The best way to convey the ludicrous length of the modern American presidential campaign might be to compare it to another long-in-the-tooth (and lately, just plain long) patriotic tradition: baseball. The baseball season is protracted by major-sport standards, lasting more than eight months from the first out of spring training to the last out of the World Series. It’s so grueling, in fact, that 55 years after the schedule’s most recent expansion, Major League Baseball’s commissioner is considering cutting back. But baseball moves much faster than our process for picking a president.

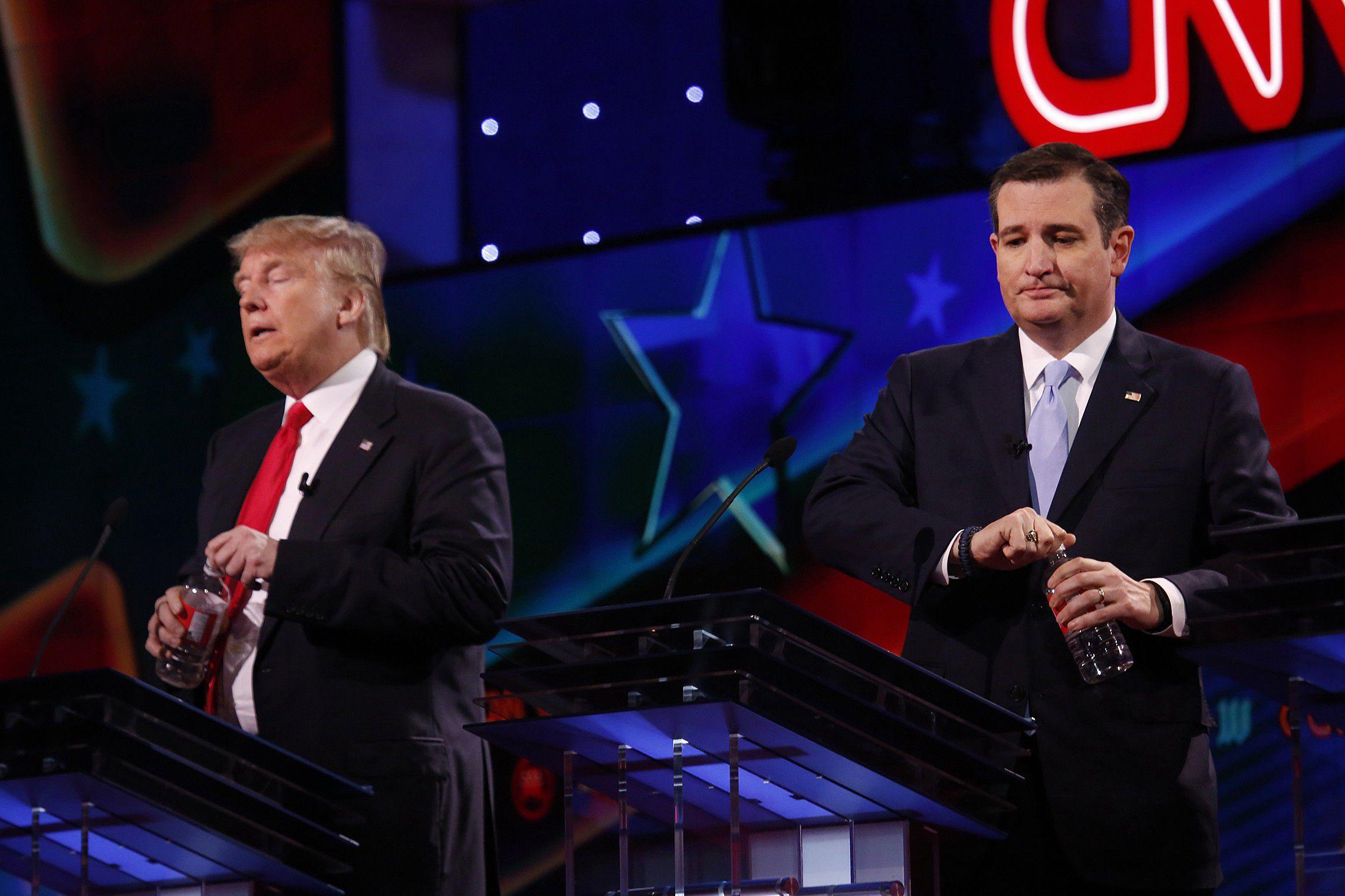

The 2016 presidential campaign season officially started at 12:09 a.m. ET on March 23, 2015, when an unsuspecting Ted Cruz — still months away from being nicknamed, linked to two famous murders, or forced to respond to an opponent’s attacks on his wife — tweeted his intention to run, along with a video in which he beat Donald Trump to the phrase “Make America great again.” On that day, the big story in baseball was whether the Chicago Cubs would try to extend their control over top prospect Kris Bryant by sending him to the minor leagues to start the 2015 season. Bryant, who ended up making his major league debut in the team’s ninth regular-season game, went on to win the National League’s Rookie of the Year Award, and the Cubs improved by 24 wins and claimed a wild-card berth before being defeated in the championship series. At that point, the presidential primary race was less than half finished.

