Race Is the Past and Future of Horror Movies

Forget ghosts, zombies, and witches. The realities of black life would make for the scariest movie you’ve never seen.Welcome to Future of Movies Week. Too often this year we’ve been left baffled at the multiplex, resembling the thinking-face emoji. It’s been 10 months, and we’re struggling to come up with a viable top-10 list. Streaming platforms are encroaching on Hollywood’s share of our collective attention, preexisting intellectual property is providing diminishing returns, and moviegoers largely skipped Jack Reacher: Never Go Back. Wild days.

November will be different. It’s packed with interesting releases — Oscar contenders like Loving and Arrival and Manchester by the Sea, blockbusters from Marvel (Doctor Strange) and J.K. Rowling (Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them), a Disney movie with Lin-Manuel Miranda and the Rock (Moana), and old-fashioned fare from big-name directors like Robert Zemeckis (Allied) and Warren Beatty (Rules Don’t Apply).

This week, we’re looking at the future — of film school, horror, the Marvel Universe, movie stars, and the medium itself.

Every Halloween for the past 20 years, LaRethia Haddon, a grandmother from Detroit, has decorated her lawn with a dead body. A dummy, actually, that she dresses up, mucks with fake blood, and displays in front of her house. Her homespun gore has gotten so realistic over the years that she’s had to preemptively warn the police, as frightened passersby have been known to report the fake dead.

This year, her grandchildren suggested something different. "They said, ‘Children aren’t afraid of the boogeyman anymore,’" she recently told CBS News. An anonymous Law & Order–style corpse no longer cuts it: Real life is worse. This October, the bodies in front of her house bear signs: "CARJACKED." "STOP KILLING OUR CHILDREN." There’s a scientist holding a jar of "Flint water." There’s a corpse on her porch outfitted in a hoodie and jeans, arms skyward: "MY HANDS WERE UP." It isn’t just the grotesquerie of Haddon’s designs that’s unsettling. It’s what those bodies mean, the waves of violent, real-world context that crash into view when we see them — on an occasion like Halloween, no less, typically a night to commemorate the unreal, not the everyday.

There remains much to be said for the specificity of our everyday terrors — for the difference between Haddon’s bodies and the two stuffed dummies hanged from nooses in front of a home near Miami. Our run-of-the-mill social fears are partially the calculus of who we are, and when, and where. We aren’t all from once-bankrupt industrial cities in the American heartland, like Haddon, who calls the collection of death on her lawn "our reality." Whose reality? We don’t all face threats of sexual violence, police brutality, or the political negligence of poisoned drinking water with equal likelihood or vulnerability.

Art can illuminate the contingencies of those terrors — even, apparently, on Halloween. Horror, the genre known for slashers, ghouls, and possessed baby dolls, could be reimagined as a response to the real-world horrors of something like racial violence. What’s a ghost or a sulfur-breathing ghoul compared to the everyday fears cataloged on a Detroit grandmother’s front lawn? The latter are subjects typically earmarked for melodrama or realism, or for pulpy crime movies whose supposedly realistic grit distracts us from their mere escapism. We don’t typically think of horror as morally serious. It’s creepy and yucky, and it pushes our limits and plays on our primal fears and instincts. But its connection to the real world is meant to be intentionally slight: The theater is where we leave that world behind.

Recent history has reminded us that racial terror makes for an effective freak show, as anyone following the cycle of police shooting, to protest, to grand jury acquittal already knows. H.P. Lovecraft once wrote of the difference between "mere physical fear" and "cosmic fear": the difference between being grossed out and, in the cosmic extreme, of having one’s sense of how the world works upended. True horror is cosmic fear. It’s there when I pass by cops at night, or when there’s a Confederate flag waving from the truck of a customer in the same restaurant as me. Horror, as Lovecraft described it, beckons "unexplainable dread." Keyword: unexplainable. Racism is no mystery. But whether it’s in store, at any given moment, certainly is.

