A 10-Tool Player Is Dominating the Postseason

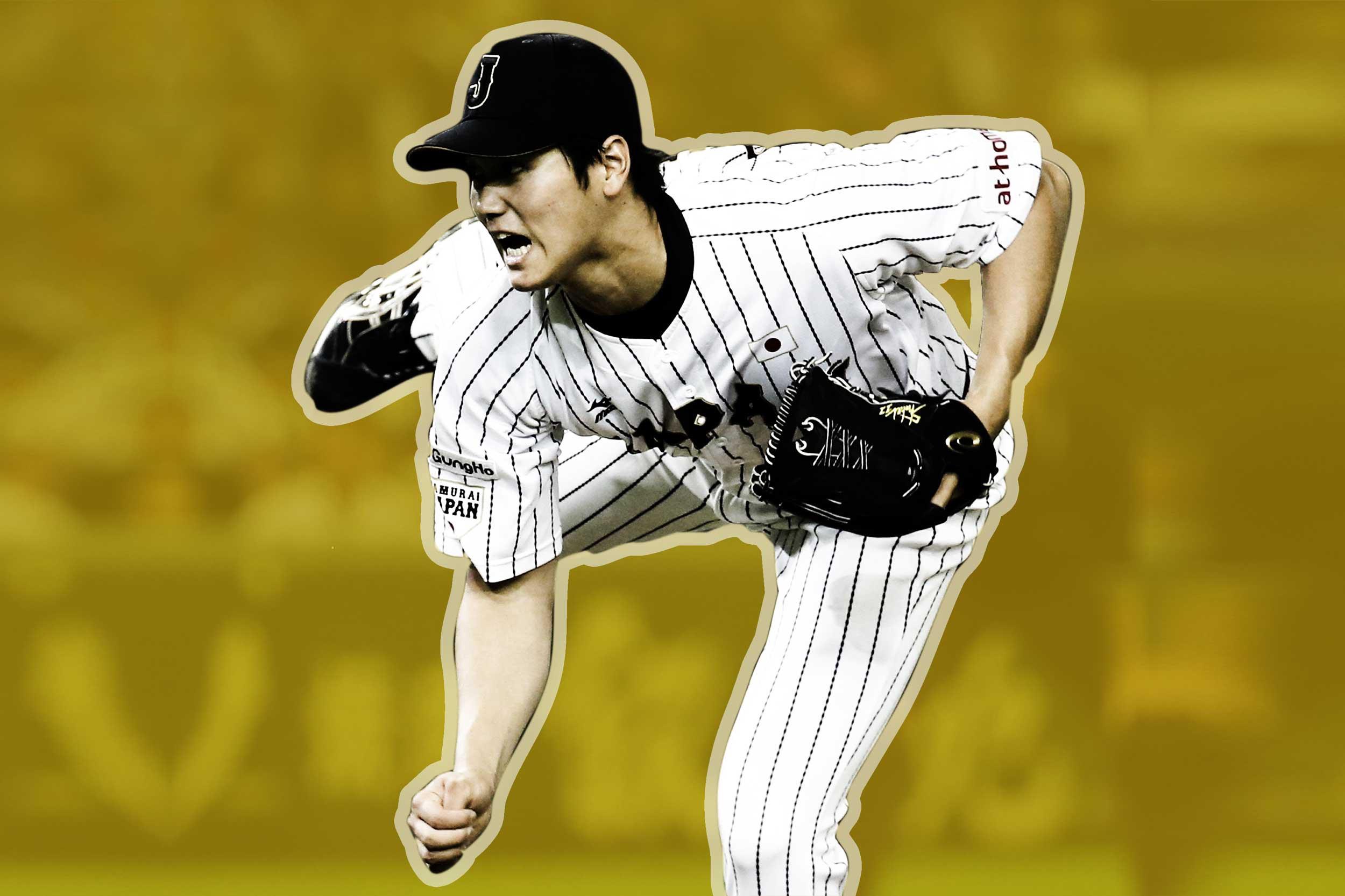

Just not the postseason you’re watching. Shohei Otani is a sports superweapon who’s owning Japan’s NPB as a hitter and pitcher alike, but if the 22-year-old decides to head west, will an MLB team have the courage to let him try to be a two-way star?With apologies to Javier Báez and Andrew Miller, the most impressive postseason performance of 2016 is taking place 4,300 miles away from the nearest MLB ballpark. On Sunday in Sapporo, Japan, in front of 41,000-plus fans, Shohei Otani, the best starting pitcher in Japanese baseball, did something that would have broken the baseball internet had it happened here. He got a save.

