Seattle sees itself as the shining city upon a hill — seven hills, in fact, in a nod to the geography of ancient Rome. There are downtown inclines so steep that the parking decks must be shaped like right triangles. The hills of the northern and southern halves of the city are divided by Lake Union, which must be traversed by bridge (or, if you’re feeling whimsical, by ferry). And from multiple elevated vantage points in the city, you can watch the mass of cars inching slowly down Interstate 5 and feel the nauseating dread that comes when you take in the full scope of a massive highway traffic jam.

As Americans have repopulated cities in recent years, Seattle has undergone especially marked growth. It’s the fourth-fastest-growing city among America’s top 50, according to census data, and it has ranked in the top five each of the past three years. The Seattle region is home to powerful industry — Boeing to the north and south, Microsoft to the east, and Amazon less than a mile from the Space Needle — and there is no end to the city’s growth in sight.

But — and when it comes to city planning, there are always multiple, onerous buts — there simply isn’t enough space to fit all of these people and their cars on the region’s highways. Seattle has the second-worst congestion in America during the evening commute, according to a study by TomTom, second only to Los Angeles. Ask a resident to describe the traffic and you’ll hear phrases like “comparable to Southern California,” or “horrible after 4 p.m.,” or “a giant clusterfuck.” Everyone agrees that traffic is bad, and given the local government’s projections that 800,000 more people will move to the Puget Sound region by 2040, it seems doomed to get worse.

