Of all the things this year’s playoff participants struggled to do during the regular season — operate drones, throw to first base, avoid fouling balls off their face — the Dodgers’ inability to hit left-handed pitchers may well have been the most glaring. L.A.’s stats against lefties (.213/.290/.332) weren’t just bad by playoff-team standards; they were also bad by Braves standards, Phillies standards, and Reds standards. In fact, the Dodgers’ park-adjusted production against southpaws was worse than any other team’s, even with pitchers’ offense excluded.

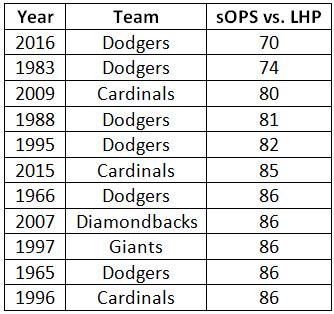

By historical standards, L.A. looks like even more of an outlier. The Dodgers’ split OPS against lefties — that is, their OPS against lefties relative to the league’s OPS against lefties — was 70, where 100 is average and lower is worse. Only three teams on record have ever finished sub-70, and those three — the 1958 Senators, the 1963 Colt .45s, and the 1982 Astros — had a combined .427 winning percentage. The Dodgers’ split OPS against lefties is the lowest ever for a team that made the playoffs, and it’s not particularly close.

When the postseason starts, we pick each team apart in search of some flaw that might mean its undoing. It’s hard to find flaws on the Dodgers. They’re solid on defense and above average on the bases, and no NL bullpen was worth more to its team. Better yet, L.A. may stand to benefit more than any other contender from the postseason’s compression of pitching staffs. As Jeff Sullivan noted, the Dodgers could distribute roughly half of their postseason innings to Kenley Jansen, Clayton Kershaw, and Rich Hill — on a per-inning basis, the fourth-, sixth-, and 21st-most effective pitchers in baseball. Kenta Maeda and (perhaps) Julio Urias will round out October’s deepest rotation.

Which directs our attention back to the team’s lone easily pinpointed weak link: its struggles against southpaws. As weaknesses go, this isn’t one of the worst. The Dodgers won 91 games despite the entire team hitting like Freddy Galvis when lefties were on the mound. They even had an above-average offense, overall, and baseball’s best offense in the second half. That’s because no other team punished right-handed pitching like the Dodgers did. The Dodgers picked the less costly side to be bad against: Even though teams were presumably trying to give the Dodgers more looks against lefties, Dodgers batters still faced righties in almost 2.5 times as many plate appearances.

With apologies to Whitesnake, though, it can’t be good to be bad, even if it’s only against lefties. Scott Van Slyke’s injuries and extended slumps by Yasiel Puig and Kike Hernández deprived the Dodgers of three of their expected lefty mashers for large stretches of the season, leaving them with a lefty-heavy lineup; only five other teams took a higher percentage of their plate appearances from the left side of the plate this season. That left-side skew played at least some part in the difficult roster decisions Dodgers brass made down the stretch: In August, Andrew Friedman defended his divisive trade of clubhouse favorite A.J. Ellis for Phillies catcher Carlos Ruiz by citing the right-handed Ruiz’s ability to lengthen the lineup against lefties.

If anything, one might expect the Dodgers’ southpaw problem to be magnified in October, when managers get more aggressive, dipping into deep bullpens to play for platoon advantages. However, there are two reasons to think that the Dodgers’ lefty troubles aren’t acute enough to cost their fans (or Friedman) sleep heading into postseason play.

For one thing, the Dodgers’ lack of offense against lefties isn’t about to become a bigger problem for L.A. than it has been for the past six, mostly successful months. In general, the playoffs are only slightly more lefty-leaning than the regular season: In the wild-card era, lefties have pitched 26.7 percent of regular-season innings and 28.5 percent of postseason innings. The best news for Dodgers hitters is that they don’t have to face Dodgers pitchers. Lefties, including Kershaw, Hill, and Urias, accounted for 41.9 percent of the Dodgers staff’s batters faced, tops in the NL. And fortunately for L.A., the Dodgers’ NL opponents aren’t especially well suited to take advantage of the Dodgers’ apparent vulnerability. The four other NL playoff teams combined to use lefties only 23.9 percent of the time in 2016, below the 26.0 percent MLB average. The Nationals, L.A.’s NLDS opponent, checked in at 23.2 percent. The Nats will likely carry three lefty relievers — Sammy Solis, Marc Rzepczynski, and either Oliver Pérez or Sean Burnett — but the only lefty in their playoff rotation is presumptive Game 3 starter Gio González, who’s coming off his worst-ever full season and ended the year by allowing 12 runs in 13 innings over his final three starts.