It was Otani’s first career save, but that undersells its significance. This save, which sealed the semifinals of the "Climax Series" — Japan’s perfect term for the playoffs — sent Otani’s team, the Hokkaido Nippon-Ham Fighters, to the Japan Series, a seven-game showdown between the winners of the Central League and the winners of the Pacific League. In his one inning of work, Otani retired three consecutive hitters from the Fukuoka SoftBank Hawks, the two-time defending Japan Series champions. In the process, he threw two fastballs 165 kilometers per hour — 103 miles per hour, to those of us still spurning the metric system. That broke the NPB record of 164 he’d set in September, which broke the previous record of 163 he’d set in June.

In the same outing, he also threw 89 mph sliders and a 94 mph forkball, which inspired this cartoon depiction of Otani as a Pokémon trainer, with a Magikarp marveling at how hard he throws his off-speed stuff.

Please hold your applause: It gets much more impressive than that. Four days earlier, Otani had started the first game of the series and thrown seven scoreless innings, allowing only one hit and two walks to the team with the Pacific League’s highest on-base percentage. Not bad, but we’ve seen MLB aces masquerading as closers as recently as last week. What sets Otani apart even more than his arm is his hitting.

Before he came in to close, Otani had already made four trips to the plate as Hokkaido’s designated hitter. He also started at DH in the three games he didn’t pitch. And he took his turns at bat in Game 1, as he often did on days he pitched during the regular season, even though the Fighters have to surrender their DH for him to pitch and hit. That leaves them with a weaker lineup when he exits the game, but several innings of two-way Otani is worth the sacrifice: In addition to his eight shutout innings, Otani reached base at least once and scored in every game of the Climax Series.

Otani’s 2016 performance produced the most climax-worthy stats page since late-career Barry Bonds. In 140 innings, he struck out 174 and allowed only four home runs, finishing with a 1.86 ERA — an improvement on his 2015 performance, when he’d been one of the top three contenders for the Sawamura Award, Japan’s equivalent of the Cy Young. While he was at it, he hit .322/.416/.588 in 382 plate appearances, launching 22 home runs. And to top things off, he won the Home Run Derby.

Essentially, this season Otani boasted Noah Syndergaard’s stuff, Clayton Kershaw’s ERA and strikeout rate, and David Ortiz’s OPS. And just to show that there was no hole in his game, he stole seven bases in nine attempts. He’s so good that he’s forcing officials to change the rules: Thanks to his hitting, pitchers are now eligible to win a Best Nine Award — Japan’s Silver Slugger — at DH.

Advanced stats don’t diminish what Otani accomplished. According to Deltagraphs, a Japanese-language subscription site that publishes sabermetric stats for NPB players, Otani led NPB with 10.4 wins above replacement — 4.6 as a hitter and 5.8 as a pitcher. That combined total is roughly equivalent to Mike Trout’s single-season high.

There’s an unseen asterisk on Otani’s eye-popping stats, just as there was with Bonds’s: Otani plays in a quadruple-A league. According to ESPN’s Dan Szymborski, who created and maintains the ZiPS projection system, the performance of players who’ve relocated across leagues suggests that NPB’s quality of competition is approximately one-third of the way from Triple-A to the majors. That would put its difficulty level somewhere between 85 and 90 percent of MLB’s, which means that Otani’s rate stats are somewhat inflated from facing inferior players.

On the other hand, Otani’s fairly limited playing time makes his WAR even more amazing. Otani was a 10-win player even though the NPB plays a 143-game schedule — about 12 percent shorter than MLB’s — and even though he served almost exclusively as a designated hitter for two months at midseason, when a blister on his right middle finger (that seemingly wasn’t related to his double duty) prevented him from pitching. And then there’s his age: Otani turned 22 in July. If he makes the move to the majors and continues to be a two-way regular (more on that in a moment), it’s plausible that a combination of better health, a longer schedule, and physical and mental maturation could help him make up in value what he’d lose as a result of the league’s higher difficulty level.

Otani could fall pretty far and still be a stud. In Japan, he’s a giant, and not only because his broad-shouldered, 6-foot-4 frame means he physically towers over most of his teammates.

According to Deltagraphs, the average four-seamer in the Pacific League this season was 88.8 mph, almost 4 mph slower than in the majors. Otani’s 96.2 mph average was nearly 5.5 mph faster than the closest full-time Pacific League starter’s. Only five regular MLB starters bested Otani’s average, and based on how easily he was able to touch triple digits when he wanted to, it seems safe to assume that Otani would have had a higher average if he’d been facing more hitters who’d forced him to dial it up. NPB is the world’s second-best baseball environment, and Otani makes it look like Little League.