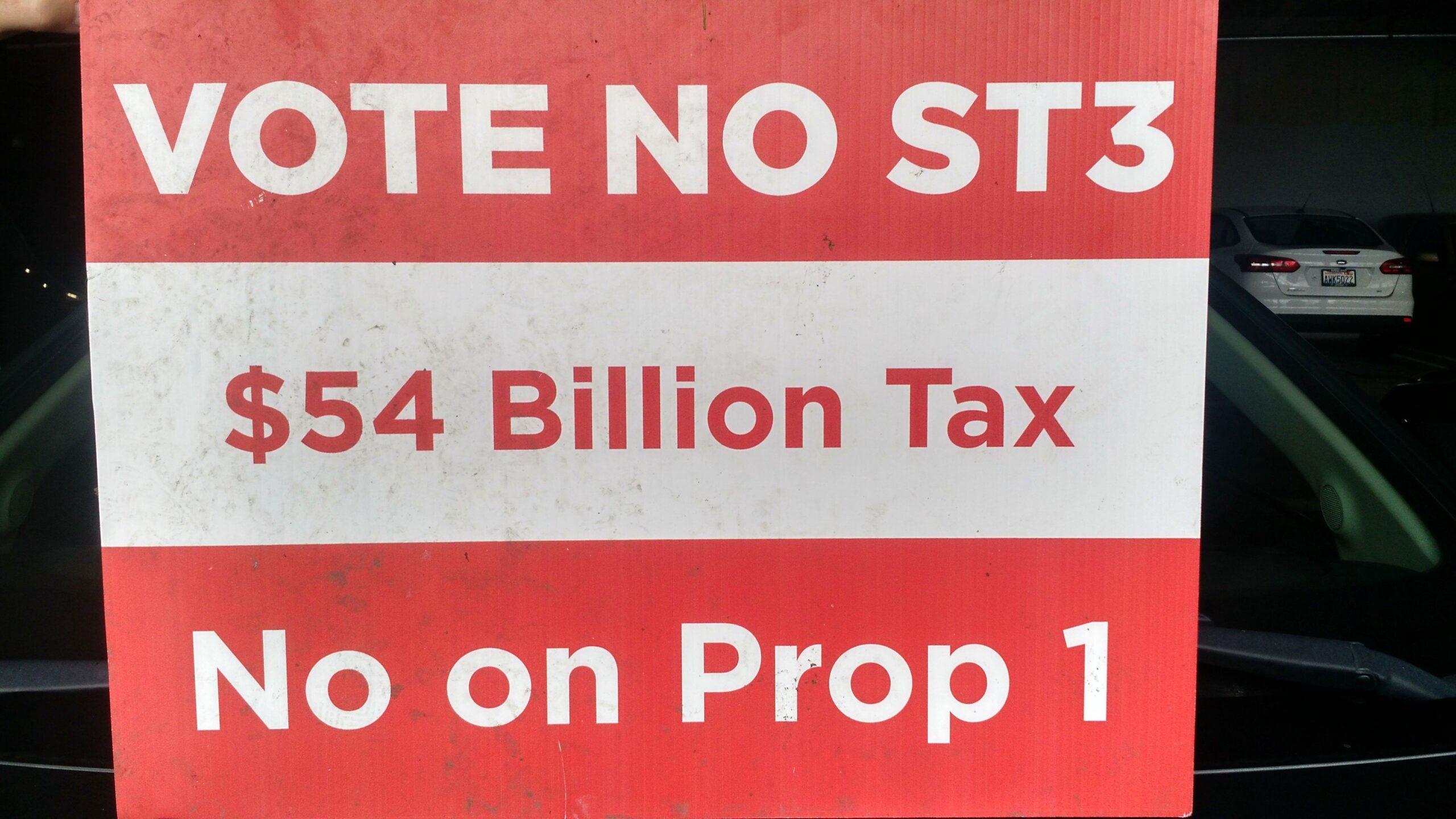

How to fix it, then? A coalition of government officials, environmentalists, transportation advocates, and tech giants are pushing Sound Transit 3 (ST3), a plan to more than double the region’s light rail system at a cost of $54 billion over 25 years. The plan will be voted on by residents of Seattle’s King County, as well as neighboring Snohomish and Pierce counties, on November 8 (there’s an election that day, too, you may have heard). And it’s not the only big transit project on the ballot. In all, more than two dozen cities and counties across the United States will be voting on transit initiatives on Election Day.

ST3, though, is particularly bold. It would lay 62 new miles of light rail across three Washington counties, running from Tacoma in the south up through Seattle and into Everett in the north, while also branching off into Redmond and Issaquah in the east. Thirty-seven new train stations would be erected across the region, along with affordable housing near some of the new transit hubs. The plan would make Seattle’s rail system about the same size as the systems in San Francisco and Washington, D.C. It would be one of the largest local transit projects in American history.

It’s also hugely controversial. Opponents say the plan is too expensive, that the government can’t be trusted to fulfill the promised timeline, and that there are more pressing problems worthy of tax dollars. These are classic gripes from those dubious of ambitious infrastructure projects that can easily mutate into “boondoggles.” (The Big Dig, anyone?) But the Seattle transit project in particular has brought forth an unusual new opposing argument: What about driverless cars?

Some think introducing autonomous vehicles to Seattle could make ST3 obsolete before it’s even complete. Instead of finishing the light rail system, there are those who would rather give up now with the assumption that driverless cars are the real transit future.

Ridesharing, driving-assistance technology, and fully autonomous vehicles threaten to fundamentally change how we navigate cities in the coming decades in ways that experts say are difficult to predict. Driverless cars are already shuttling Uber customers around in Pittsburgh and being tested by Google in the tech-centric Seattle suburb of Kirkland. How far will the technology have advanced by 2041, when Seattle’s proposed transit project would be finished? Will a sprawling, fixed rail system still be useful, even when some cities today are already experimenting with Uber as an extension of public transit?

No matter where you live in America, there’s likely a sense that public transportation is in a state of disrepair at best, or crisis at worst. Two of our nation’s biggest public transportation systems, in New York and Washington, D.C., are undergoing major repairs that will last at least a year and, during that time, will have to intermittently shut down major train lines. San Francisco’s BART is an essential need for the lower and middle classes, but is constantly wracked with delays that tech workers who glide to work on corporate buses get to ignore. Usually, we throw tax dollars at these sorts of problems, but a growing number of tech evangelists are claiming we can innovate our way out of highway gridlock and a reliance on century-old transit tech.