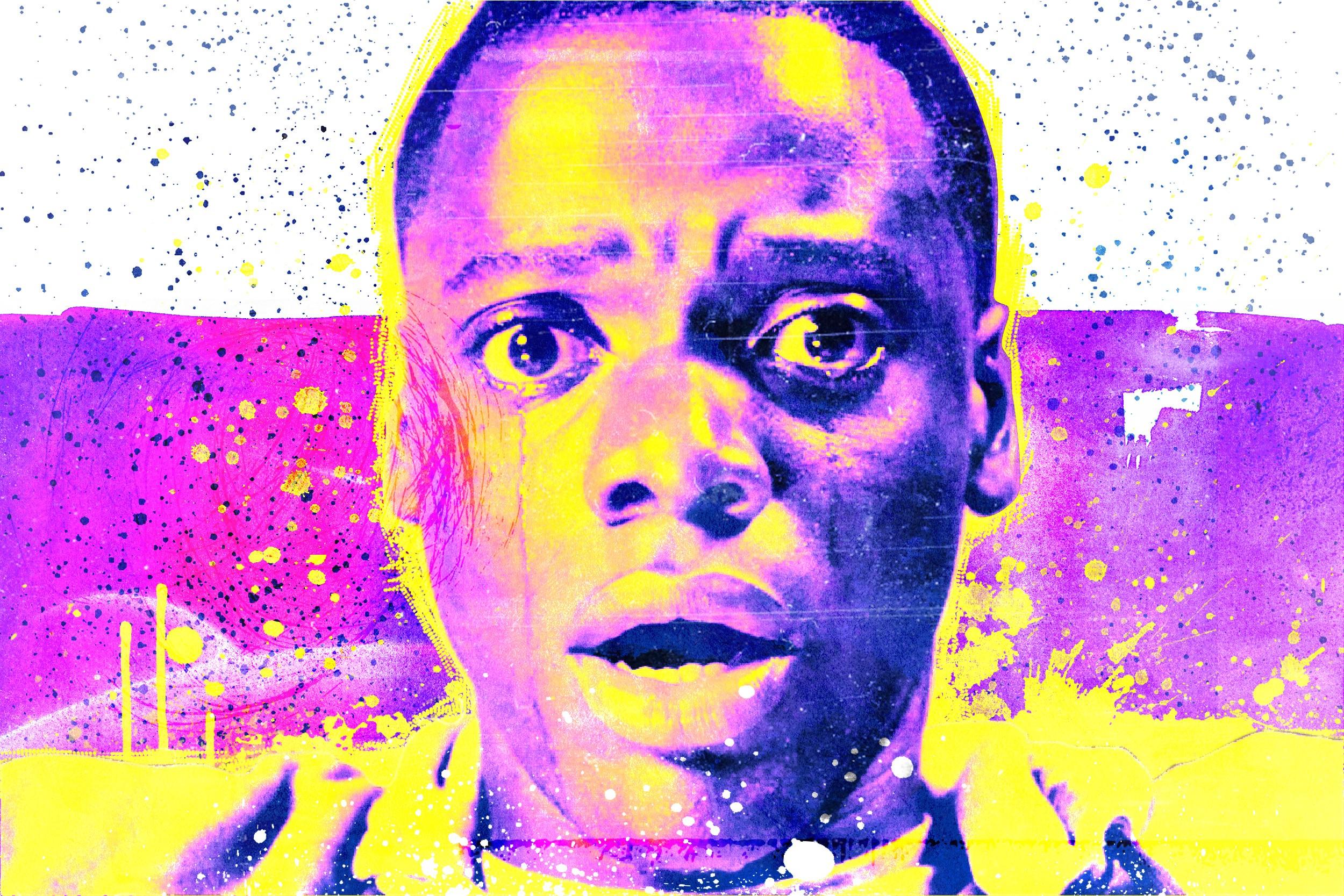

That’s enough to convince me that race and horror shouldn’t be so at odds. Horror is resurgent at the box office — this year especially. Yet, somehow, amid #OscarsSoWhite and other pushes to diversify Hollywood, the genre has largely remained the province of white artists and their white protagonists. Earlier this month, though, comedian and horror aficionado Jordan Peele, formerly of Comedy Central’s Key and Peele, released the first trailer for his upcoming directorial debut, a horror film titled Get Out. It stars Daniel Kaluuya as a man going to meet his white girlfriend’s parents for the first time: Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, but — if the trailer is any indication — retold through one black man’s inner terror. It isn’t a movie about the perils of the hood, or of the overt racism at a Trump rally, but — even weirder — the terror of middle-class white people. (Peele is ever the comedian.)

Peele’s movie has already generated excitement as that rare thing: a horror film explicitly about blackness. He told Playboy in 2014 that the film will be "one of the very, very few horror movies that does jump off of racial fears. That to me is a world that hasn’t been explored."

In fact, that world has been explored — just not like this.

"Why don’t white people just leave the house when there’s a ghost in the house?" joked Eddie Murphy in 1983’s Delirious. "Very simple: If there’s a ghost in the house, get the fuck out."

It’s a well-known, oft-told bit of cultural logic about blacks in horror movies: We don’t seem to stick around. Either we have too much sense to go exploring the unknown or we die early on (though not usually first). We’re never the final girl. There’s a bit of condescension in this absence, a hint of: Don’t black people already have enough problems?

Well, yes, and attempts at black horror narratives often acknowledge as much. But they’re also a chance to play with style. The 1995 hood thriller Tales From the Hood wielded horror as a tool for social parable — Scared Straight!, but spookier, and funnier. Michael Jackson’s corpse glamour in "Thriller" is as much a tribute to Jackson’s