The Cubs are the best team in baseball, but there were two glaring ways in which even we — the people confined to our couches due to a lack of athletic talent — were convinced they could be beat when the World Series began. Each way had to do with a weakness in one of the players who’d propelled the team to a pennant: co-NLCS MVPs Jon Lester and Javier Báez.

Lester’s weakness — an inability to throw to first base — has been national news since September 2014. While it seemed as if the Indians’ elite baserunning skills made them the ideal team to take advantage of his quirk, only one Cleveland runner (AL stolen-base leader Rajai Davis) succeeded in swiping second off Lester without being caught at least once. The only other player to steal off Lester, Francisco Lindor, was also thrown out twice. Even though Lindor saw in Game 1 that leaving too early against Lester comes without consequences, and even though he watched Davis take a lengthy lead, he couldn’t bring himself to go against his training and stray farther from the bag. Instead, Lindor took more conservative leads and lost to the Lester–David Ross battery, which earned him a talking-to from Davis after his inning-ending out in Game 5.

Even as Lester flourished, though, Báez’s vulnerability lived up to its billing. Through the first two rounds of the postseason, Báez was the breakout Cub. In four NLDS games, the 23-year-old batted .375/.412/.563, with one dinger. In six NLCS games, he hit .318/.333/.500, with two steals (including a steal of home). At some point during that run, every website (The Ringer included) ran an ode to his talent and infectious style of play. Báez is a defensive whiz, so when he’s hitting, he looks like one of the best players in baseball. During his hot streaks, it’s hard to remember that he was a below-average hitter during the regular season, with the third-worst walk-to-strikeout ratio among players with at least 400 plate appearances.

Báez started the season in Triple-A, and at times he looks like he still belongs there. Among the 302 hitters who saw at least 1,000 pitches during the regular season, only 10 swung at a higher percentage of the ones outside the strike zone. In related news, only 12 saw a lower percentage of pitches inside the strike zone, as pitchers went after his weakness. Báez also had a tough time hitting sliders, curveballs, and changeups, performing worse than the typical batter against all three pitches. The book against Báez is so simple that you and I know it, without high-level playing experience or access to advance-scouting reports: Don’t throw him a pitch in the strike zone, particularly with two strikes. Instead, expand the zone, preferably with something that spins.

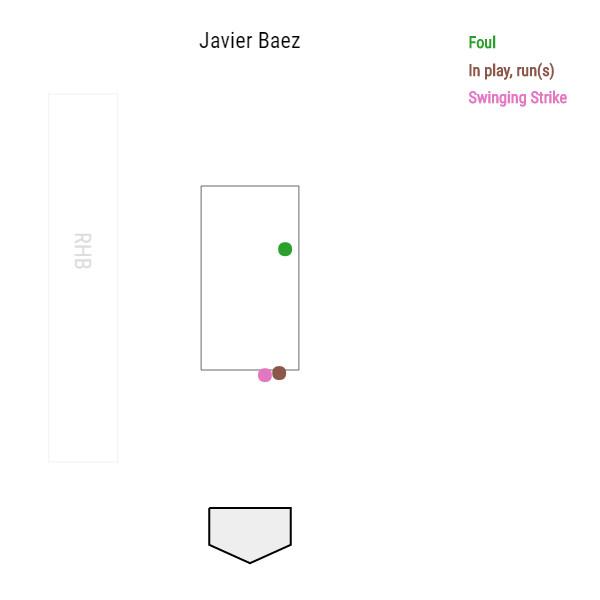

Straightforward as it sounds, the Cubs’ first two playoff opponents ignored or failed to follow that advice. Báez’s biggest hit of the postseason, by championship win probability added, was the ninth-inning single off Hunter Strickland in NLDS Game 4 that gave the Cubs the last lead they’d need in that series. It came 0–2, when Strickland — ignoring the option of wasting multiple pitches — inexplicably threw a fastball at the edge of the strike zone.

According to Pitch Info’s called-strike probabilities — which are based on location, count, year, pitch type, and batter/pitcher handedness — Strickland’s pitch had a 54.2 percent chance of being a strike, had Báez not swung, even though the strike zone contracts on 0–2. But Báez didn’t take it. Instead, he connected to send San Francisco home.

Four days earlier, Báez had beaten the Giants with his second-biggest hit of the series by cWPA, an eighth-inning homer off Johnny Cueto that broke a scoreless tie. That pitch, a full-count fastball, was almost dead center, with a 99.3 percent chance of being a strike.

