In 1979 the Chargers released their fight song, “San Diego Super Chargers,” the only anthem as confident in its team as it is in the power of disco. It feels like it was recorded as a jingle to advertise a sale on shag rugs at the local carpet emporium, but was co-opted for sports at the last second. If you grew up in San Diego, like I did, the song is probably etched into the deepest recesses of your mind, prone to emerge at inopportune times. (Perhaps when a cashier says, “The charge didn’t go through,” and you respond, “Chargers CHARGE!”) Somewhere along the way, an updated, modern cover was released and then abandoned. People insisted on the old version.

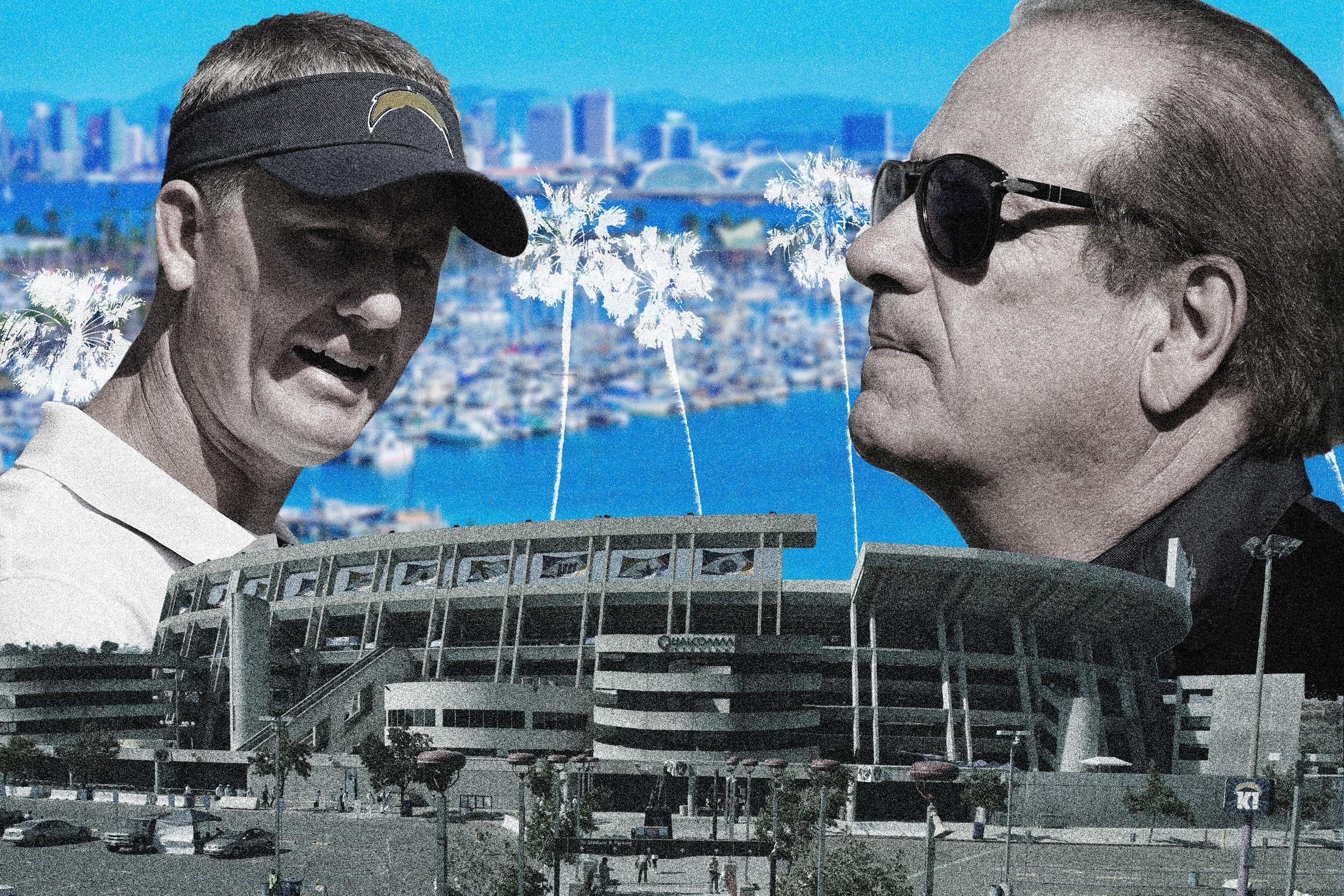

The irony is that, in order to stay in San Diego, a franchise locked in a perpetual state of nostalgia now needs to promise the future: a sleek, straight-out-of-a-sci-fi-blockbuster “convadium,” the bloated municipal love child of a convention center and a stadium. In November, San Diego will vote on whether to build the Chargers a new stadium using more than a billion dollars sourced from a proposed hotel tax increase; if the measure fails, it’s likely that Chargers owner Dean Spanos will march the team north to Inglewood. Outsiders sometimes assume that San Diego won’t care if the Chargers leave, equating the failure to vote for a billion-plus-dollar convadium with a lack of civic pride. In reality, attempting to connect civic pride to stadiums is a misguided narrative that feels tired in 2016.

