For a moment there, Jill Soloway’s Emmy speech teetered toward train wreck. Transparent’s creator and frequent director — she was collecting the award for helming “Man on the Land,” the penultimate episode of the show’s second season — ended her address with a rallying cry of “Topple the patriarchy,” a slogan that also contains the name of her production company, Topple. Earlier, she’d thanked Amazon’s Jeff Bezos for “invit[ing] me to do this thing that these people call television, but I call a revolution.” The statement verged on the self-aggrandizing, particularly when delivered to a tech billionaire in a room full of television professionals. And “revolution” sounds less like good art and more like an additional burden to the already formidable task of storytelling.

But the third season of Transparent proves that the show is a revolution, and not just in the political vein that Soloway is so often active in. Transparent is an artistic revolution, too, in the way that it reinvents how we talk about those political issues. The two aspects of the show exist hand-in-hand. Soloway’s beliefs aren’t awkwardly grafted onto her work; they’re deeply embedded into it.

Since Transparent debuted in 2014, a consistent hype cycle has followed Soloway’s work. Soloway broadcasts her ambitions to work toward female, queer, and trans liberation with her art; those ambitions seem impossible to translate into a narrative that’s not weighed down by its own mission statement; the final product pulls off the balancing act without apparent effort. It’s something of a TV miracle: Transparent is idealistic but never ideological. And as Soloway’s output verges on expanding into an entire slate of Amazon shows, there’s every sign that she plans to make this balance into a signature.

In August, a test case arrived in the form of I Love Dick, the pilot that Soloway directed based on a script from playwright Sarah Gubbins (itself based on Chris Kraus’s sorta-novel). On paper, the idea of Soloway adapting I Love Dick was both so ambitious and so on-brand it bordered on self-parody. A theory-heavy cult novel about reclaiming feminine hysteria, among other Gender Studies 101–friendly themes, I Love Dick made for an extremely unlikely show. Add in a New York magazine preview in which Soloway declared, “I don’t know how to write about anything other than myself … I only want to write about somewhat unlikable Jewish women having really inappropriate ideas about life and sex,” and it was easy to see I Love Dick as a bridge too far — an overextension of Soloway’s powers into the clunky, a self-inflicted trigger of the critical backlash that’s always one misstep away for any celebrity, feminist figureheads especially.

The actual pilot, starring Kathryn Hahn as flailing filmmaker Chris Kraus and Kevin Bacon as the titular love object she latches onto, is … not that. For one thing, the first episode is viciously funny, an aspect of the source material Kraus herself has long argued is underappreciated. And given that Amazon will almost certainly order more episodes to further cement its relationship with Soloway, the rest of the show will be similarly outrageous. “I think both the characters in the book are just hilarious,” Gubbins tells me, referring to Chris and her academic husband, Sylvére. “They’re emotionally messy.” Emotional messes are what Soloway does best.

Hahn, Soloway’s unofficial muse (she starred in Soloway’s 2013 debut feature Afternoon Delight and acts on Transparent), plays Chris’s motormouth neuroticism as equal parts ridiculous and rational. When she explodes at Dick’s trollish suggestion that female filmmakers simply aren’t very good — “Sally Potter! Jane Campion! CHANTAL AKERMAN!” — she’s both a sputtering stereotype and reasonably upset. We understand both halves of Chris; we’re allowed to laugh at her even as we’re indignant on her behalf. It’s a marvel of character building, the same feat Transparent pulls off with each member of the Pfefferman clan. That trick of character building is how Soloway communicates her more high-flying ideas: She buys goodwill for knotty concepts like the female gaze by gently ribbing their most out-there applications.

Soloway literally embodied this approach in Transparent’s first season, when she made a cameo as a professor insisting “It’s feminist to audit!” By Season 3, perennially aimless youngest Pfefferman Ali (Gaby Hoffmann) has dived headfirst into grad school, only widening the show’s favorite, and easiest, target. The season’s most go-for-broke sequence results from the ill-advised combination of two equally mind-altering substances: laughing gas and too much Judith Butler.

But Soloway’s evolving onscreen relationship with feminism and its many forms mirrors her relationship with her characters: Her ability to mock them emerges from her love for and connection to them. It’s no coincidence Season 3 finds a newly woke Ali addressing her prayers to the Goddess, just like Soloway does. Soloway is able to poke a character like Chris, who proudly declares the protagonist of her film “kind of represents all women and society’s crushing expectations,” because she’s undertaking a similarly ambitious project. (Gubbins says they chose to bring in additional characters “because the singularity of Chris Kraus as stand-in for all women was gonna be such a heavy burden to put on one character.”) And while Soloway broadcasts that ambition in interviews and awards show speeches — a representative quote from a recent Variety Q&A: “To me intersectionality isn’t one interesting word. It’s everything.” — the actual work follows that oldest grad-school saw: It shows rather than tells.

Which isn’t to say that Transparent never makes its point of view explicit — just that when it does, it fits in comfortably with the rest of the show. Transparent consistently avoids the pitfall of the Teachable Moment, which takes the viewer out of the story and into a nebulous zone between fiction and the reality said fiction is trying too hard to address. It’s allergic to “clapter.”

