This year’s MLB standings, which are now set in stone, appear to have two tiers: the one that contains the Cubs, and the one that includes everyone else. The Cubs finished with a division lead nearly twice as large as any other first-place finisher’s, and they’re the only team to top 100 wins; every other division winner has a comparatively pedestrian victory total between 91 and 95.

Really, though, there are three tiers: the one with the Cubs, the one with the Red Sox, and the one with everyone else. You just have to squint to see the second tier.

On the surface, the Sox are, if anything, AL underdogs, at least among the teams with division titles. Boston has the fewest wins and smallest margin of victory of any AL division winner. The Indians edged them by one win despite the Cleveland pitching staff’s late-season losses, and the Rangers will have home-field advantage throughout the playoffs by virtue of their league-leading win total and the AL’s All-Star Game victory.

But even though baseball’s regular season is really long — on Opening Day, Taylor Swift and Tom Hiddleston were still a month away from meeting — it’s not quite long enough for every team’s true talent to shine through. To gauge that, there’s third-order record, a Baseball Prospectus stat that strips out some of the largely non-skill-based factors that influence team performance.

You know about run differential and Pythagorean record, which capture how effectively a team has outscored its opponents. By those measures, Boston has been baseball’s second-best team, and the AL’s best by seven wins, too much to hand-wave away as the product of beating up on bad pitching in blowouts. Third-order record, though, takes two additional steps that run differential and Pythagorean record don’t. First, it strips out the effects of a team’s timing on offense and defense, so that the team won’t get extra credit for clutchness or be penalized if, like this year’s Sox, it has lousy cluster luck. (Of course, clutchness matters in a retrospective sense; it’s just not something that teams have, on the whole, shown the capacity to repeat.) Second, it accounts for quality of competition, which matters for a team like the Red Sox, who played almost half of their schedule against a division that produced two other playoff teams and three other teams with winning records.

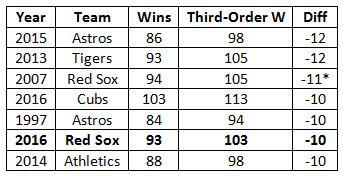

On average, playoff teams in the expansion era (1961–2016) have outplayed their third-order regular-season records by two wins. That makes sense; sometimes, qualifying for the postseason takes a little luck. It’s more common, then, for playoff teams to exceed their third-order records by big margins than it is for them to fall far short. This year’s Red Sox are just one of seven playoff teams in the past 55 years to underperform their third-order records by 10 wins or more. Boston’s been on this list before — and that team won the World Series.

You’ll notice that the Sox aren’t the only 2016 team on the leaderboard. As impressive as the Cubs’ actual record is, their superior third-order record offers even more reason to think that they’re the best team in baseball and the justified favorites to win the World Series. But the Sox can stand up to anyone else. Their third-order record tops any other AL team’s by 10 wins. And based on Boston’s current depth chart, Baseball Prospectus gives the Red Sox the league’s best expected record (exclusive of schedule), as well as baseball’s second-best chance to win the World Series, with more than double the championship odds of any other AL team.

Now, here comes the caveat: The playoffs are extremely tough to predict, and many a smart statistician has tried and failed to find the hidden factor that finally lets us stop saying “crapshoot.” In the wild-card era, third-order winning percentage has essentially the same weak correlation with postseason winning percentage that actual regular-season winning percentage does. Why? Well, maybe because of sample size: The whole wild-card era encompasses fewer than 700 postseason games, most of them played between teams that were roughly evenly matched. Maybe it’s that regular-season records, whether third-order or actual, are produced over a span of six months, whereas postseason performance is a snapshot of what a team is today. Or maybe it’s that the playoffs’ off-day-filled format allows teams to construct their rosters and deploy their players in ways that they couldn’t during the regular season, which further erodes our predictive powers. We could theorize that for the few teams at the extremes, such as the Sox, third-order record would be more predictive than actual record. But there haven’t been enough outliers like them to establish whether that’s so.

Without an answer key to October, we pay attention to small edges while largely relying on what we’ve learned during the long lead-up to postseason play. That means picking the teams that showed themselves to be better over the previous six months, unless they’re limping into October shorthanded or running into opponents that figure to benefit more from the freedom to hide back-end arms. And Boston’s AL opponents all appear to have even higher hurdles to clear.

The Blue Jays and Orioles have to win a coin-flip faceoff to advance to the ALDS. The Indians’ rotation is injury-riddled. The Rangers have outperformed their third-order record by 16 wins, more than any other team on record, thanks to historic clutchness and an incredible record in one-run games — another aspect of performance that’s proven almost impossible to sustain. (The Red Sox are 20–24 in one-run games, even though good teams tend to win them more often than not.) The Rangers outscored their opponents by only eight runs on the season, and while they made major midseason additions, their opponents have outscored them by one run since their first game with Jonathan Lucroy in the lineup. The Rangers’ defiance of the usual way to win makes them one of this season’s best stories, but it doesn’t mean the magic will last.

The Sox, meanwhile, have had the American League’s best offense, led by a likely MVP winner (Mookie Betts), the best 40-something hitter ever, and two other veterans, Dustin Pedroia and a revamped Hanley Ramírez, who’ve spent the second half hitting about as well as they ever have. They’ve led the league in performance versus finesse pitchers, and they’ve led by much more against power pitchers, who become more common in October. Successful comebacks from injury (Craig Kimbrel, Koji Uehara), trade additions (Brad Ziegler), and long-awaited conversions (Joe Kelly) gave them one of the game’s most unhittable bullpens down the stretch. They lead AL playoff teams in Defensive Runs Saved, and they’re the league’s second-best base runners. Their rotation, which is widely seen as their weakness, ranks sixth in the majors in both Deserved Run Average and park-adjusted ERA, and while it suffers from the absence of breakout star Steven Wright and midseason trade acquisition Drew Pomeranz, it’s not so thin without them that the rest of the starters can’t keep the offense in games.

Put it all together, and the 93–69 Sox look like the AL’s most probable pennant winners. Unfortunately for Sox fans, that means only so much: In baseball, even the team to beat will probably be beaten.

Thanks to Rob McQuown of Baseball Prospectus and Rob Arthur of FiveThirtyEight for research assistance.