Otani allowed the second-lowest percentage of pulled balls (26.5 percent) among NPB pitchers with at least 90 innings, which indicates that NPB hitters had trouble getting around on his heat. He induced the fourth-highest out-of-zone swing rate, and he recorded the lowest contact rate by an enormous margin: The difference between Otani’s contact rate and the second-lowest was as big as the gap between the second-lowest and the 29th-lowest. Otani’s park-adjusted run average and FIP were the best in Japanese baseball, and his xFIP was second best. And on a per-pitch basis, the righty had the best curveball, the third-best four-seamer, and the third-best slider in Japan. Everything he threw was filthy.

There’s a little more cause for concern about how his offense would translate to the States. Based on his surface stats, Otani was as dominant at the plate as he was on the mound: The lefty swinger batted .375 with seven homers in 96 at-bats against left-handed pitchers. Deltagraphs says he was 82 percent better than the average Pacific League hitter this season — significantly better, relative to his league’s average, than any qualified major league hitter in 2016. He was the fourth-best hitter against four-seamers, on a per-pitch basis, among hitters with at least 300 plate appearances, and he was also above average against sliders and curves, so it wasn’t as if he could be beaten by breaking balls. Otani wasn’t a free swinger — he finished eighth in the league in walk rate, with only two intentional passes — but when he did offer at pitches, he wasn’t just trying to put the ball in play. Instead, he swung like a power hitter, finishing with NPB’s 10th-lowest contact rate, right around those of imported power sources such as Brad Eldred, Wladimir Balentien, and Brandon Laird.

Opposing pitchers treated Otani with the respect due to a slugger. Only 35.0 percent of the pitches he saw were inside the strike zone, NPB’s fourth-lowest rate — just behind all-time single-season home run king Balentien’s 34.9 percent. And that’s where the concern comes in: Wladimir Balentien is Japan’s all-time single-season home run king. As in, the Balentien who slugged .374 in three major league seasons and seemed destined to keep bouncing between the big leagues and high minors until he went to Japan and developed superpowers the way Superman did in the rays of our sun. Otani ranked eighth among NPB hitters (minimum 100 at-bats) with 14.7 at-bats per home run, but NPB power doesn’t translate to the majors the way other skills do. Szymborski says that singles hitters suffer almost no penalty when they move from NPB to the big leagues, but for power hitters, the drop-off can be even bigger than it would be after a promotion from Triple-A. It doesn’t help that Otani had a .396 batting average on balls in play, NPB’s second-highest figure (min. 300 at-bats), which hints at some regression in store (even though he also ranked 12th in hard-hit rate).

In addition, while Otani has been a beast on the mound for three seasons, he doesn’t have quite the same history of superstar-level success as a hitter. Although he hit 10 home runs in only 212 at-bats in 2014 — which caused him to say he was "about 50 percent (satisfied)" — he sandwiched that campaign between two offensive seasons that stood out only by pitcher standards. We know, though, that hitters and pitchers improve and decline at different rates: Hitters tend to make gains until they reach a peak in their mid-to-late 20s, whereas pitchers often see their results fall off as their arms accumulate innings and their velocity dips. The same likely goes for Otani the hitter and Otani the pitcher, even though they’re the same guy. Otani worked on his hitting mechanics last winter and also added almost 20 pounds of muscle while training with former Fighters ace Yu Darvish, which may have contributed to his breakout year at the plate. Babe Ruth wasn’t so hot as a hitter at age 21, either. (Yes, I just dropped a Babe Ruth comp.)

The question, of course, is when we’ll see him in the States, and not just via pirated Japan Series streams. Otani is under contract with the Fighters through 2019, although there’s reason to think they’ll relinquish control before then. Unless the current posting system changes, the Fighters can collect only a $20 million release fee, and any team that meets that fee would be free to negotiate with Otani. Kyodo News reporter Jim Allen wrote last month that "the Fighters have tried to persuade their stars to stay, but have not stood in their way and will likely post Otani should he request it." Otani is earning a little less than $2 million this season, which ties him for 25th in NPB. That’s a big number for a player his age, but Japan’s salary ceiling is fairly low; this year’s highest-paid player, Hiroki Kuroda, is making only three times what Otani is. Otani came close to signing with the Dodgers straight out of high school, so we know he’s amenable to the idea of following in Darvish’s footsteps by heading to the States. And were he to jump even younger than Darvish did, with his stock as high as it is now, Otani could command 10–15 times his current salary.

