Roald Dahl was writing a book about the White House when he died. That’s not exactly true — he was working on a lot of things then, if your definition of “working on” is “not quite finished yet.” But it was there, tucked away with his other notes and stories and manuscripts, some scribbles on yellow paper and an entire typed chapter devoted to Charlie Bucket’s journey to the District of Columbia. It’s the sort of thing a kid might tell a grown-up. It’ll come together. I’m working on it.

On Tuesday, Dahl, who passed away in 1990, would have been 100. He began writing Charlie in the White House in 1978, midway through the Jimmy Carter administration, intending for it to be the third novel in his Charlie and the Chocolate Factory series. Few writers have had the kind of sustained frenzy around their work that Dahl has, a fascination that’s been particularly pronounced in the years since the release of Tim Burton’s 2005 remake of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. This summer, the latest film adaptation of one of his novels, the Steven Spielberg–directed The BFG, hit theaters.

By now, the worlds Dahl created, their snozzberries and their frobscottle, are familiar to generations of children. Which makes it worth wondering: What would Dahl’s portrayal of the White House have been like? In 1964’s Chocolate Factory, every door in Charlie’s universe — and especially in Wonka’s factory — hid something strange, bizarre creatures or byzantine rules. It’s not hard to imagine how Dahl might have created a similar effect in Cold War Washington, a place where a bombastic, blond-haired, wildly gesticulating real-estate mogul might have felt quite at ease.

