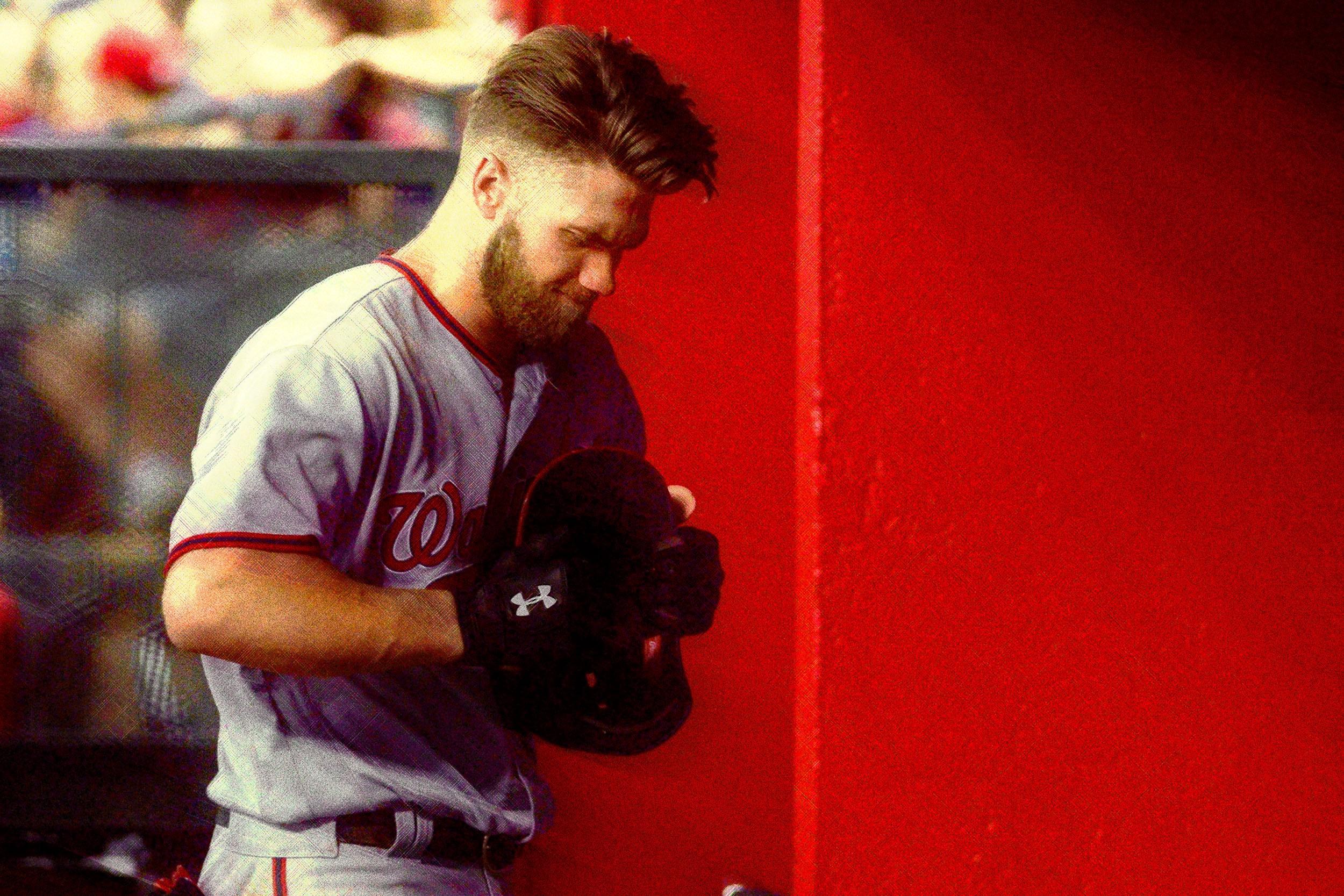

Bryce Harper is fine. He’s hitting .242/.386/.454, and I guess you can be a below-average player with a .386 OBP, but you have to be, I dunno, Adam Dunn in concrete clogs or something. According to Baseball-Reference, the only active player who’s qualified for a batting title with an OBP of .380 or higher and still managed to post a negative wins above average is Chris Coghlan in 2009. And even that’s suspect because he was supposedly 19 runs below average that year, playing primarily in left field, which is an unfathomably bad (and probably flukey) number unless, again, you’re Adam Dunn in concrete clogs.

Except, Harper is supposed to be better than just fine. He’s not only one of the most hyped prospects ever, but last year he posted a 198 OPS+ as a 22-year-old, which is basically Ted Williams’ 1941 season adjusted for park and era. So on one level, treating an “above-average” season like a crisis makes sense.

The problem is that it’s tough to tell whether this is only a crisis because Harper’s 2015 was so good for a player of his age that such a drop-off is almost literally unprecedented. Depending on the cause of his slump, you can come close to a comp with two different players. One is encouraging. The other should scare us all shitless.