I visited Seattle ahead of its own decision on the matter to find out how difficult it is to travel around the city and to talk to experts about how different technologies could make moving around easier. Through four fateful rides, I learned a lot about not just the future of transit in Seattle, but how we may navigate American cities in the coming years.

The Light Rail Solution

Sunday, October 30

Seattle-Tacoma International Airport to Capitol Hill via light rail (15 miles)

Trip duration: ~40 minutes

Cost: $3.25

No one at the Seattle airport wants to use a taxi. Fewer than five people are in line for a yellow cab in the airport’s parking deck when I arrive, while at least 20 people are waiting for an Uber or Lyft in the designated rideshare pickup area, which the airport added in March. A technology that wasn’t even legal in this place a couple of years ago has now superseded a mode of travel that is decades old.

An Uber to the part of town I’m staying in would cost more than $30, so I opt to use light rail, which costs $3.25. The train is three cars long, which means it can seat 222 people, crowd 582 people, or inhumanely sardine 756 commuters willing to finagle themselves into another person’s armpit or crotch after a Seahawks game. As my trip begins, the train is comfortably full but not crowded — you can sit down, but you’d probably have to sit with a stranger. I choose to stand, obviously.

The light rail is clean and quiet, and has an easy-to-comprehend map, which are all alien features to me because I rode the New York subway every day for four years. The train car has a diverse array of folks who have opted to ride public transit: several middle-aged couples, a few parent-child pairings, a lone kid wearing pink shutter shades, some 20-somethings who look like they might attend the University of Washington (where this train line ends) and, of course, Cool Teens. A lot of people are wearing green scarves that are too bright to be for the Seahawks and not tear-soaked enough to be for the Sonics.

I talk to one of the mysteriously green-garbed people. His name is Dave Couture, he’s 49, and he lives in Columbia City, a Seattle neighborhood that got a light rail station in 2009. He’s a supporter of ST3, and already uses the light rail system to go downtown two or three times a week. In addition to the environmental benefits, he hopes an expanded light rail system will help connect different communities in the region. “Hopefully we can improve a little bit by interacting a bit more,” he says. (He also informs me he’s going to a Seattle Sounders game, which explains the scarf — Major League Soccer is huge here.)

I arrive in Capitol Hill after a 40-minute ride without incident. My trip is the ideal that light rail advocates imagine when they discuss the benefits of the train system. Sound Transit, which runs light rail, commuter rail, and some buses in the Seattle region, began in the 1990s as a Band-Aid on a region lacking a comprehensive transit system. Seattle voters rejected a proposed heavy rail transit system in 1970 that would have been mostly funded by the federal government, a decision that many transportation advocates in the community view as the city’s original transit sin (the funds instead went to Atlanta).

Decades later, in 1996, voters approved an initial $3.9 billion regional transit system that included 25 miles of light rail. A $17.9 billion expansion, dubbed ST2, won voter approval again in 2008. Sound Transit 3, this year’s ballot measure, is much more expansive — and expensive. There’s really no affordable way to fix Seattle’s transportation woes, because of its geography. Building a rail system that is “grade separated,” which means it runs independently of highway traffic, requires burrowing through tunnels, building bridges across bodies of water, and laying elevated tracks above the ground. These are all expensive endeavors — and to make matters worse, the same challenges make expanding the highway to accommodate more cars a costly and at times impractical solution.

“We’re playing catch-up to build that basic transportation infrastructure, which is why ST3 is so big and so bold,” says Shefali Ranganathan, executive director of the Transportation Choices Coalition and a key backer of ST3. “It’s kind of a moonshot, but the magnitude of the issue we’re confronting reflects the response in terms of this plan.”

