent, Ratto and I were sitting in the place every writer wanted to be. As if to prove the point, Strauss and Bontemps walked by. They are young, ambitious, and view the Warriors as the vehicle through which they can make their reputations. They were also wearing suits. "See, that’s objectionable," Ratto said. "It’s a basketball game, not an insurance office."

After a few minutes, Ratto escorted me to Steve Kerr’s pregame press conference. We took seats in the third row. Kerr sat at a podium with his arms crossed. "Hi, Ray," he said.

"Thanks for coming," Ratto said.

Strauss contends there is no such thing as a truly happy beat writer. But, these days, the Warriors beat seems awfully happy by the standards of the trade. Kerr is part of the allure. "He’s the most approachable head coach in sports, probably …" said Letourneau. "You forget that he’s a head coach of an NBA team."

You could see Kerr’s press-charming in action on Thanksgiving eve. Every question put before him, whether about his friendship with old assistant Luke Walton or his favorite Thanksgiving dish, earned the coach’s genuine consideration. Asked a bland question about Shaun Livingston, Kerr explained how Livingston’s role as the offensive catalyst of the Warriors’ second unit had been usurped by Durant. Kerr was offering a lifeline to Livingston, who struggled early in the season, but wasn’t saying anything to get himself in trouble. It was the kind of answer that filled more pages of a reporter’s notebook than the reporter probably expected.

Ask most NBA coaches a rough question and their faces tighten. When Kerr gets a rough question, he uses humor to deflect it. "It’s Psychology 101," said ESPN writer Brian Windhorst, "but it’s very disarming."

Kerr and his old coach, Gregg Popovich, have nearly opposite views of the media, as Kerr once explained to Strauss. Pop’s stint in the military gave him a taste for clandestine operations, whereas Kerr father’s was an academic. "I think that there’s a professorial aspect to Steve where he likes explaining," said Strauss.

This season, Kerr seems willing to explain just about anything. Why he opposed Donald Trump and supported Colin Kaepernick. Why he stumps for gun control. Last Friday, on a podcast with CSN Bay Area’s Monte Poole, Kerr admitted he used marijuana to treat his chronic back pain. The next day, after the beat writers had found themselves with yet another huge, national story, Kerr remarked, "I do find it ironic [that] had I said, ‘I’ve used OxyContin for relief for my back pain,’ it would not have been a headline."

Kerr’s skill with the press lies in his approach. Even though the Warriors have innovated how NBA basketball is played — and, if you believe Joe Lacob, how NBA teams are run — Kerr refuses to act like he invented the pick-and-roll. The approach filters down through the franchise. "You go in and realize, not only is this the best fuckin’ basketball team I’ve seen with my own eyes, they’re the nicest dudes," said Dieter Kurtenbach, who covered the Warriors for KNBR.com and now writes for Fox Sports. "They all took after Kerr."

The other thing Kerr has is quiet self-confidence. This would seem natural for a coach. In fact, few have it when dealing with the media. In a press conference, Kerr, who did two stints on TNT, will say exactly what he wants, and will rarely allow himself to be pinned in a corner by tough questions. When the pregame presser broke up, Ratto told me, "If I had to sum it up, he owns the room by walking into it. But when he leaves it, you don’t feel like you got owned."

For a desirable beat, the Warriors press corps is shockingly young. Strauss is 31 years old. Slater and Letourneau are 26. "I’m the old man," said ESPN.com’s Chris Haynes, who is 34.

Strauss arrived in 2010, when the Warriors weren’t in a position to deny a press pass to anybody, and was hired full-time by ESPN in 2014. He tends to think in meta terms about player dynamics, and even the act of beat writing itself. "He’ll break himself down for 10 minutes," one NBA writer said fondly. Strauss told me that early in his career he asked former head coach Keith Smart about his "predilections." Everyone laughed at him for using such a big word. In a locker room, Strauss said he learned, "you have to modulate your communication."

That’s another big word, I pointed out.

"I know," he said. "Shit."

With Haynes moving from the Cavaliers beat to the Warriors beat this season, Strauss now has time to write longer features, like his piece that portrayed Draymond Green as an NBA hand grenade. When we met, Strauss was still trying to unplug. "You hate the road trips, and then you’re not on them and you worry …" he said. "The process that Marcus has gone through is, I guess, the process I’m going through now."

Marcus Thompson, who was raised in East Oakland, is a spiritual, church-going man. He once said he considered quitting sportswriting because he found it "trivial." The sign of media power in the modern NBA is the "side conversation," a private moment a reporter secures with an athlete after the media scrum has ended. After the Thanksgiving eve press conferences, I saw Thompson talking with Curry in the hallway. He and Curry do this all the time.