Despite the allure of international stardom and a huge hike in pay, there’s no indication that Otani’s exit is imminent; Allen believes he won’t move on until after he pitches (and hits!) for Japan in the World Baseball Classic next year. However, there is a scenario with an outside shot of bumping up the timeline. "If he manages to win MVP and also the Japan Series this year, perhaps things could get interesting," Japan Times writer Jason Coskrey says. At that point, Otani would have little left to prove in NPB. Coskrey adds that he’d "be surprised if [Otani] didn’t" win the MVP, both because Otani deserves it and because the award tends to go to a player on a pennant-winning team. (Although the voting is supposed to be based on regular-season performance, the ballots aren’t due until after the Climax Series.) If you’re looking for a rooting interesting over the rest of the month and you aren’t into MLB’s four remaining teams, pull for the Fighters to take down the Hiroshima Toyo Carp. Game 7 would be played on October 30 in Japan, and MVP voting results will likely be announced in late November.

When Otani does request to be posted, we’ll find out whether MLB teams are willing to indulge our (empirically derived!) dream of a two-way star. "I think it’s a great story and hope he can pull it off, but the history of non-Ichiro, non–Hideki Matsui hitters coming from that league isn’t great," one AL scout told me. "Most recently two league MVPs in [Tsuyoshi] Nishioka and [Hiroyuki] Nakajima came here and were fringe Triple-A players. That’s not to say it’s impossible. He’s dominating in a pretty good league and that counts for something."

It’s not certain that other NPB teams would have allowed him to hit; the Fighters, Coskrey told me on a podcast about Otani in July, are "not the most conventional team," and their manager, Hideki Kuriyama, is "a little bit eccentric." The Fighters are known for taking risks, including drafting Otani, who had already expressed his opposition to staying in Japan. It would take another unconventional major league team to give Otani a chance as a full-time two-way player.

Given how protective teams are of young pitchers, it would take a brave GM and manager to test Otani in the field and on the bases instead of playing it safe and using him exclusively as a (very valuable) starter. However, Otani stayed in Japan in part because the Fighters offered him the chance to keep hitting, and he’ll be reluctant to leave without a similar guarantee. Every MLB team will want Otani, but the one that lands him will probably be the one that believes the most in his two-way potential, both because that will make Otani most enticing to them, and because it will make them most enticing to Otani. If an AL team signs Otani, he’d have a harder time hitting on the days he pitches, but he could continue to DH as he’s been doing. If an NL team signs Otani, he’d have to play the field on his off days as a pitcher — which, because he’s a freak, he’s capable of doing, although that would subject him to much greater strain. Coskrey told me that when Otani struggled at the plate in 2015, fans and media members criticized him for not concentrating on his pitching; if he does pursue the two-way path in the majors, we can expect more of the same at the first sign of a slump on either side of the ball.

Dave DeFreitas, who scouted Otani in Japan for the Indians and the Yankees, acknowledged in a recent report that Otani’s arm is ahead of his bat, but he also projected Otani as a future all-around average everyday right fielder in the majors if he’s allowed to hone his defense. (DeFreitas also projected him as a top-of-the-rotation starter, and that was before most of his 2016 dominance.) "He just has a cannon for an arm, and he read balls off the bat really well," Coskrey said, based on Otani’s play in the outfield corners for the Fighters prior to 2015. "He was a really good outfielder, and if he’d kept doing that, he probably would’ve become a great outfielder." DeFreitas graded Otani as a 70 runner on the 20–80 scouting scale, which is truly unfair given the rest of his skills. If we could describe anyone as a 10-tool player, it would be Otani.

Otani might never be more fun than he is right now, when he’s coming as close as any player conceivably could to carrying his team to a championship. Reality will have a hard time competing with the vision we can construct: not the borderline type of two-way player who’s hardly hanging on in either role — Micah Owings, Brooks Kieschnick, Drew Butera, Rafael Betancourt — but one of the best pitchers in baseball, whose bat also happens to make Madison Bumgarner’s look like Bartolo Colón’s. Five years ago, José Abreu was slugging almost 1.000 in Cuba, and with no way to know what his weaknesses were, we were free to focus on his strengths. Then we learned what Abreu actually was: very good for one year, pretty good the next, and by Year 3, just kind of OK — no longer fodder for daydreams. Otani’s talent isn’t as much of a mystery as Abreu’s; we can dissect his stats and watch him for hours whenever we want. The mystery lies in whether any team will be willing to do the difficult thing: risk routine greatness to chase a sports superweapon we might never see again.