Traveling around the city over the next day, most of the people I talk to are in support of the light rail — especially folks I encounter who are waiting for the bus. Austin Veloria, a 36-year-old hospital administrator and lifelong Seattle resident who supports ST3, doesn’t have a car. He uses a mix of Uber, public transit, and Zipcar to get around. “I just think people need more access to public transportation,” he says as he waits at a bus stop in Ballard, a northern Seattle neighborhood. “I’d rather see my money go to something like that. I’d probably go further north more often.”

But it took Seattle 20 years to make that train trip I took from the airport to the apartment I was staying at possible — the Capitol Hill light rail station didn’t open until March 2016. And the station in Ballard that would give Veloria an alternative to the bus wouldn’t be online until 2035. “I think that sucks,” he told me.

The Ridesharing Robo-ride

Tuesday, November 1

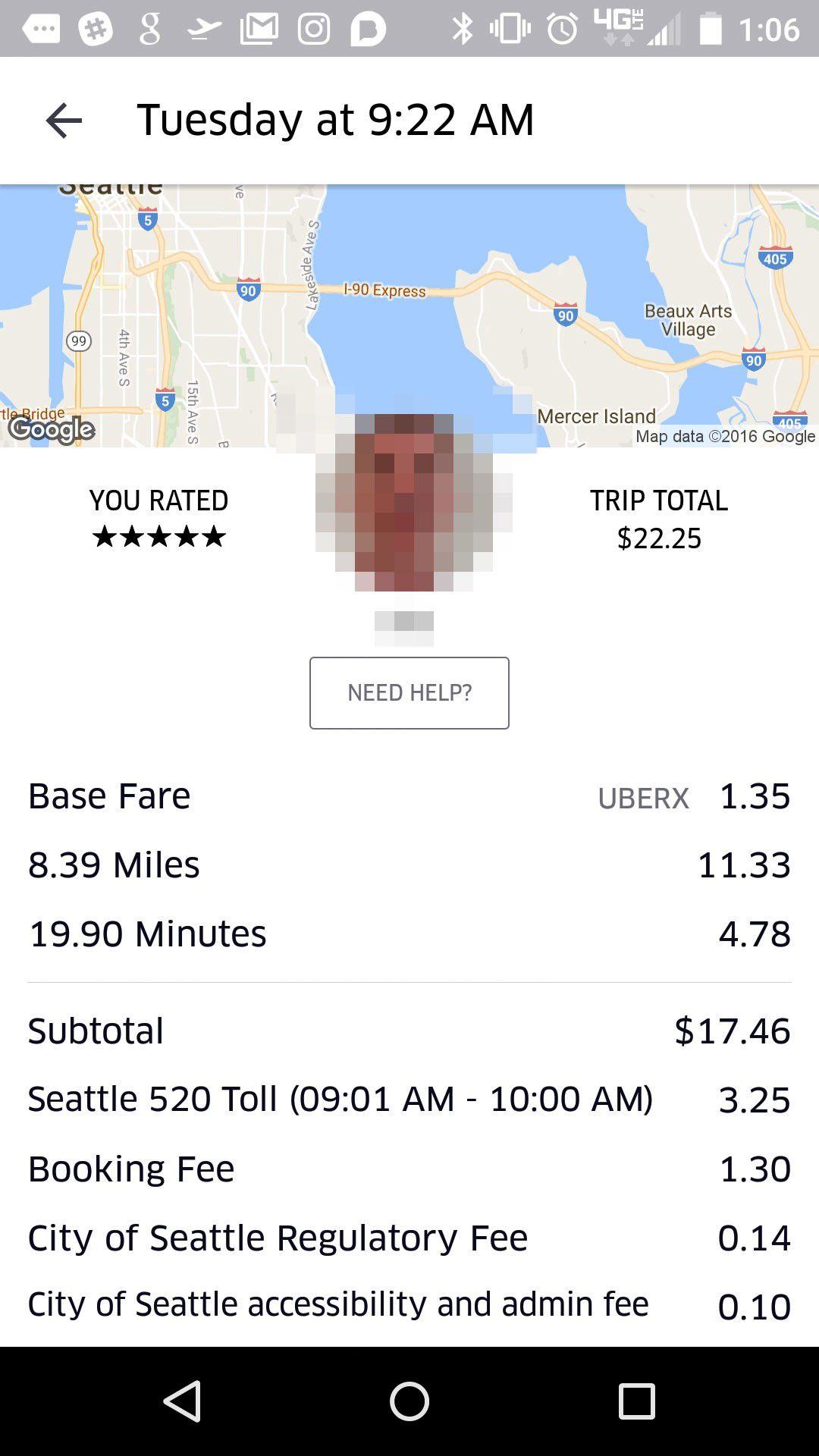

Capitol Hill to Kirkland via Uber (8.39 miles)

Trip duration: 19.9 minutes

Cost: $22.25

Not everyone thinks doubling the size of Seattle’s light rail system is a good idea. On Tuesday, I take an Uber from Capitol Hill to Kirkland to visit INRIX, a transportation analytics company that’s not buying into the ST3 hype. The company’s CEO, Bryan Mistele, published a column in The Seattle Times over the summer denigrating the transit plan. “Sound Transit’s expansion will be obsolete before it’s built,” the headline proclaims.

Bob Pishue, INRIX’s senior economist, agrees with his colleague. “We just see a lot of opportunity in the autonomous, connected, electric, and shared vehicle space,” he says. “Rail is a long-term investment, and it’s not going to be fully built out until 2041. What is the world going to look like in 2041? Light rail way out to the suburbs doesn’t make much sense from a mobility aspect.”

Pishue paints a picture of how driverless cars could work in Seattle by 2041. Let’s call it the Brightest Timeline: Because an autonomous vehicle can now be summoned in two minutes or less from anywhere in the Seattle region, no one needs to own a car anymore. Commuters who don’t live near public transit can summon an Uber, Lyft, or other robo-taxi for their daily trip