"He allows me to see past the brand guy that he puts up …" Thompson said. "I just think it’s hard for him to start that anew with anybody else. It’s too late. He’s Steph now." Curry wasn’t excited when Thompson told him he was writing his biography — one of at least two books that will come out of the Warriors beat. But Curry didn’t try to stop him, and he didn’t roll his eyes when Thompson used press availabilities to fish for biographical material: "Hey, remember when you were in high school …"

Brian Windhorst called Slater "one of the best daily beat writers that’s working in the NBA." There’s a certain symmetry in the compliment: Slater, who covered the Thunder for The Oklahoman, was Windhorsted to Oakland this season, following Durant as Windhorst had once followed LeBron James to Miami.

One of Slater’s specialties is recognizing a newsy answer within interviews and posting the video or transcript snippet to Twitter. In October, Slater and Letourneau were covering Durant and Lacob’s appearance at an awards ceremony at the Stanford business school. The first story that came from the event was Durant’s comment that he hoped the Warriors would lose Game 7 of the Finals so he could sign with them. But thanks to the transcript Slater published, reporters soon dropped that and focused on Durant calling his new team "selfless" — an apparent shot at his old Thunder pals. What Sopan Deb was to Donald Trump, Slater is to the Warriors.

Among the beat writers walks a small, goateed man who offers fist bumps and asks, "You good?" The funny thing is, Raymond Ridder, the team’s VP of communications, actually means it. Ridder is one of the handful of PR men in any sport who thinks his job is to help reporters rather than sabotage them. "He’s one of the few guys who still views what he does as a service job," said Ratto. "As opposed to, ‘I’m here to protect the players and the management from you illegitimate pricks.’"

"All I have to do is email Raymond and say, ‘Steph for 15 minutes,’" said one national NBA reporter. "If I’m willing to get on a plane to Oakland for the day, I’m going to have Steph for 15 minutes. … They’re the anti-Thunder."

If you look at which NBA teams get blasted by the press, Haynes said, "nine times out of 10 you can point to a negative relationship between the PR staff and the media." Where the Cavs’ PR staff often eavesdropped on — and even recorded — Haynes’s interviews with players, he said Ridder and the Warriors let him and the players speak alone.

Ridder came to the Warriors in 1998, when the team was in the middle of its run of a dozen straight losing seasons. To compensate for the awfulness of the product, Ridder plied writers with story ideas and the promise of access.

"Now, the pitches are coming to him," said Diamond Leung, who covered the Warriors for parts of three seasons for the Bay Area News Group. "It’s ‘Can I get Steph for five minutes?’ rather than ‘Can you please do a feature story on Brian Cardinal?’"

Even though he’s the gatekeeper to the biggest story in the NBA, if not pro sports, Ridder is still pitching. Take one episode from October. "I get a call [on] a Sunday evening from Ray," Letourneau said. "He’s like, ‘Hey, do you want to go suit shopping with Damian Jones tomorrow?’"

Jones is a rookie center who tore a pectoral muscle before the draft. Ridder noticed Jones was sitting on the end of the Warriors bench in a warm-up, rather than a suit. This is because Jones didn’t own one.

Acting on Ridder’s tip, Letourneau followed Jones to a men’s couture shop and wrote an article. The other Warriors beat writers congratulated Letourneau on a fine bit of enterprise. "It’s like, I didn’t even think of it," he said. "The media relations guys did."

Walk into a Warriors shootaround — held in a court atop a parking garage in downtown Oakland — and you see a scene that makes NBA writers salivate. To the right, there’s Durant shooting from the top of the key. To the left, coach Bruce Fraser firing passes to Curry in the left corner. What’s more, these stars may actually talk to you. "They’re so easy to be around and so easy to deal with and so generous with their time that it’s a complete home run for the writers to know these guys," said Jerry West.

Draymond Green’s relationship with the press is like his right foot: He may insist it functions haphazardly but it is highly strategic. "Players like Kevin, after saying an inflammatory comment they immediately regret it," said Slater. "Draymond is the opposite. He knows what he’s saying at all times, knows how it will be tweeted, and wants it out like that." Before delivering a memorable 2015 rant about the Clippers’ Dahntay Jones, he told Strauss, "Just watch."

Even when Strauss published his story about Green before the season, there was little blowback. No writer can remember Green responding publicly. And while Strauss said being in the media room these days certainly feels a bit different, he didn’t see any reason he couldn’t ask Green a question.

Steph Curry, Strauss said, is "Derek Jeter–esque." He’ll answer every question but he’ll never say anything remotely risky. On a night like Thanksgiving eve, this trade-off is more or less accepted; when Curry is asked about North Carolina’s "bathroom bill," as he was in March, such opacity gets him into trouble. Still, Windhorst said, "I don’t think there’s a star player in America who is as available as Steph Curry is." When Curry hears a question he doesn’t like, he often says, "That’s funny."

Klay Thompson is the most press-averse of the Warriors’ big four. He grumbles about reporters like men in comic strips grumble about their mothers-in-law. At his postgame presser on Thanksgiving eve, Thompson answered a couple of questions. There was a split-second pause, and he threw up his arm in victory — I’m free! Alas, a reporter asked another question.

Strauss once asked Thompson why, even after a great game, he tried to duck the media give-and-take. Thompson’s head sunk. "I’m not good at it," he said.