fluid virtuosity as a performer — he could be anything, even the undead — as it was an exploration of the horror genre, which Michael loved. There was the blaxploitation era, with vampire tales like Bill Gunn’s indispensable experiment Ganja & Hess (1973) and the classic Blacula (1972). Toni Morrison’s Beloved (1987) and the 1998 Jonathan Demme movie it inspired draw from the spooky, ghost-ridden Southern Gothicism of slave narratives and William Faulkner to excoriate the evils of slavery by way of a baby ghost.

The work of horror, it has been argued, is to uncover what a repressive culture like ours would hope is dead and buried. But as far as public discourse is concerned, black culture — more often being repressed than doing the repressing — doesn’t have room or patience for fantasy. What’s a black ghost? A slave — obviously. Outside of comedies, the black-led films that seem to get the most attention deal with the supposed reality of blackness — grit, violence, historical suffering, the melodramatic breakdowns of black families: the Moynihan Report as cinema. Imagine The Sixth Sense — which is set in Philadelphia, well known to have predominately black, often-crime-ridden neighborhoods — with a black boy at its center. Would the movie have to somehow address his urban reality? Would there have to be a ghost with a gun wound? Would the hanged ghosts he sees toward the end of movie, who are all white in the original, have to be black, for the sake of continuity?

It seems like a silly thought experiment. But horror films about and not merely inclusive of black people have already tended to lean on historical pain, rather than the present. Think back to Wes Craven’s The People Under the Stairs (1991), in which a black family is terrorized by their landlords, an incestuous brother and sister who are clear riffs on the Reagans. Or Samuel Fuller’s White Dog (1982), in which a woman finds a beautiful stray dog that, she learns, had been trained by its previous owner to kill black people. Or Jacques Tourneur’s haunting I Walked With a Zombie (1943), which is set in the Caribbean among descendants of slaves who try to cure a white zombie woman with voodoo.