to work. Because Ubers no longer require drivers, the cost of a trip is significantly reduced — and remember, you never had to buy a car, so that’s tens of thousands of dollars in purchasing and maintenance costs saved. You’re sharing this robo-ride with three of your neighbors to increase travel efficiency (maybe four, because we all drink Soylent for meals now and everyone is skinny).

On your trip down the interstate toward downtown Seattle, there is no traffic congestion on a road filled with autonomous cars. First of all, the cars are too smart to get into accidents, which cause 20 percent of congestion, according to Pishue. And because there are no drivers fiddling with the radio, or texting, or arguing with their kids, or driving 65 mph in the left lane like an asshole, the cars are able to maximize the use of the roadway by cruising along in perfect harmony rather than constantly starting and stopping. A congested highway can move only about 700 cars per hour per lane, according to Pishue. With the efficiencies realized through autonomous cars, a highway could move up to 3,000 cars per hour per lane. With carpooling now common practice and more cars crammed onto the road, congestion has largely been thwarted.

“We’re going to use our current infrastructure much more efficiently,” Pishue says. “I think that’s where you get the large benefits as opposed to extending rail out of Issaquah,” a city about 20 miles east of Seattle whose residents suffer from an unfortunate commute in and out of the city.

The premise may seem far-fetched, but governments and tech companies are already quietly laying the groundwork for this kind of mobility. After voters in Pinellas County, Florida, rejected a transit project that would have included light rail, Uber partnered with local officials to offer rides that were subsidized by the government, effectively replacing some area bus routes at a lower operational cost. In other cities, such as Atlanta, Lyft has offered discounts for travelers headed to a rail station. As these efforts grow more ambitious, it’s easy to imagine voters or city planners in some communities deciding ridesharing is an effective replacement for traditional transit, especially with the cost savings and driving efficiency that autonomous cars would provide.

