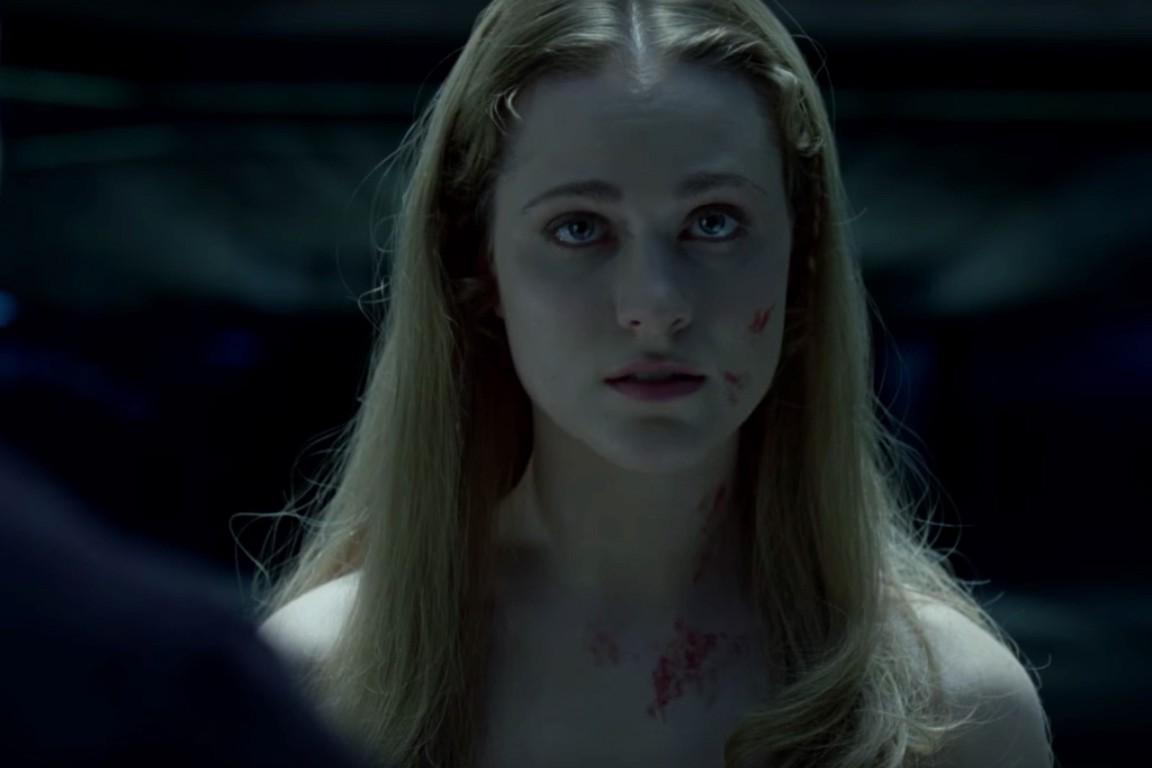

The first episode of Westworld opens with a creepy, disembodied male voice interrogating a naked lady robot.

“Do you know where you are?” the voice asks.

“I’m in a dream,” Dolores says.

“Would you like to wake up?” the voice asks.

“Yes,” she says. “I’m terrified.”

Luckily for Dolores, she’s about to be sent back to her equally harrowing day-to-day life, which involves getting repeatedly raped in the Wild West theme park where she lives in a ranch house. She only has to answer one question correctly:

“Have you ever,” the voice asks, “questioned the nature of your reality?”

“No,” Dolores says.

Then she’s back in bed, and the sun’s streaming in through the windows. It’s another lovely day to go out and paint landscapes. But whether she’s dreaming or not, the question of her reality comes back to haunt her.

A young boy, for instance, visiting the park with his parents, leans in to Dolores and whispers:

“You’re one of them, aren’t you? You’re not real.”

Dolores blinks blankly, which is how she’s meant to react. The androids in Westworld are programmed to unquestioningly perform the role of themselves for the benefit of human “visitors,” who pay through the nose to interact with them in whichever way their human hearts should desire. Usually, it seems, their hearts desire to have sex with the androids or murder the androids, though also there are times when they just want to wander around and muse about the nature of the androids’ existence.

And since we, too — as members of the show’s audience — are paying visitors of the park, we’re invited to ask the same questions. How real, for instance, are these robots? They have material bodies; they pair off into couples. They drink milk; they beg not to be murdered. Does the fact that they’re programmed make them less real than we are? Is it excusable that we sit by and watch them get raped because their minds are electronic simulations of human consciousness, and not the real thing?