Think back, most of all, to the 1992 movie Candyman, which is in many ways an exemplary exploration — and refutation — of how blackness has had to function in a horror film. It has a white heroine named Helen (Virginia Madsen), a researcher in Chicago who studies urban legends. While gathering stories for her thesis, she becomes fascinated by the tales of a hook-handed ghoul known as the Candyman. The Candyman is a dashing but terrifying black man who haunts the once-infamous Cabrini-Green housing projects. The well-educated son of a slave, he was a talented portraitist who made the mistake of falling in love with one of his subjects, a white woman. He’s punished for it: His hand is cut off, he’s stung to death with bees, and his corpse is burned. When the movie opens, he’s an established part of the lore shared by the black residents of Cabrini-Green — a present menace.

Until Helen shows up. The movie makes a point of marking Helen as a figure of black displacement. The building she lives in, originally intended to be the sister structure Cabrini-Green, was instead fashioned into expensive condos for educated whites; yet, as she notes, the outlines of the buildings are the same. In a way, what happens to Helen comes off in the movie as karmic punishment — for being white. She isn’t merely hunted by the Candyman: He possesses her body and has her kill on his behalf, causing a ruckus in the Cabrini-Green apartments that attracts police attention to the detriment of the black residents. He exacerbates her privilege. She becomes their nightmare.

Race is a horror story. The bodycam footage of black death tells me that; old images of lynchings tell me that. The fabricated fears of suburbanites, the stuff horror is made of, afflict blacks in real time — and there is the rub. Confronting race in a horror film would mean confronting, and troubling, the idea of a white protagonist. Who, but a white person, would be the villain of a black horror movie? Candyman is not subtle, but as an inversion of both the historical trope of black men possessing white women’s bodies and the horror trope of the heroine whose survival is preordained, it’s a thrilling road map for what horror films about race can do. The Candyman is the villain — but Helen is not the hero. If it’s race we’re dealing with, there may not be one.

Much of the prestigious art by and about black Americans lately traffics in the horrors of race while resisting becoming horror, the genre, outright. The recent flush of slavery films has sometimes borrowed from horror movies’ ability to dissociate themselves from reality. Steve McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave occasionally found ways to make slavery seem like a heightened unreality. The best moment in Nate Parker’s The Birth of a Nation used the color-saturated light from a stained glass window to make the initial murders in Nat Turner’s rebellion sing with a weirdly horrific spiritualism.

Horror could be the way to make black pain present again. It seems crass to ask that one of the most traumatic realities of modern black life be folded into horror films, but they are already keen tropes of black drama, melodrama, and comedy. The nuances of black life get cut down to a few familiar rites of passage — police encounters, for example. By the time we get to a movie like the N.W.A biopic Straight Outta Compton, in which interactions with the LAPD are meant to establish formative moments that would become the substance of the young artists’ work, director F. Gary Gray barely has to work to dramatize these incidents. We know what the cops will do, how the black heroes will feel; we know the routine. The director has to do only so much. We can rely on our cinematic memories, and our own lives, for the moment to have power — hence the moment gradually being emptied, over time, of its immediacy. Now, it’s a meme.

The future of horror can and should be one in which race amounts to more than a historical past. History is, of course, useful: It could explain a black character’s evil, or flesh out why the world might seem terrifying to a black protagonist. But black skin doesn’t, out of necessity, always need to carry with it the entire history of black trauma. Horror films can be aggressively presentist, topical, even satirical: It Follows — in which "It" is the cops. An unarmed black citizen’s death wrenched into a murder mystery. Single White Female for black girls.

The thrill of Get Out is that it seems ready to take that risk. The movie looks stylized and unsettling, off-kilter to the point of even being — go ahead, you can say it — bad. There’s a fine line that Get Out will have to walk, beholden as it is to the serious demands of its politics and to the rules of a genre some may think is at odds with its subject. It’s also a chance to show us what horror can do that prestige pictures, with their plainer moral attitudes, cannot. That’s why it’s escapism: a chance to escape from realism and the real, alike. This time, the black guy might actually make it to the end.

An earlier version of this piece incorrectly identified the lead actor in Get Out; it is Daniel Kaluuya, not Keith Stanfield.