The last player aged 24 or younger to put up a 190 OPS+ or better was Mickey Mantle in 1956, and he’s the only other example since World War II. If you lower the threshold to an OPS+ of 150 and increase the age limit to 25, you get 14 seasons in the past 10 years. Four of those seasons belong to Mike Trout, who may or may not be human. Take him out and you get this list: Harper, The Mighty Giancarlo Stanton, Anthony Rizzo, Paul Goldschmidt, Buster Posey, Andrew McCutchen, Joey Votto, and Prince Fielder twice.

The only two who experienced anything like Harper’s drop-off over the past year are Posey and Fielder. At age 25, Posey won the NL MVP with a 171 OPS+ as a catcher, before dropping down to a 134 in 2013. Not only was Posey’s dip in performance far less extreme than Harper’s, catchers aren’t supposed to go for a 171 OPS+. If Posey had continued to perform at that level, we’d probably have burned him as a witch by now.

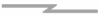

Fielder, on the other hand, went through a yo-yo-like phase not just once but twice, and his struggles mirrored Harper’s.

Though Fielder and Harper might not look that much alike, they do have a fair amount in common as hitters: Both are left-handed power guys with extremely quick bats who walk a lot and strike out less than 20 percent of the time. And like Harper from 2015 to 2016, Fielder had fairly stable plate discipline numbers from 2007 to 2011 — not completely consistent year to year, but nothing career-altering.

What killed Fielder in those off years was a decrease in isolated power — slugging percentage minus batting average, or in other words, the number of extra bases a player hits for per at-bat. One thing that can affect isolated power is the percentage of fly balls that turn into home runs, as opposed to, say, doubles or even outs. Fielder’s loss in home run rate was not as big as Harper’s, but Fielder’s overall numbers never reached Harper’s peaks or valleys because his peripheral numbers didn’t swing as much.

Almost half of Harper’s lost 195 points in slugging percentage comes from an 88-point drop in batting average, which comes from largely from a 121-point drop in his BABIP. Not only is Harper’s HR/FB rate down by more than a third, his line drive rate is down from 22.2 percent to 15.5 percent, and his hard-hit rate dropped from 40.9 percent to 32.8 percent. These numbers aren’t as precise as the decimal point might suggest — batted balls are classified by human coders, and even if they weren’t, the line between a line drive and a fly ball can be blurry — but that’s a huge drop-off. Sometimes a spike or a valley in BABIP is the result of luck — and maybe Harper’s been unlucky to a certain extent — but combined with the drop-off in hard contact, Harper’s extended slump probably isn’t random.

Except, Harper’s faced more or less the same pitch mix in 2016 as 2015. He’s swinging less than ever at pitches in the zone, but he’s making more contact than ever. Combined with his outstanding walk rate and strikeout rate, I don’t think this is an approach issue.

Last week, Sports Illustrated’s Tom Verducci reported that Harper’s been playing through a shoulder injury for the past two months, and while the Nationals deny it, that’s exactly the kind of thing that would sap Harper’s power (he’s slugging only .386 since May 1) as long as it has. We don’t know anything for sure, and Verducci’s report would suggest that Harper cooled off for almost a month before the injury, so the timeline doesn’t match up perfectly, but I can buy one cold month followed by three injured ones from Harper way more easily than I could buy four cold months in a row.

So, if we’re looking for young outfielders who followed up all-time great seasons for their age with all-time stinkers, we’ve got probably the best example in recent history of how a shoulder injury can dog a position player for years: Jason Heyward hit .277/.393/.456 as a 20-year-old rookie, one of the best seasons ever for a player his age. Then in 2011, he fucked up his rotator cuff before the season started and never got over it. He played through it until May, went on the DL for three weeks, and then came back for the rest of the year. Heyward’s numbers plummeted to .227/.319/.389 his second year, and he’s never been the same.

If this is about a shoulder injury, the Heyward precedent is much scarier in the long term than it is now. Harper’s struggles this year are disappointing only because of the lofty expectations that he comes in with — you’ll take a guy with a .386 OBP who makes $5 million, as Harper does, no matter what. Plus, when Harper needs to, he can still reach back for that power.

Moreover, the Nats are running away with the division, which gives them the option to sit Harper a little more in September if they think it’ll help. His production for the rest of 2016 isn’t the problem.

The key is to avoid what happened to Heyward, and what happens fairly frequently to players who try to play through a nagging injury: Harper might start favoring his injured shoulder in such a way that forces him to change his swing mechanics and alters the muscle memory that’s been honed over 23 years into one of the sweetest swings in baseball. Plus, it could also lead to another injury.

Whether Harper is injured — and if so, how badly — could be the difference between Fielder’s outcome and Heyward’s. Until much later in his career, Fielder always bounced back. Heyward never did.