On a team with the league’s flashiest manager, the most heavily covered executive in the game, the likely MVP, last offseason’s most expensive free-agent bat, and the reigning Cy Young winner (who is also an underwear model), you’ll find Kyle Hendricks, the model of consistency.

In 30 starts this season, the 26-year-old Cubs right-hander has made it through five innings 30 times. He’s allowed four runs or fewer 30 times, and he’s posted a game score of at least 40 30 times. Nobody else in baseball can say the same. Sure, he’s got a couple of 12-strikeout games and a complete-game shutout tossed in there, but Hendricks led the majors in ERA not because of a string of spectacular starts, but because he went the whole year without getting lit up once.

“Watching him on a start-by-start basis has been fascinating, because pretty much every start he’s got the command and the same stuff every time out,” said Cubs manager Joe Maddon. “You would think that a guy would, at some point, have a difficult outing. Even when he’s not 100 percent right on, his ability to throw something soft for a strike in a fastball count really helps him in certain moments against aggressive hitters.”

Previously a league-average starter, Hendricks has become one of the best pitchers in baseball. But to achieve that level of unmatched consistency, he had to become unpredictable.

Hendricks looks like his fastball in the way that people sometimes look like their dogs; at 6-foot-3, 190 pounds, he’s tall without being intimidating and lean without being skinny. His only remarkable physical attribute is his shockingly deep voice. Unlike Jake Arrieta, the hard-throwing Texan whose muscles have muscles, or the gigantic Jason Hammel, Hendricks just looks like a normal dude, with a normal fastball to match. As a result, he’s been compared (as is always the case when a righty with good command but an iffy fastball has any success) to Cubs great Greg Maddux.

Except in his prime even Maddux threw harder than Hendricks does.

Among 73 qualified starters, Hendricks is tied for 58th in average fastball velocity, with Bartolo Colón. Hendricks’s four-seamer sits around 90 miles per hour, which is borderline suicidal for a right-hander in a hitters’ park. It’s at best his third-best pitch, but Hendricks is atop the ERA leaderboard because he’s throwing it almost three times as frequently as he was last year.

“The best pitch in baseball is a well-located fastball,” said Cubs catcher Miguel Montero.

Hendricks doesn’t have elite velocity, but “well located” is something he can do. And even though he doesn’t throw gas, his ability to throw what he wants where he wants when he wants has turned into a weapon in and of itself. When calling pitches, Montero treats it like one.

“I don’t have the gas, but I have the location,” Montero said. “So as a catcher I still call my game. I still call what I think is the best game for him stuffwise.”

“Not everyone has the command,” said former teammate Dan Haren. “I think that’s what separates people. You can have the best game plan in the world, and you can know exactly how to get hitters out, but if you can’t execute the pitches and put them where you want to, it really doesn’t matter.”

Nobody knows that better than Hendricks, who’s been tagged since childhood with what might be the single greatest backhanded compliment for a guy in his line of work: “pitchability.”

“I haven’t had the electric stuff since I was young, so I’ve always had to be able to pitch,” Hendricks said. “I knew command was going to have to be my game. Learning command takes a while, though — up through the minor leagues that was my whole focus.”

Hendricks was a standout at Capistrano Valley High School in Mission Viejo, California, enticing the Angels to spend a 39th-round pick on him out of high school. But Hendricks turned down not only the Angels but the two-time defending WCC champion University of San Diego (which would years later produce Hendricks’s teammate Kris Bryant) in favor of the freezing cold and relative baseball obscurity of Dartmouth College in New Hampshire.

“Where I was at in my development, I couldn’t see myself sitting for a year, or even two,” Hendricks said. “If you go to a big program, you might not play your first two years, and I didn’t know what that was going to do to me.”

Hendricks got his wish, earning second-team All–Ivy League honors as a freshman. He struggled as a sophomore, but bounced back to post a 2.47 ERA and a .236 opponent batting average as a junior. The Texas Rangers picked Hendricks in the eighth round in 2011, only to deal him and minor league third baseman Christian Villanueva to the Cubs a year later for the aging Ryan Dempster. Hendricks made his big league debut in 2014 and posted a 2.46 ERA in 13 starts as a 24-year-old rookie. But his lack of elite velocity always made it feel like a matter of time before big league hitters would figure him out.

It almost happened in 2015. This time last year, Hendricks was relying on his two best pitches — his sinker and his changeup — almost to the exclusion of his four-seamer and his curveball.

“Last year I was a two-pitch pitcher,” Hendricks said. “Part of that is that my mechanics didn’t feel solid, so I didn’t have a lot of confidence when I was taking the mound. But it’s pretty much impossible to be a two-pitch starter in this league, particularly if you don’t have electric stuff.”