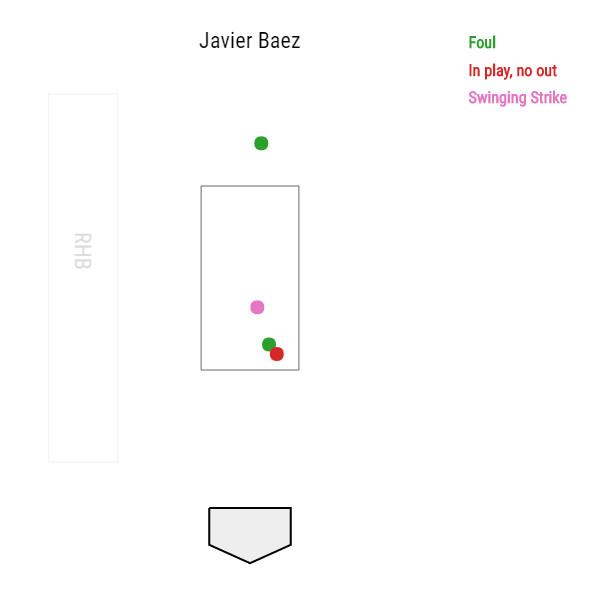

Báez’s three biggest hits of the NLCS also came off likely strikes. In Game 5, Báez doubled on a 2–2 curveball from Kenta Maeda that caught a lot of the plate (84.9 called-strike probability) and, more forgivably, singled on a Joe Blanton borderline first-pitch slider (59.3). In Game 4, Báez helped set up a four-run rally with an 0–2 single off Julio Urias, who made the mistake of throwing something meaty — a changeup with a 79.3 percent called-strike probability — after getting Báez to chase on the previous pitch.

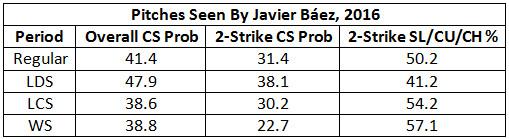

The average pitch thrown during the 2016 regular season had a called-strike probability of 45.9 percent; the average two-strike pitch had a called-strike probability of 36.6. The baselines against Báez (41.4 percent and 31.4 percent, respectively) were both far below league average, reflecting his tendency to swing at pitches far from the center of the strike zone and pitchers’ willingness to exploit it. Here’s how his opponents have pitched him in the postseason so far:

The Giants totally flunked the Báez test, throwing him more hittable pitches than the typical player sees, even with two strikes. They deserved to be dominated in Báez’s at-bats. The Dodgers did a better job, but they still challenged him with two strikes at roughly a regular-season rate.

The Indians, by contrast, have completely pressed the advantage. The typical two-strike pitch Báez has seen through the first five games of the series has been far from the strike zone’s center, with a called-strike probability barely better than 1 in 5. And even more cruelly, Cleveland has called for his off-speed/breaking-ball kryptonite almost 60 percent of the time in two-strike counts.

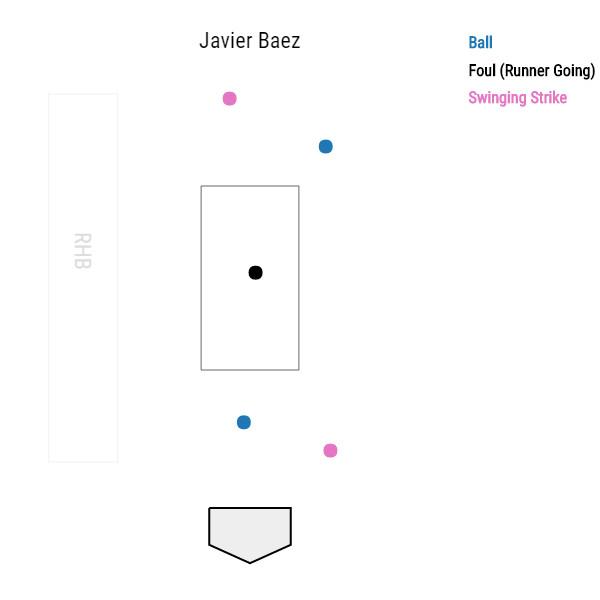

By cWPA, the most momentous non-hit of the postseason so far was Báez’s ninth-inning strikeout against Cody Allen in Game 3, with the Cubs down 1–0, two outs, and both the tying and go-ahead runs in scoring position. The at-bat embodied the Indians’ merciless attack. Báez, to that point, was 2-for-12 in the series without an extra-base hit, and his mini-slump had exposed him as easy to neutralize. Allen and catcher Yan Gomes proceeded to pick him apart, further solidifying the perception that Báez is beatable.

On only the first pitch, a centered four-seamer, did Allen approach the plate. After that, his pitches’ called-strike probabilities almost flatlined, registering as zero, 1.1, zero, and zero. He threw pitches out of the zone in four different directions: up and away for a ball; over the plate but low for ball two; low and away with a curve for a swinging strike; and finally, way, way up with a fastball.

The last pitch got a game-ending whiff.

“I just keep chasing out of the zone and didn’t make my adjustments,” a frustrated Báez said after Game 3. Until he does, the Indians will keep trying to turn his own inclinations against him, like a bully yelling “quit hitting yourself.” Although his tagging skills are intact, Báez is now batting .143/.143/.143 through 21 World Series plate appearances, and his biggest hit came on a bunt. He’s struck out more in five games against Cleveland than he did in 10 combined games against San Francisco and L.A., and he hasn’t walked.

It’s easy for us to say from afar that the Indians are only doing the obvious; we’re too bad at baseball to be beholden to the instincts that safeguard seasoned players, keeping them close to the bag with a lefty on the mound, or close to the strike zone with a hitter who’s ahead in the count. It’s one thing to pitch Báez the way Allen did in MLB: The Show; it’s another entirely to do it at a climactic moment in the World Series, when a walk loads the bases and a wild pitch or passed ball ties the game. The Indians have not only adopted the right plan against Báez through the first five games of the series, but have implemented it perfectly, thereby robbing the Cubs of their most valuable batter from the first two rounds.