Mark Hallenbeck, director of the Washington State Transportation Center at the University of Washington, has a more skeptical view of this driverless future, though. He paints a picture that we’ll call the Darkest Timeline: It’s 2041, and many people own their own driverless cars, because (a) we’re Americans, goddamnit, and (b) no one wants to wedge into an UberPool with three other fat, smelly riders (McDonald’s acquired Soylent in 2027). There are still tons of cars with only one passenger each on the road. In fact, there are some cars with no passengers. People who work in downtown Seattle now send their cars back to their homes in the suburbs rather than pay for parking. That means these vehicles are actually making four trips up and down the interstate for a daily commute instead of just two, doubling the number of cars on the road per day.

In downtown, meanwhile, driverless cars haven’t realized the same efficiency gains they achieved on the highway because navigating city traffic is much more complex. When 5 p.m. rolls around, a crush of autonomous cars descend on a single office building at the same time. There isn’t even enough curb space to allow all the workers to safely board their vehicles. Instead of waiting, bored on their phones, in traffic on I-5, these workers wait, bored on their phones, standing outside their office building for their cars to fight for a curbside spot. “That’s the dystopian view of what happens with automated cars,” Hallenbeck says, “but it fits really well with the view of how humans interact with technology. We’re not interested in the social good of everybody working together. We’re interested in me.”

The true utility of driverless vehicles will likely land in the middle of these two extremes, but anyone who tells you they know exactly how the technology will reshape society is lying. Some, like Pishue, view that ambiguity as an opportunity — we’ll be able to shape this technology to make the best possible use of it in our cities. Others see it as a distraction from the slow, deliberate work of building infrastructure that has defined urban development for a century. “Whether you come in heaven or hell with automated cars,” Hallenbeck says, “is a function of which unknowns sprawl in which direction.”

Monorail! That’s Right — Monorail!

Tuesday, November 1

Westlake Center to Seattle Center via monorail (1.2 miles)

Trip duration: three minutes

Cost: $2.25

Seattle has a curious history of infrastructure mishaps that sound more like TV show plotlines than real life. Right next to City Hall, where a municipal building used to stand, there’s now a giant block-sized pit that’s a result of a stalled plaza development project (it’s not unlike the pit Andy tumbles into in the first season of Parks and Recreation). The ambitious light rail expansion itself echoes the 1992 rom-com Singles, in which Campbell Scott’s Steve Dunne dreams of building a “super train” that will connect all of Seattle. And of course, there’s the genuine, bona fide, electrified, two-car monorail.

Along with the more famous Space Needle, the Seattle Center Monorail was built as a futuristic attraction for the World’s Fair in 1962. It was the first full-scale monorail of its kind in the United States, according to the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, able to achieve speeds of up to 70 miles per hour and expected to shuttle 10,000 passengers per hour to and from the fair. Government officials thought it was the beginning of an ambitious new transit system that would eventually snake its way over the entire city.

I ride the monorail twice, on a Monday and a Tuesday afternoon. The train has a capacity to hold 200 people. On my first ride, there are four other people on the train. The second time, there are seven (the monorail website claims 2 million people use the train every year, often after sporting events and festivals). Mostly they are tourists, clutching city maps or filming the buildings we glide past with their smartphones. One Seattle resident I talk to says he uses the monorail a couple of times a year, when it’s convenient (he doesn’t know anything about ST3).

The city has tried to make good on its dream of a mass transit monorail system, but to no avail. A proposal for a 40-mile monorail dreamed up by a former taxi driver won voter approval in 1997 but never gained the funding to be implemented. Another effort in 2002 again won at the ballot and even levied a car tax to generate revenue, but still wasn’t implemented. The Monorail Movement, as it’s known, was revived yet again in 2014, but soundly voted down.