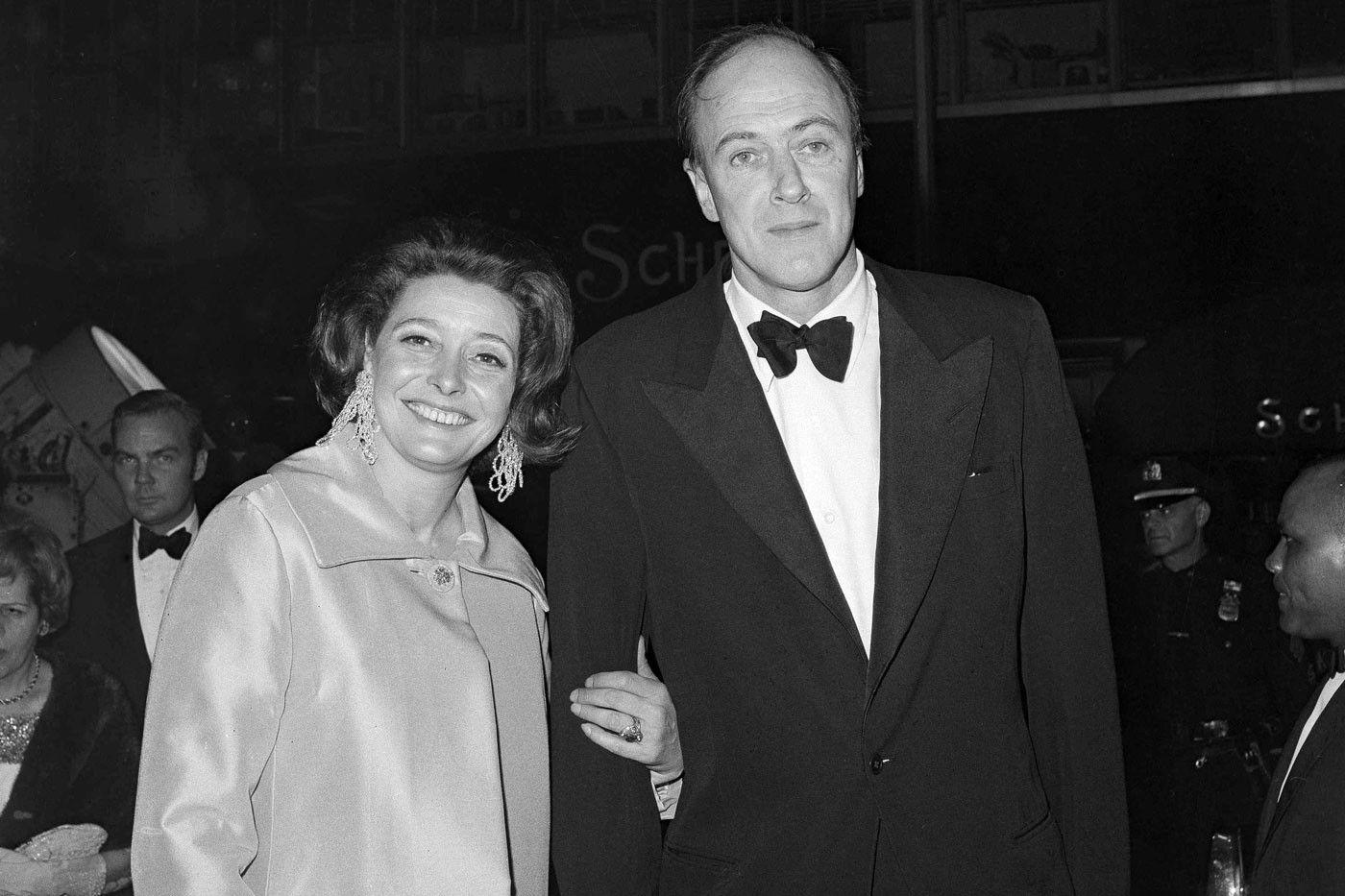

Let’s start by acknowledging that we were robbed of a tale that might have rivaled Dahl’s best. His America was one of spies, Hollywood, and intrigue: After serving in the Royal Air Force during World War II, Dahl was sent to Washington as an intelligence officer, a position he used mostly to inflate tales of his service and meet women, in time earning a reputation as “one of the biggest cocksmen in America.” He bounced between embassies and townhouses, traveled to Los Angeles to consult with Disney on an animated film about the Battle of Britain, and claimed dalliances with everyone from Standard Oil heiress Millicent Rogers to Clare Boothe Luce, a Republican congresswoman known for her anti-Communist views (and her marriage to the publisher of Time magazine), before eventually marrying the actress Patricia Neal.

Dahl’s best work contrasts the wickedness of the grown-up world with the hopeful innocence of children; in little Charlie Bucket and his family, he had the perfect foil. But Dahl’s second book in this series, Charlie and the Great Glass Elevator, never caught on like its predecessor — its weirdnesses were smaller and more ordinary than Chocolate Factory’s, in spite of the story taking place primarily in outer space. The characters spend much of their time in transit in Wonka’s elevator; with little oxygen to lend to new faces, there was only so much room for world-building.

The grand exception to this is Great Glass Elevator’s occasional interludes at the White House, where an oafish president and his vice president/longtime nanny, “a huge lady of eighty-nine with a whiskery chin,” investigate the Bucket-and-Wonka excursion into space. We catch glimpses of the presidential cabinet — a chief financial adviser straining to balance a physical budget on his head; an army chief who is actively trying to start a war — as well as “a sword-swallower from Afghanistan, who was the President’s best friend.” It’s not a great book by any means, but it introduces a cast that could have thrived given time to explore a Wonka-esque mansion with porticos, a situation room, secret chambers, and a basement bowling alley — to say nothing of fanciful space race inventions. (Great Glass Elevator featured the president fretting about the luxury hotel that the American government had just installed in orbit, which risked falling under attack by the Russians, Chinese, Hilton family, or extraterrestrials.)

We’ll never know what Charlie might have found at Dahl’s 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. But considering the tenor of his published works, he might at the very least have found some inspiration in this year’s presidential candidates: a wall hundreds of miles long, to be paid for by a foreign head of state who insists that no such thing will happen; an electorate-wide case of Munchausen by proxy; a crew of staffers inclined to follow direct contradictions with responses like “yes, that’s what I said”; an intense desire for secrecy followed by shock when it raises suspicions; a walking thesaurus of the greatest, best, most amazing, super-classy superlatives. (Dahl’s uglier side — his anti-Semitism and chauvinism, principally — might have led him to find something he liked in that basket of deplorables.)

Consider this portion of Great Glass Elevator’s presidential tune of choice, sung dotingly by the vice president/nanny:

Does this pessimism sound familiar?

Donald Trump has shown an occasionally Dahlian ability to boil very serious grown-ups down to silly, singular villainies: Lyin’ Ted Cruz, Little Marco Rubio, Crooked Hillary Clinton. He paints in bright colors and often appears congenitally incapable of being boring, seemingly toting a magician’s hat filled to some unknown depth with exotic ideas and unsavory personalities. If that sounds like a Dahl character — well, his most celebrated of all was an inventor.