Only one of the Cubs’ probable starters (Jon Lester) is a lefty, and Steven Matz’s season-ending elbow and shoulder injuries robbed the Mets rotation of the only lefty it had left. That makes the Giants, who’ll throw Madison Bumgarner and Matt Moore, the NL team in the best position to mount a left-handed attack. (As if Dodgers fans needed another reason to root against San Francisco.) Should the Dodgers win the pennant, they could run into one of two tougher challenges: the Rangers (Cole Hamels, Martín Pérez) or the Red Sox (David Price, Eduardo Rodríguez), who ranked second and fifth, respectively, in percentage of batters faced by lefties during the regular season.

Up until this point, we’ve been treating the Dodgers’ disaster season against lefties as indicative of their underlying skill. Now it’s time to draw an important distinction: Just because the Dodgers have been historically bad against lefties in 2016 doesn’t mean that they are historically bad against lefties. Platoon splits — particularly in matchups against lefties, which yield smaller single-season samples — fluctuate dramatically from year to year. Many of the Dodgers’ left-handed hitters — including Adrián González, Chase Utley, Joc Pederson, and Josh Reddick — have been far worse against lefties this season, relative to their work against righties, than they have across their careers or in the recent past. Even right-handed hitters such as Justin Turner and Howie Kendrick have been much more productive against same-handed arms. We would never expect a team that’s been as good as the Dodgers against righties to stay so inept against lefties; over large samples, splits that enormous don’t exist in the wild.

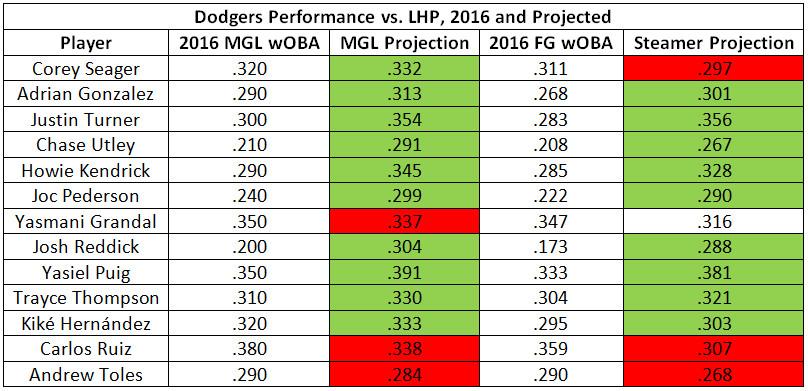

To get some sense of how good against lefties the Dodgers actually are, I contacted two people who forecast hitters’ performance by pitcher handedness: Mitchel Lichtman, coauthor of The Book: Playing the Percentages in Baseball, and Jared Cross, creator of the Steamer projection system. Lichtman and Cross use past performance and regression toward the mean to estimate players’ true talent more accurately than we could by taking their 2016 splits at face value. In the table below, I’ve listed each statistician’s assessment of the most-used Dodgers hitters’ actual 2016 performance and projected future performance, expressed in weighted on-base average, or wOBA. (Lichtman calculates wOBA differently from FanGraphs and Cross, so I’ve included both versions.) If the forecast expects a player to hit worse against lefties going forward than he has this year, the projected value is shaded in red; if the forecast foretells an improvement, the projected value is shaded in green.

Some of the actual and projected values differ significantly between the two methods, but the takeaway from both systems is the same: There’s much more green than red. Of the 13 players on each list, only three per — including the two who’ve had the least playing time in L.A. — aren’t projected to be better against lefties in the future. In other words, what’s appeared to be an Achilles’ heel might not be worth worrying about.

Lichtman’s projections paint the Dodgers as a roughly league-average-hitting team against lefties. While it’s very unlikely for an average true-talent team against lefties to be as bad against them as the 2016 Dodgers by chance alone, it’s not impossible. And even if the Dodgers aren’t quite as good as the projected stats say, they’re almost certainly not as bad as they’ve been. For the Dodgers, that green-shaded future needn’t wait until 2017 to take shape; Friday in D.C. would do.

Thanks to Mitchel Lichtman, Jared Cross, and Zach Kram for research assistance.