When baseball came back, Bryant had a brilliant sophomore season, and the Cubs won 103 regular-season games and, at long last, the World Series. When their parade reached Chicago’s Grant Park, the presidential race was still a few days from its surprising conclusion. Between Cruz’s tweet and the moment when Trump realized he’d have to find out what a president does, two baseball seasons (broken up by one winter) elapsed; Bryant went from being a prospect his team could stash in the minors to a presumptive MVP, and the Cubs went being from a perennial loser coming off a last-place season to reigning champions.

Granted, electing the world’s most powerful political leader is a task with greater ramifications than the outcome of two baseball seasons (even if one broke a curse). There’s no need to rush, if the extra time teaches us something. Still, it took 597 days to declare a winner, and that’s not even counting the “invisible primary” months of hinting and jockeying that preceded the first official announcement. Historically, there have been benefits to drawn-out campaigns, but due to unprecedented party polarization, the upsides seemed smaller than ever this cycle, and the fatigue more acute (although the latter likely had as much to do with negative discourse and disliked candidates as it did with an interminable contest). Almost four months before the election, 59 percent of respondents to a Pew Research survey reported feeling “exhausted” by campaign coverage; by Election Day, 85 percent told exit pollsters that they “just [wanted] it to be over.” Unfortunately for American consumers who’ve had enough of meta-pollsters and pundits alike, the current system’s incentives are set up to perpetuate the “permanent campaign.”

“Presidential campaigns take too long” is not a new argument. Campaigns have been trending longer since the early 1970s, when changes to the nomination process after the upheaval of 1968 inspired more states to hold primaries, and some to “front-load” their primaries in a bid to beat the slowpokes to the punch. When lesser-known candidates — most notably Jimmy Carter in 1976 — took advantage of those early contests to boost their name recognition, the race to the race was on.

Our modern Energizer elections are the descendants of those ’70s contests. They come with several side effects even aside from voter fatigue, including increased opportunity cost to the country (in time and money), the need for elected officials to spend large portions of their terms running for reelection, and, perhaps, an increased focus on penis size and other side stories that obscure more meaningful issues. “I think shorter campaigns — actually, quite short ones — would be highly beneficial for the quality of our politics,” says James Gardner, an election-law professor at the University at Buffalo School of Law and one of several election-law specialists I consulted via email. “It would encourage people to focus on substantive issues during the campaign because there would be little time to get diverted onto the kind of frivolous matters that unlimited time now allows.”

However, the not-so-new normal’s roots run deep. “Our lengthy campaigns are a function of two features of our system no one is likely to change: 1) a nomination process driven primarily by primary elections, so that we actually have two adjacent campaign periods instead of one; 2) our presidential system, which includes regular, periodic elections, in contrast to a parliamentary system in which the prime minister can and does call an election on relatively short notice,” says Daniel Lowenstein, director of UCLA’s Center for the Liberal Arts and Free Institutions (and a professor emeritus at UCLA Law).

While it’s hard not to feel election envy when we look at the more tolerable lengths of other countries’ campaigns, it’s easy to overlook the fundamental differences that contribute to those gaps — many of which we wouldn’t want to lose. “People often say, ‘Why can’t we be like England, where the campaign is six weeks?’” says Bradley Smith, an election-law professor at Capital University Law School. “Of course, the major difference is that there, the governing party can essentially choose when to call an election. Ours are set at a certain date, so everyone knows when the next presidential election is, and you can start campaigning.” In most countries, as in the U.S. prior to the primary system’s ascendance after World War II, plenty of low-key campaigning takes place outside of the official election period, but it doesn’t loom as large in the public eye.

Smith believes that the most effective way to shorten campaigns would be to eliminate primaries. “Do away with primaries, and I suspect most candidates would declare sometime between January and June of the actual election year,” he says. While a 5–10 month election cycle sounds enticing, we’d lose a lot of the influence we wield over the selection of major-party candidates, who used to be chosen by members of Congress and, later, party bigwigs. Shorter campaigns probably wouldn’t be worth ceding control over candidates — although in retrospect, anti-Trump voters would have happily signed up for that system in 2016.

One supposed benefit of long campaigns is that they make it easier for less experienced, non-incumbent candidates to raise their national profiles or sell voters on the vision of them as commander in chief. That’s a double-edged sword — in some cycles it benefits Barack Obama, and in others it benefits Trump — but on the whole, helping underdogs is something most Americans support. In another way, though, the current system excludes unknowns. Long elections require candidates to spend enormous amounts of money, which would disqualify many aspirants who aren’t as independently well-known and wealthy as Trump (let alone as wealthy as Trump says he is).