That’s the point — Transparent comes by its empathy honestly. “I say this a lot, but I do think it’s true: these stories are in our bodies,” says Silas Howard, the show’s first trans director and consulting producer for the third season. “They’re in our DNA. They’re also our lived lives. Because this show really draws from personal experience, I feel like everybody’s personal experience gets thrown into the mix of the fictional story.”

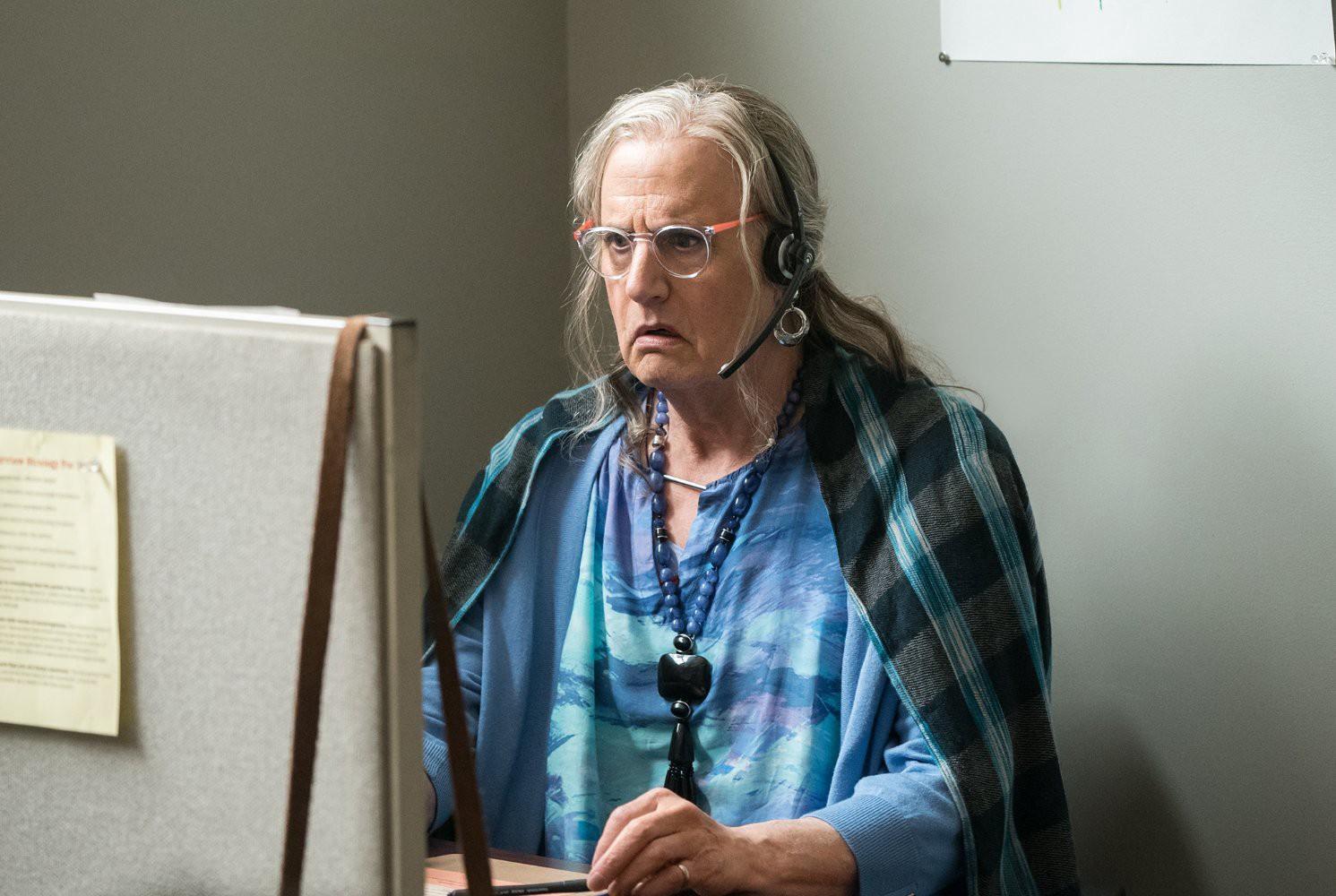

Soloway isn’t afraid to confront the uncomfortable places the story takes her. The entire third-season premiere of Transparent is essentially a parable about white privilege. Two moments stick out. In the first, Maura (Jeffrey Tambor) takes it upon herself to track down a distressed caller to her LGBT helpline in South Los Angeles. The intervention is neither asked for nor particularly welcome, and Maura botches it in spectacular, oblivious fashion, assuming some Latina trans women are sex workers and accidentally shoplifting from a fast food restaurant. It climaxes with Maura collapsing before she can even speak with the caller; Maura’s impulsive trip ultimately wasn’t about the caller, and it never was. The show is similarly damning when it comes to Josh’s (Jay Duplass) whirlwind romance with Shea (Trace Lysette). When she tells him she has HIV, Josh balks at the sudden complication of what he clearly wants to be a distracting fling, and Shea immediately lashes out. “I am a person,” she screams, “and I am not your fucking adventure!” It’s a blunt line, but saved for a situation that calls for it. Later, Josh apologizes by admitting he doesn’t know what he’s doing. This time, Shea’s response is left unspoken: It doesn’t matter.