Proposing to keep the Chargers in San Diego by leaning on taxpayers for a billion dollars is a nonoption disguised as an option. The convadium is being advertised as “free” because a hotel tax would charge tourists, not San Diego citizens. But that logic doesn’t account for what might happen to the economy if the tourism industry suffers because of higher costs, or to the local residents, whose general-budget money would be reallocated if the hotel tax fails to raise more than a billion dollars. It’s a plan devised without reality in mind, reminiscent of what would happen if the Hardy Boys meticulously diagrammed their ideal clubhouse.

The franchise’s demands are particularly damning at a time when it feels like we get annual reminders that publicly funded stadiums jeopardize cities while failing to deliver the promised economic gains. Last year, St. Louis lost the Rams but inherited the debt of an NFL-less arena. This year, it could be San Diego’s turn. The situation epitomizes the purgatorial existence of the Chargers fan base. The tradition of watching Chargers games is akin to saying: Stay with us until the very end, and we will not only lose, but we will do so in spectacular fashion. The stadium proposal follows the same logic: Remain loyal to us after we tried to ditch San Diego for Carson, and we will not only demand public money, but we will demand a cartoon-villain amount of it.

Ballot measures of this nature tend to work best coming off the blind euphoria of a championship. Or a winning season. Or at least a game without a “laugh to keep from crying” fourth-quarter meltdown. Former San Diego mayor and current chamber of commerce president Jerry Sanders made the case for a new home for the Chargers by explaining, “For us, it’s also a matter of civic pride, and the positive impact a new stadium would have on the East Village, Downtown, and the entire region.” But “civic pride” isn’t effective when it’s trotted out as a rhetorical device that’s meant to inspire, because the sentiment is most palpable when it’s threatened. That’s why Joey Bosa’s mom using Facebook to say, “Wish we pulled an Eli Manning on draft day,” was the most simple, yet incisive way to get the city’s attention: San Diego will never get over the embarrassment of the 2004 draft and the memory of Eli Manning flashing his this-family-vacation-makes-me-want-to-die smile.

Shortly after the draft, Manning appeared on Late Show With David Letterman. The host asked: “Now were there other teams that you said ‘I’m not interested in playing for’?” Manning shook his head before Letterman could finish the question and replied, “No, that was the only one.” Letterman laughed, Manning laughed, everyone laughed! The entire debacle made San Diego puff out its collective chest; civic pride emerges when residents seek to avoid that kind of laughter, not when bureaucrats use it as a fundraising crutch.

I find that it often feels like critics use the city of San Diego as a lens through which to understand the Chargers’ weaknesses — lazy! Too much sun! Head in the clouds! — but I see the opposite: The Chargers’ stadium turmoil is the best way to understand San Diego. It is the second-largest city in California and eighth-largest in the United States, yet it continues to struggle to define itself outside of the weather and Anchorman references. Instead, San Diego is characterized by sweeping generalizations — “America’s Finest City,” “a bland, happy place” — the way politicians combine words to form platitudes that fail to say anything at all.

Cries to unite the sprawling city under one stadium feel especially hollow in light of real signs pointing to its identity crisis. The number of people leaving San Diego outpaces the number of people moving to San Diego. The city’s tech industry is growing and wants to become “the next Silicon Valley,” but can’t seem to retain developing companies; startups that mature move north, just as the Chargers intend to do. Living in San Diego has become a pitstop on Americans’ “I’m Busy Finding Myself” tour, but rarely the final destination.

San Diego was once home to a music festival called Street Scene. The lineups were always all over the place — one year featured Kanye West, Tool, Bloc Party, and Sean Paul — but also anticipated a time when this type of programming would become the norm. Street Scene — which predated Coachella — developed before music festivals became an industrial complex, their monotony becoming a parody of copycat lineup announcements. After the festival’s 25th anniversary in 2009, it shut down, citing debt and low attendance.

I think about Street Scene often in the context of the Chargers, especially whenever people joke that San Diegans are too busy hanging out at the beach to get their shit together. Good ideas develop in San Diego, sometimes even ahead of the trend, but it’s a difficult environment for them to thrive in. If and when the Chargers leave San Diego, one of the inevitable story lines will be that San Diego didn’t work hard enough to keep its team. But ultimately, voting to build Spanos his billion-dollar Barbie Dreamhouse shouldn’t be necessary to demonstrate how much fans care. When faced with rising costs in an already expensive city, San Diegans find it damn near impossible to show they care about anything.

The Street Scene website still says, “We’ll be back.” If November’s ballot initiative fails, the Chargers won’t bother making the same promise.