There has never been a point guard quite like Lonzo Ball. The dynamic UCLA freshman has taken the college basketball world by storm in the first month of the season, leading the Bruins to a 9–0 record, including a 97–92 upset of no. 1 Kentucky in Rupp Arena on Saturday. The Bruins aren’t just winning, they are winning with style, averaging 97 points per game and 124 points per 100 possessions (third in the nation) — a seismic leap from an offensive rating of 107 (117th in the nation) last season. Ball is at the center of everything; he has the ball in his hands for most of the game, and he is constantly pushing the pace and creating easy shots for his teammates. You have to have your head on a swivel if you are playing with him.

Ball is leading the NCAA in assists with 9.3 per game, but the numbers don’t really do justice to the type of passer he is. At 6-foot-6 and 190 pounds with a 6-foot-7 wingspan, he has the size to see over the top of the defense, as well as the inventiveness and fearlessness to try any (and every) pass in the book. In this sequence against Texas A&M, he grabs the defensive rebound and throws a full-court outlet pass to a streaking Isaac Hamilton in one motion:

Ball is a bouncy athlete with springs for legs and a tight handle, so he can get anywhere on the court he wants. But while most guards with Ball’s physical tools are looking to score, he is always looking to make the extra pass. He manipulates the defense like a seasoned pro, reading the help-side defender and patiently waiting until he commits before making the dump-off pass:

Even when he has the open shot, or a clear driving lane to the basket, Ball won’t always take it. He’s not a pass-first point guard so much as he is a pass-first, -second, and -third guard.

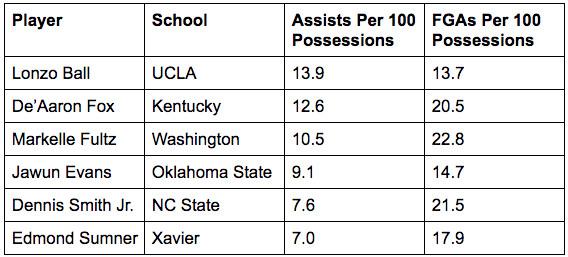

Ball is in a category of his own when it comes to sharing the ball. His per-game numbers are a bit inflated by UCLA’s super-fast pace, but even if you normalize them over 100 possessions, he has significantly more assists (and fewer field goal attempts) than any of the NCAA PGs currently projected to go in the first round by DraftExpress.

Part of the difference in assist rates is due to the composition of each point guard’s respective rosters. Ball and Fox are the top distributors on the list, and it probably isn’t a coincidence that they play with way more talent around them than the others. They make the game easier on their teammates, but their teammates also make the game easier on them. There isn’t as much pressure for them to look for their own shot as there is for guys like Fultz and Smith, who don’t have the benefit of playing with a team full of McDonald’s All Americans.

UCLA in particular is a passer’s paradise. Not only do the Bruins play at one of the fastest paces in the country, but almost every player in their rotation takes and makes 3s at a high volume. The only ones who don’t are their three centers, and Steve Alford rarely plays more than one of them at the same time. Their starting center, junior Thomas Welsh, is a lights-out midrange shooter who is 14-of-14 from the free throw line this season. The Bruins run a five-out offense for most of the game, spreading the defense so far apart they are almost impossible to guard. Kentucky came into its game against UCLA on Saturday with the ninth-rated defense in the country, and it still got shredded, giving up 97 points on 53 percent shooting.

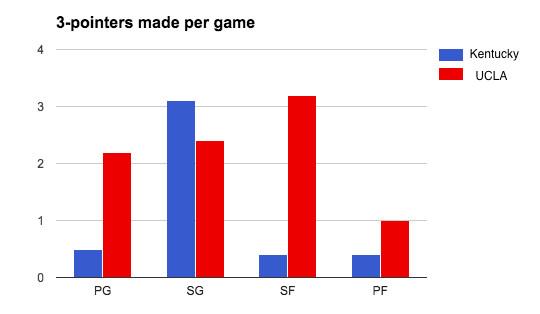

There’s a substantial difference in the amount of spacing provided by the Kentucky and UCLA offenses. In essence, Fox has to work a lot harder for his assists than Ball does. Here is a breakdown of how many 3-pointers each team generates, by position:

Watch the ball swing on this possession from Ball to Aaron Holiday (53.3 percent from 3) to Bryce Alford (41.5 percent from 3) to Isaac Hamilton (45.3 percent from 3). All the pieces fit together perfectly at UCLA, at least on offense.

There’s no player in college basketball more fun to watch go up against overmatched competition than Ball. He’s a 19-year-old who has been given the keys to a high-powered sports car, and he’s allowed to drive it as fast as he wants. With Ball running the show, UCLA starts pouring on the points really quickly and never really stops. He’s a guard who is just as capable of catching an alley-oop as throwing one, and he plays with joy and flair that is contagious:

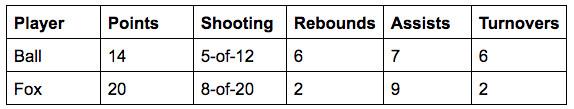

However, for as impressive as UCLA was against Kentucky as a whole, Ball had a very mixed showing going up against a team with the best athletes he’ll likely face all season. The passing windows were much narrower against John Calipari’s team, and the Wildcats were doing everything they could to make Ball beat them as a scorer instead of a passer. He had almost as many turnovers (six) as assists (seven) Saturday, after coming into the game with an assist-to-turnover ratio of more than 4-to-1. You can’t get too cute against players with NBA-caliber size and speed, and you have to take the open shot when the defense gives it to you. And you definitely can’t force a pass that isn’t there:

There’s a lot of Ricky Rubio and Jason Kidd in Ball’s game. What separates him from most pass-first PGs is that he’s also an excellent 3-point shooter. He played a style developed by his father in high school and AAU ball on teams that were essentially the Golden State Warriors on acid. He was given the green light to shoot from anywhere on the floor at any point in the shot clock. The result is a player with unlimited range and no compunction about hoisting from way deep:

As LaVar Ball, his father, told our Danny Chau before the start of Lonzo’s freshman season, “It’s better to shoot a 30-footer with nobody in your face and go through your technique and your form, as opposed to shooting right on the 3-point line with a hand in your face.”