These moments build on the groundwork laid by the first two seasons, when Maura came to recognize her very real privilege and all three Pfefferman kids were confronted with the smoking rubble of their various relationships. But they also elevate that self-awareness to a level that’s unprecedented on the show, let alone the rest of television.

Tied up as it is in her long-standing interests of gender and shifting identity, Soloway’s distinctly feminine, radically inclusive approach to sex is an ideal showcase for her filmmaking ethos. Soloway has spoken before about the importance of filming sex scenes from the right perspective; two years ago, she vehemently disagreed with Jenji Kohan’s stated M.O. of “My first goal is just get it, and I’ll worry about who’s gazing later.”

The climactic scene of I Love Dick renders that abstract difference — between disregarding and subverting the male gaze — with a pair of erotic encounters, one imagined and one real. The first is Chris’s re-envisioning of her humiliating face-off with Dick as a tryst, and the contrast between the real dinner and Chris’s imagined one is stark. In the first, Dick is both an asshole and the clear victor. In the second, he’s a wordless ideal, there to complete Chris’s fantasy. Later in the pilot, Chris discloses her fascination with Dick to her husband, Sylvére: It’s a quick, dirty conclusion to the couple’s months-long dry spell, less romantic but equally grounded in Chris’s perspective. Apart from a handful of establishing shots, the camera almost never leaves Chris, and keeps Sylvére almost entirely out of the frame. The first scene shows that Chris can exert power over a pretty powerless situation by telling her own story, handily summarizing the thesis of the book. The second shows that even when Chris isn’t narrating, this is still her show.

Transparent, too, upends our expectations for onscreen sex — who has it, with whom, and how. Pfefferman matriarch Maura spent most of the second season negotiating sexuality after her late-in-life transition; eventually, she gets together with Vicky (Anjelica Huston), a cancer survivor and fellow 70-something. Lesbian sex between two aging women, one of whom is trans, is unprecedented on television, but Maura and Vicky’s connection is simple and unabashedly sexy. The show takes people whose sexuality is either fetishized (trans women) or totally erased (older women) and places them squarely on the middle ground where most humans actually live their lives.

This season, the Pfeffermans’ various entanglements run an almost astonishing gamut — gay and straight, BDSM and vanilla, young and old, cis and trans — and the show lets the variety speak for itself. There’s an intergenerational lesbian relationship, modeled on Soloway’s real-life one with poet Eileen Myles. The oldest Pfefferman keeps seeing a dominatrix even after she’s moved back in with her ex-husband. Both relationships are plagued by the same, utterly normal commitment and boundary issues that so-called “normal” ones are, even as they’re electrifying in their specificity. Soloway knows we’ve never seen it before, even on Transparent itself, which has gradually worked itself up to this point. So she knows the mere act of presenting it, without embellishment, is enough.

It’s worth studying not just what Soloway does, but how she does it, because there’s so much more in the wings. She and Gubbins are collaborating once again on Soloway’s second feature, Ten Aker Wood, also for Amazon Studios; it’s about “a woman in a failing marriage who leaves Los Angeles to live on a pot farm in Northern California.” In other words: another concept loosely sourced from Soloway’s autobiography. Her production company’s next project is a musical comedy about “a woman’s search for love and self-discovery in Los Angeles.” There’s a hint of solipsism there, but there was with I Love Dick and even Transparent, too. And the point here isn’t the similarity in plot — it’s the comedy, breadth, and sensuality of Soloway’s work. Besides, Soloway’s just as entitled to repeatedly mine the same material as any other auteur.

Even when Soloway isn’t directly involved, her high profile means that her collaborators are getting work. Howard jokingly describes the Soloway imprimatur as a “golden ticket,” a somewhat amazing turn of events for a filmmaker with such radical subject matter and modest box office results. Howard has done episodic work on Faking It and The Fosters, and a pilot cowritten and co-executive produced by Transparent writers Noah Harpster and Micah Fitzerman-Blue starts production in October. Soloway’s work is beginning to have a trickle-down effect, and as creators from outside the traditional Hollywood pipeline start to get projects made, hopefully its hallmarks will, too. “The truth is, we all deserve to be there,” Howard says. “It’s not that we’re breaking into TV. It’s that TV is breaking into us … It’s not like, ‘Oh, how nice of you, Hollywood.’ They really need some new story.”

The volume of material offers real potential for a defined and widespread sensibility. As Soloway expands from auteur to producer, the question of what makes a Soloway show — as opposed to a Shonda Rhimes show, or a Dick Wolf show — is still very much open. But it has a few calling cards: a strikingly diverse cast of employees, both behind the camera and onscreen, a deeply felt political sensibility — and a set of artistic techniques that allow those values to rise organically to the fore. I Love Dick builds on what Transparent started and is still perfecting, and what future projects will hopefully continue. They don’t lay down their politics by preaching. They find their politics through empathy.