Beat writing was once a local concern. Then, in 2010, LeBron James moved to Miami. The four "Heat Index" writers ESPN assigned to the team — mirroring the network’s beat writers in Los Angeles and other places — were reporting not just for Miamians but for the whole country. Windhorst was stunned when Erik Spoelstra’s off-hand remark that his players were "crying" in the locker room after a loss became a national story for ESPN.

There are a few side effects of this treatment of superteams. One is that more writers are fighting for tinier scraps of information. This makes a fetish out of the "side conversation." Or it tempts writers to massage a player’s banal postgame words into news. "The increasing number of media and decreasing nature of the access has created this nether region that none of us are comfortable with and all of us are forced into," said Windhorst, who admitted he’s part of the problem.

Durant’s comments at the Stanford business school made for a great Rorschach test. Durant said this:

Slater and Letourneau didn’t think Durant was taking a sideways shot at Oklahoma City; Strauss said he wasn’t sure. It hardly mattered, because Durant’s words were soon carried back to Russell Westbrook, who said, "We’re going to worry about all the selfish guys we have over here, apparently." Now, it was a story.

Another interesting thing about the Stanford episode is that Durant was saying stuff the reporters would have killed for him to say … in a press conference. This is a further side effect of superteamdom: the good quotes often appear at venues like Stanford, in "branded" interviews for one of the athlete’s sponsors, or in sit-downs with national magazines.

"It makes me wonder if there’s almost this Pavlovian cult of boredom when they’re in the press conference room or in the locker room," Strauss said.

"Pavlovian" is another big word, I pointed out.

"Ah, shit," Strauss said.

The 2010 Heat were villains. The Warriors aren’t, exactly. Indeed, a day after Draymond Green’s right foot connected with James Harden’s face, Green was all yuks: "I didn’t know people in the league office was that smart when it came to your body movements. I’m not sure if they took kinesiology …"

But it’s not just that the Warriors are a bunch of swell guys, Strauss noted. The media has changed since 2010, too. Writers on the NBA beat and elsewhere have been replaced by younger, more liberal counterparts, who have more elbow room to argue what they think. They may not love Durant’s decision to join forces with Curry. But they regard it as something less than an act of treason.

The Warriors beat was so tranquil that the writers initially wondered how Durant would fit in. Early on, when Marcus Thompson asked for a Durant one-on-one, even the industrious Ridder couldn’t produce him. As Thompson told me, "Here was my big worry: that Steph would somehow see that he could be a different way." That is, Durant would do to Curry what Russell Westbrook had done to Durant: offer the blueprint for being a snarling, inaccessible superstar.

But Durant has also shown unexpected moments of vulnerability. In late October, in New Orleans, the beat writers were standing near the sideline as Durant went through his post-practice shooting routine. "They say I ain’t hungry! …" the writers heard Durant yell to himself as he swished 3s from the corner. "They called me a coward!"

Anthony Slater had seen that workout routine many times in Oklahoma City. But he’d never heard Durant’s self-flagellating narration. The fact that Durant was yelling it within earshot of the writers made him wonder if Durant, taking a page from Green’s media strategy, wanted the video to go viral. I want to see that blow up.

"We talked a lot about how much access he’s been giving reporters," said Haynes. "He told me that in OKC he wanted to talk more. But that’s the landscape he came up in and that’s all he knew."

In the Age of Dwindling Access, a superstar who has fulfilled minimal media obligations is said to have "talked." As I watched on Thanksgiving eve, Durant talked to reporters for seven leisurely minutes after morning practice. He talked for another seven after the game. The interviews were friendly and reasonably forthcoming and, most of all, utterly relaxed. "You know what?" said Thompson. "I didn’t see him much at Oklahoma City, but he looks … free."

When the game started, the beat writers took their seats at the top of the lower level. (The Warriors, like every other team, have long since moved writers off the court.) The Warriors started hitting 3s. Curry threw a beautiful pass to Livingston under the basket for a reverse dunk. At halftime, the Warriors had 80 points.

Last year’s Warriors gave their writers a great gift: by chasing the Bulls’ record of 72 wins, they made the NBA regular season meaningful. This year’s Warriors have done something equally interesting: They’ve provided history nearly every night.

Curry hit a record 13 3-pointers against the Pelicans in November — Bleacher Report’s Erik Malinowski came to Oracle figuring to take a night off but wound up writing anyway. Connor Letourneau told me he hadn’t taken a single day off, even on a weekend, since getting on the beat this summer. On Sunday, Haynes got an off day — which meant he only had to write up an interview with the NBA’s Kiki VanDeWeghe, who was calling to say the league wasn’t singling out Draymond Green for special punishment for kicking James Harden.

On Thanksgiving eve, the Warriors broke the team’s 35-year-old record for assists in a game. Kerr and the star players filed through the media room in turn, lingering over their interviews and wishing the reporters a happy Thanksgiving. There was a feeling of a bubble, of a place where greatness and access are meeting for what must be a finite period. "When this little party breaks up," Ray Ratto said, "it will not be replaced by anything remotely as good."