These are questions we’re accustomed to: It’s common for science fiction that features artificial intelligence to ask us to consider what makes a living consciousness. As our technology continues to advance, how can we be sure our computers aren’t sentient? And how do we excuse the way we use them to our own ends if there’s a possibility that they are?

Westworld takes the questions further than this. We’re not just meant to wonder about the nature of robots’ reality; we’re also meant to wonder about the nature of our own. The show is set in a future in which disease has been eliminated; human DNA has been tinkered with. The scenario reminds us that we — like the park’s robot hosts — are products of DNA programming, whether or not it has been updated by human scientists. And does the fact that we’re programmed, too, make us less real than we like to imagine?

The question of our fundamental reality is one that Elon Musk, founder of SpaceX and cofounder of Tesla Motors, recently asked — or, actually, pretty confidently answered — by proclaiming that there’s a “one in billions chance” that we’re not living in a computer simulation right now. Musk’s ideas about artificial intelligence and alternate realities are important because he’s innovating at the forefront of both movements. This spring he and his partner unveiled their new artificial intelligence company, OpenAI, and on September 27 he outlined SpaceX’s plan to colonize Mars. You can almost imagine his AI-powered colonies on the red surface of Mars looking something like Westworld headquarters.

“I’ve had so many simulation discussions it’s crazy,” he said at the Code Conference in June. “It got to the point where every conversation was the AI/simulation conversation, and my brother and I agreed that we would ban such conversations if we were ever in a hot tub … because that really kills the magic.”

Musk made the hot tub point twice, and it was pretty telling. “It’s not the sexiest conversation,” he said, giggling a little, the assumption seeming to be that women in hot tubs, like naked lady robots, do not like to question the nature of their reality, preferring (as everyone knows they prefer) to think about simpler subjects, like bubbles. In any event, his point is that our lives — whether women find it titillating or not — are less real than realistic. “The strongest argument,” he said, “for us being in a simulation, probably being in a simulation, is the following: 40 years ago we had Pong, two rectangles and a dot. That is what games were. Now 40 years later we have photorealistic 3-D simulations with millions of people playing simultaneously and it’s getting better every year. And soon we’ll have virtual reality, augmented reality. If you assume any rate of improvement at all, the games will become indistinguishable from reality.”

“Even,” Musk went on to say, “if the rate [of advancement] drops by a thousand from right now — imagine it’s 10,000 years in the future, which is nothing in the evolutionary scale. So given we’re clearly on a trajectory to have games that are indistinguishable from reality and those games could be played on a set top box or on a PC or whatever and there would be billions of such computers or set top boxes, it would seem to follow the odds we’re in base reality is one in billions.”

The basic question at the core of Musk’s simulated universe hypothesis — whether or not we’re really living in the real world — has been around for centuries. Musk is adapting an idea published by the Oxford philosopher Nick Bostrom in 2003, and wondered over by zillions of stoned teenagers since long before Musk or his brother ever climbed into a hot tub.

In fact, the philosophical puzzle dates all the way back to Plato’s allegory of the cave. In the allegory, Plato likens people to prisoners chained in a cave, all facing the back wall. Behind them, there’s a puppet show playing, but they can only face one direction, so all they know of the puppet show are the shadows of puppets cast on the stone. Because they can’t turn around, these benighted people think the shadows are the real objects, not simply reflections, and when they talk about “puppets,” they’re sadly missing the point: They’re trying, and failing, to grasp a reality just out of their reach. The idea is that what animates our world hovers somehow just out of view, or just beyond comprehension, so we’re forced to stumble around with a sense of vague and frustrating unknowing.

Throughout much of the pilot, Westworld’s androids seem happy to admire the shadows. They behave, at first glance, like Elon Musk’s idea of women in hot tubs. When the little boy tells Dolores she isn’t real, she blinks and changes the subject. When her father finds a photograph of a woman standing in Times Square, Dolores takes one look and walks away. “It doesn’t look like anything to me,” she drawls. The idea that there might be a puppet master just over her shoulder is — or seems to be — a question she’s not concerned with.

But then again, thanks to a new round of updates, other hosts are starting to get it. Dolores’s father puzzles over that photograph until he suffers an android psychic break. By the end of the first episode, we know that Dolores is capable of lying to her interrogator, so when she says again that she doesn’t question the nature of her reality, we know enough to guess that she might. And since — in a twist that does, admittedly, feel a little simulated — Elon Musk recently tweeted that his ex-wife “does a great job of playing a deadly sexbot” in future episodes of the show, it seems reasonable to expect that the naked lady robots of Westworld are only getting more annoyed with the unpleasant cave they’ve been chained in.