Sound Transit doesn’t operate the monorail, but that detail can be lost on residents who have lost faith in the government’s ability to be an effective transportation provider. It seems in some minds, the failure of the monorail is looped in with the slow-going implementation of the light rail — bad news for ST3 advocates. “It’s one after another,” one of my Uber drivers, Eric, tells me of the transit proposals on a trip between Capitol Hill and Kirkland (he asks me to withhold his last name for fear of reprisal from Uber). Eric, who is in his mid-50s and lives outside Seattle, calls the light rail expansion a “scam” that won’t help alleviate traffic (when asked directly, ST3 backers cast light rail as an alternative to congestion, not a cure). “This state is like most liberal states — they just suck money and waste it,” Eric says. “They know [ST3] is what most millennials visualize as a good thing.”

Eric also has choice words for the tech companies and workers who are supporting the proposal (Microsoft, Amazon, and, surprisingly, Uber, all back ST3) despite its high cost. The average Seattle-region resident will have to pay $169 in additional taxes per year for decades to fund ST3. The Seattle Times has estimated the total bill for all of the Sound Transit projects at $20,000 per household over 25 years. “[Tech employees] are sort of in an altered reality of what it takes to live,” he says. “They don’t know what it takes for a family to live.”

The Old-School Model

Tuesday, November 1

Bellevue to downtown Seattle via bus (10.2 miles)

Cost: $2.50

Duration: 24 minutes

My last task in Seattle is to try to navigate the Byzantine bus system. There are diesel, hybrid, and electric buses. Some are run by Sound Transit and others by King County Metro Transit. There’s a fleet of express buses, known as RapidRide, and others that run slower, traditional routes. And there are trolley buses that make use of the electric wires that hang over many of the city’s streets, a holdover from the pre–World War II era when streetcars were a common mode of transit downtown. It’s obvious that these buses have become as essential to Seattle residents as light rail or personal cars. Just like I-5 clogs with people as evening approaches, the lines at bus stops in the heart of the city can run dozens of riders deep.

John Niles, a transportation researcher and longtime opponent of Sound Transit’s light rail proposals, is a proponent of these buses as a primary solution to the region’s transit problems. They’re more flexible than light rail, which has fixed positioning, and could eventually benefit from automation in the same way personal cars will. “The problem with ST3 is [it won’t work] in the long run,” Niles says. “You can say, ‘Roads are bad, we’re building too many.’ But we’re going to have roads. I think exploiting them and giving transit priority on them when it’s appropriate is the way to go.”

After I leave Niles and am on my own trying to make my way back to downtown Seattle, I meet a 54-year-old Bellevue College student named Kevin Chase on a crosstown bus. He rides four days a week, and it takes him an hour and 40 minutes to travel around 14 miles one way (including a transfer). He’s taking an art class on bronze sculpture. He shows me a video of his work from the day, pouring metal heated to 2,300 degrees into a cast. “Bronze sculptures can last 5,000 years,” he tells me. “I feel real connection to humanity through this process.”

If ST3 is approved and a light rail line is built between West Seattle, where Chase lives, and Bellevue, where his classes are, his commute would be cut to 40 minutes, he estimates. But light rail wouldn’t reach his neighborhood until 2030. The line connecting his neighborhood to downtown, by itself, would cost $1.5 billion to build and $15 million per year to maintain. Will Chase still be building spiritual connections via sculpting classes in 14 years? Will Sound Transit have made good on its promises? Will Uber’s robotic cars (or Google’s, or Ford’s) have taken over the streets and effectively replaced the rails?

Even though no one can answer these questions definitively in 2016, Chase is an ST3 supporter. He’ll place his faith and money in the slow-moving cogs of municipal government rather than the “move fast and break things” ethos of Silicon Valley.

“Whatever it costs, we need to get started right away or it’s going to cost even more,” he says. “I’m talking about society — everybody chipping in for the betterment of everybody.”