Mechanical issues are scary for a pitcher — getting off-rhythm or losing your release point can lead to a loss of command or velocity, serious injury, or even the yips. It’s what derailed Tigers righty Jordan Zimmermann’s recovery from a neck injury this year and possibly cost Detroit a playoff berth. Hendricks never got that bad, but he still had to fight to keep his delivery together.

“It’s really frustrating. I was struggling with it for maybe a month or more,” Hendricks said. “It’s going to happen in this game. You’re not going to be perfect all the time, so when you go through those bad things, you learn a lot about yourself — basically, different cues or checkpoints in your delivery. So hopefully, if it happens again in the future, maybe you can get out of it quicker.”

Last year, Hendricks was just fine in spite of those limitations, posting a 96 ERA+ in 180 innings, with 8.4 K/9 and 2.2 BB/9. But because he didn’t feel confident in his fastball, he was limiting his options.

Hitting a baseball isn’t just about tracking and reacting to a pitch; it’s about game theory — guessing, to a certain extent, because when a baseball takes a third of a second to get from the rubber to the plate, hitters just don’t have the time to think through every possible scenario and react. Hitters use scouting reports, the game situation, and common sense to create a mental map of probabilities, so instead of preparing for every pitch in every location in every count, they can narrow the list of possibilities down to a manageable number before the pitch. Many pitchers push back against this by throwing harder or releasing the ball closer to the plate, and therefore reducing the batter’s reaction time, but Hendricks doesn’t have the physical gifts to pull that off.

A relief pitcher will see a hitter only once per game and a few times per season, so he can get away with having just two pitches, but if a starter is going to the same two pitches in mostly the same spots over and over, hitters are going to figure them out by the third time through the order.

“Last year I thought he fell into patterns too much,” Montero said. “So first time through the order, he was good. The second time through the order was a little bit tougher, and the third time through the order — he needed to be on to get through it.”

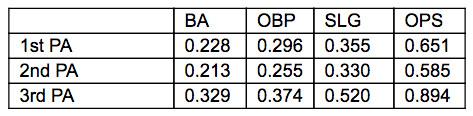

This is Hendricks’s 2015 opponent batting line by time through the order:

Just like Montero said, Hendricks could fool hitters twice, but after that they went from hitting like Adeiny Hechavarria to hitting like Mookie Betts.

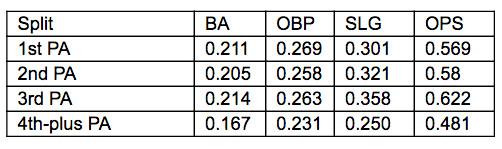

“This year instead of being so predictable, I’m using my four-seam more, I’m pitching inside better, and I’m using my curveball,” Hendricks said. “Using two pitches in my repertoire a lot more than I did last year and pitching inside more — those two factors together opened up a lot for me in terms of margin of error when I do decide to go to my go-to pitches.”

That actually might be understating it. Every pitcher and pitching coach in the Western world talks about controlling the strike zone, commanding both sides of the plate, and being able to throw any pitch in any count, but very, very few can actually do it. Throwing the curveball and four-seamer more doesn’t just add two more things for a hitter to worry about; between location and deception (how can you tell the four-seamer from the sinker until it breaks?), the hitter now has to identify one pitch and one location out of dozens of possibilities. That’s a lot to think about in a third of a second.

“He doesn’t really repeat a sequence with a batter,” Montero said. “I think that’s the biggest thing he’s done this year.”

Here’s Hendricks’s times-through-the-order split for 2016:

“[Hendricks] can throw something in a fastball count other than a fastball and still be very sharp with his location,” Maddon said with a playful smirk. “And hitters don’t like that.”

Because of all the hoopla about Chicago’s farm system under Theo Epstein, and the money they’ve spent, and their 103–58–1 record this season, the Cubs are expected to win the World Series this year. It’s absolutely unfair to expect that from any team before the playoffs even start, let alone one whose last title is closer in time to the Holy Roman Empire than it is to the present day.

But that’s nonetheless the expectation for Hendricks, Arrieta, Jon Lester, and John Lackey, who will almost certainly make up the deepest rotation in the 2016 postseason. Last year, Hendricks made two lackluster playoff starts and took a pair of no-decisions as Maddon pulled him from both before anyone could get a look at him a third time, but this year he’ll have an opportunity to be a more integral contributor. Depending on how you define an ace, as many as six teams in this year’s playoffs — the Cubs, Dodgers, Giants, Red Sox, Rangers, and (if and when Stephen Strasburg comes back) Nationals — will be able to call on two of them. Hendricks could make the Cubs the only team with three.

Maddon and the Cubs will expect a great deal from Hendricks this October. Opposing hitters, on the other hand, won’t even know where to start.