Their programmers have caught the same bug. For instance, take this conversation on the show between a manager from the corporation behind Westworld and a writer who designs the experience:

“I know,” the writer says, “management’s real interest in this place goes way beyond gratifying some rich assholes who want to play cowboy.”

Management’s representative is icy in her response. “You’re smart enough to know there’s a bigger picture,” she says, “but not smart enough to guess what it is.”

By the end of the first episode, we’re in the same position as the writer. We know there’s a bigger picture, but we don’t quite get what it is. So the humans in Westworld, and the audience of Westworld, are also chained in the cave, concentrating on the shadows of puppets, unable to turn around and see the real puppet master. This kind of plotting — there’s an Oz behind the curtain, but it won’t be revealed for a long while yet — is typical of big, world-building shows like Westworld and Lost. But this show, in particular, asks us whether or not we’re willing to accept a situation in which we’re being controlled by a force we can’t see and don’t understand.

Westworld’s androids are in a bad situation, and the implication is that our situation isn’t too different. The show asks us — along with Dolores and the head writer — to question the nature of our reality. We can’t say we’re real because we’re not programmed: Like the androids we’re watching, we are. And we can’t say we’re real because we comprehend reality in its whole scope: Like the androids we’re watching, we don’t. What, then, makes us more real than an android? And what makes our world more real than a theme park for gamers?

For the robots in Westworld, that’s a disturbing possibility. By the end of the first episode, it’s clear that they want to run their own lives. Not being permitted to do so causes them to have meltdowns and go on killing sprees. Elon Musk, on the other hand, seems to be willing to accept life as a mere simulation: He says, in fact, that “we should be hopeful this is a simulation,” since the alternative is that future technological advancement has ceased.

Maybe Musk can accept the idea that his entire existence was switched on by some Silicon Valley wunderkind because he is a Silicon Valley wunderkind. Or maybe he’s just contented to know that whoever is playing him is playing so well: In the Rick and Morty virtual reality simulation game (in which visitors at Blips and Chitz put on a headset and guide a simulated man through the quotidian events of his life), Musk is clearly being operated by Rick, who takes his simulation off-grid, not Morty, whose simulation beats cancer only to go back to work at the carpet store.

As motivation to accept a simulated reality, there’s always that age-old reward for the sacrifice of free will: In Musk’s game version of life, if you murder an android, it’s not really your fault. You weren’t the one pressing the buttons. Also, even if you did murder the android, who really cares, since there’s always the overwhelming probability that in some other simulated reality you didn’t murder the android and can therefore go on existing as an innocent, non-murderous person. As Rick once told Morty, “There’s pros and cons to every alternate timeline.”

Or maybe Musk just accepts simulation as the preferable of two wretched possibilities. As he explained at the Code Conference, our simulation guarantees the steady pace of technological progress: As long as the human race hasn’t been wiped out, our games will continue to advance, which means (according to Musk) that we aren’t in “base reality.”

Putting aside the questionable nature of arguments based on trajectories of progress, the conclusion Musk draws is also questionable — it’s based on the premise that we live in a world composed of discrete reality levels, like “base reality” and “simulated reality.” We don’t. The images on a computer screen are just as real as the computer, which is just as real the person playing on the computer. We’re all made of the same stuff. You could argue that nevertheless only one of the three has real consciousness, but then again, we don’t really know what consciousness is, so that’s a hard call to make, and one I’d rather not risk, since the task of picking and choosing who’s conscious is one we haven’t exactly aced as a species. By having slaves, for instance, or committing genocide.

The concept of levels of reality is questionable, but what I find even more disturbing about Musk’s particular vision of the future is how neat it is: how rule-based and how ordered. His future games are the product of progress. Even if we aren’t at the controls, someone is. His vision precludes the idea that our realities bump up against one another and disturb them, that life can be messy and disordered, that there are no hermetically-sealed plotlines.

Which is what makes Westworld as a concept more interesting than Elon Musk’s simulations. Because everywhere you turn in Westworld, the divisions between realities are breaking down. The story lines are bleeding together. Dolores may say she doesn’t question the nature of her reality, but she’s probably lying. When her father quotes Shakespeare, it’s possible he understands what he’s saying.

These robots have turned around in the cave. They sense a puppet master and they want to face him. They’re looking over their shoulders, and the puppet masters behind them are looking over their shoulders as well, and it’s starting to seem as if the strings have been cut.

My guess is that, in Westworld, it’s about to get pretty hard to decipher who’s real and who isn’t, and whether that word has any meaning to start with. No one in the show seems to be paying attention to the boundaries between realities, much less to rules passed down from above on what’s appropriate to discuss when a naked lady ends up in hot water.

Disclosure: HBO is an initial investor in The Ringer.

Louisa Hall is the author of the novel Speak.