Whether or not that logic holds true for every player, it’s almost certainly the case for Lonzo, who has a bizarre sidewinder shooting motion where he takes the ball up from his chest before releasing it. The closest comparison to his form in the NBA is probably Kevin Martin, a player who was living proof that unconventional shot mechanics can still work. Martin, who retired this offseason after 12 years in the league, was a career 17.4-point-per-game scorer and a 38.4 percent shooter from 3.

The comparison goes only so far, though, as Lonzo needs a lot more room to shoot off the dribble than Martin, and he almost has to take step-backs to create enough space between him and his defender to shoot comfortably. That’s when his absurd shooting range goes from gimmick to necessity. Even when he is well behind the NBA 3-point line, he can still take another step back and fire away.

The problem is that he doesn’t have a lot of other shots in his arsenal. Ball is an all-or-nothing player. Either he is shooting from deep behind the 3-point line or at the rim, or he isn’t shooting at all. He doesn’t have much of a midrange game, nor much of a plan when he’s forced to take a shot from that distance:

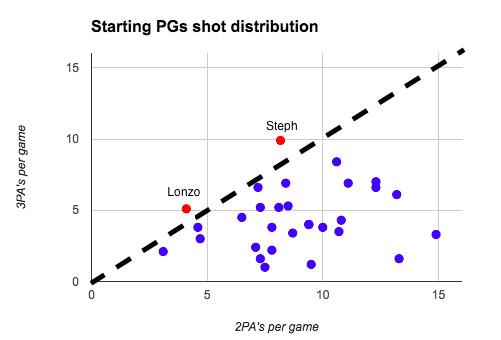

The result is a bizarre hybrid of an offensive player. Whether it’s by choice or necessity, Ball’s offensive game takes the logic of Moreyball to its ultimate conclusion. He takes more 3s per game (5.1) than 2s (4.1), a shot distribution pattern shared by only one starting PG in the NBA:

The difference, of course, is that Steph Curry is a willing 2-point shooter. He just takes so many 3s it’s hard for the ratio of 2s to 3s to equal out. Ball has the shooting profile of a 3-point specialist like Kyle Korver or Anthony Morrow, except he’s also a first-class distributor. As long as he can make 3s at a 40 percent clip, the lack of diversity in his offensive game may not matter. However, if he goes through a shooting slump on the perimeter, he doesn’t have much else to fall back on.

The best way to get him going on offense is to get him matched up with bigger and slower defenders who can’t keep him in front of them on the dribble. The smaller Kentucky guards hounded him into some tough shots Saturday, and he found it easier to score when UCLA went small and moved him all the way to the power forward position. It’s easier for him to get all the way to the rim when going up against 6-foot-8 combo forwards like Texas A&M’s DJ Hogg:

Ball does surprisingly well when matched up with bigger players on defense as well, despite his relatively thin, 190-pound frame. He’s deceptively strong, as he can bench press 270 pounds, and he’s an explosive leaper who knows how to time his jump to make up for his lack of bulk or length:

He got in trouble against Kentucky when he was forced to get into a defensive stance and guard Fox on the perimeter. Ball was hopeless when forced to deal with ball screens, and Fox was doing whatever he wanted against him:

You have to be careful about jumping to too many conclusions based on one game, and Fox and Ball weren’t matched up against each other the entire game. When they were, though, Fox clearly got the better of Ball. It was easier for him to score and initiate the offense against Ball than vice versa. UCLA’s win was more due to brilliant individual performances from TJ Leaf and Aaron Holiday.

Individual defense will be something to watch with Ball all season. He won’t face many more defensive assignments as tough as Fox at the NCAA level, at least until he faces Fultz in Pac-12 play. Those two are the kind of athletes he will have to defend in the NBA, unless he ends up being cross-switched onto bigger players. He’s much better as a team defender, as he has quick hands as well as good instincts about when to reach into passing lanes and generate deflections.

There isn’t a player in the NBA with Ball’s skill set, which makes projecting what he’ll look like at the next level a challenge. His unconventional but effective 3-point shot means he’s not a liability off the ball, but he still needs the ball in his hands as much as possible in order to maximize his game, and he doesn’t have the scoring ability that most elite PGs in the modern NBA have. The spread pick-and-roll doesn’t require great passing instincts. It’s brute-force decision-making, simplifying the offense so that the primary ball handler needs only to be able to make a couple of basic reads in order to create open shots. It’s more important that they threaten the defense as a scorer, which in turn creates opportunities for everyone else on the floor.

Ball is never going to be a big-time scorer, which is the way the point guard position is trending around the league. He would be a great role player on just about any team in the NBA, but building an offense around a player who doesn’t shoot the ball much is difficult in today’s game. There are only nine starting PGs in the league this season who average fewer than 11 shots a game, and only Tony Parker (8.5 attempts per game) plays for a championship contender. The team that drafts Ball, especially if it uses a top-five pick on him, is going to have to bet there’s still a market inefficiency in having an elite passer run its offense when passing the ball has never been easier at the NBA level.