The huge sums involved have a sort of reinforcing effect. To generate sufficient funds for long campaigns, candidates have to spend more time raising money. Yet at the same time, the knowledge that some candidates can count on giant war chests gives them the impetus to declare early, knowing that they can last for the long haul. “If we lived in a world of publicly financed political campaigns, then you might be able to get people to limit the period during which they’d campaign in exchange for public money,” says Daniel Tokaji, a professor of constitutional law at Ohio State’s Moritz College of Law. “We technically have presidential public financing on the books, but the amounts haven’t kept up with the cost of campaigns, so no serious candidate uses it anymore.” Even in the world Tokaji is talking about, one wouldn’t be able to stop rich candidates from using their own money to buy early ads.

Smith estimates that removing donation limits might strip nine months from the campaign process, because candidates wouldn’t have to scrape together their stockpiles in increments of $2,700 (or less) at a time. “In 1968, Eugene McCarthy declared his candidacy challenging an incumbent president on November 30 of 1967, with the New Hampshire primary just 3 1/2 months later,” Smith says. “A group of wealthy, anti-war supporters contributed amounts of (in today’s dollars) up to millions each, so fundraising took no time and McCarthy could be immediately competitive. Today you can’t do that.” But given the potential for corruption and preferential treatment, allowing mega-rich donors to spend without restrictions is an even scarier prospect than eradicating primaries.

In theory, the thing that today’s system should be best at is uncovering candidates’ flaws. Not only do our current campaign timelines give competitors and journalists plenty of time to unearth nasty secrets in aspiring presidents’ pasts, but relentless public-appearance schedules give each hopeful countless pressure-packed opportunities to slip up and reveal some side of their self that seems ill suited to the office. In the latest cycle, though, that feature failed in the face of fake news that was widely disseminated and record partisanship that made the letter next to the candidate’s name matter more than his or her individual attributes. Trump won 90 percent of self-described Republican voters despite his many offensive actions, lack of endorsements, and positions that conflicted with the GOP party line. “With few exceptions, Republicans vote for the Republican and Democrats vote for the Democrat — pretty much no matter what,” FiveThirtyEight’s Harry Enten concluded. As the exceptions grow scarcer and straight-ticket voting reaches record levels, a years-long vetting process increasingly seems like a waste of the world’s time.

The response might seem simple: There oughta be a law. But constitutional protections can prove pretty pesky when it comes to compelling people not to announce that they’re running for president. “Other developed democracies place firm limits on campaign length simply by legally prohibiting it beyond a relatively small window,” says Michael Kang, a professor at Emory University School of Law. “Our First Amendment doesn’t allow the government to prohibit campaign speech in the same way.” Every expert I asked who expressed an opinion said they couldn’t imagine such an amendment passing. “The presidential campaign season goes on much too long — actually, I think the 2020 campaign is about to start right now — but this idea is probably a non-starter for free-speech reasons,” Tokaji adds. “Campaign speech is considered core political speech, which gets the highest level of constitutional protection.”

If an amendment is unrealistic, what other options are out there? “An easier lift is for media outlets and sponsoring organizations to hold their primary debates later,” Kang says. “Such early debates create incentive and pressure to declare earlier, while an announcement that televised debates wouldn’t start until, say, November might decrease those incentives and pressures.” However, there’s no obvious reason why media outlets would want to pass up the free programming campaigns provide, not to mention the money that flows to local TV stations when political ads proliferate.

That leaves an appeal to the parties to hold later primaries and caucuses — the Sheryl Crow route. “What we can do is control the presidential primary schedule,” says Jamie Raskin, the director of the Law and Government program at American University’s College of Law (and as of last week, an incoming U.S. representative), via phone. “That’s a matter of state law. … You’d need leadership from the DNC and the RNC to get everybody to move it up.” Of course, just as candidates have incentive to start their runs early, parties probably have incentive to wrap up their primaries, announce a nominee first, and reap the resulting bump in the polls. There’s also the possibility that the flaw could be better than the fix. “One tried-and-true rule of reforms put in place by the RNC and DNC is that they are going to have unintended consequences much worse than whatever problem they were designed to solve,” says Dan Pfeiffer, a former senior adviser to President Obama and a cohost of The Ringer’s politics podcast, Keepin’ It 1600.

To circle back to a baseball analogy, the “never-ending campaign” problem is a little like the epidemic of arm injuries among pitchers. No one wants pitchers to get hurt, but everyone wants hard-throwing pitchers — and in turn, every pitcher wants to throw hard, even though that raises the risk of shredding an elbow. Similarly, no one (except the media, maybe) wants endless campaigns, but everyone wants the benefits that come from starting sooner. “How would you persuade the various actors who want to win the nomination not to start competing for it when they think it is in their interest?” asks Richard Pildes, a constitutional law professor at NYU School of Law. There’s no obvious answer to that question that would produce a drastic difference without an equally drastic restructuring.

“I think long campaigns are baked in, and we don’t really want to shorten them — at least in the sense that we are unwilling to do the things that would actually shorten our campaigns,” says Smith. We can hope for future election seasons to feature friendlier campaigns, better-liked candidates, and less divisive victories, but anyone rooting for faster resolutions is likely out of luck. Which leads to one silver lining: If you’re unhappy with how 2016 turned out, today isn’t too early to kick off your 2020 campaign.