Let me tell you a story. It’s about a student I had a couple of years ago, back before I was a full-time writer, when I taught science at a low-income middle school in South Houston, a subsection of the city that is predominantly Hispanic (I taught from 2006–2015; I became a full-time writer in 2015). I was thinking about the kid recently — about a bunch of my kids, really — because there was news about Jaime Escalante, the teacher made famous by the 1988 movie Stand and Deliver, who was honored by the USPS with a commemorative stamp.

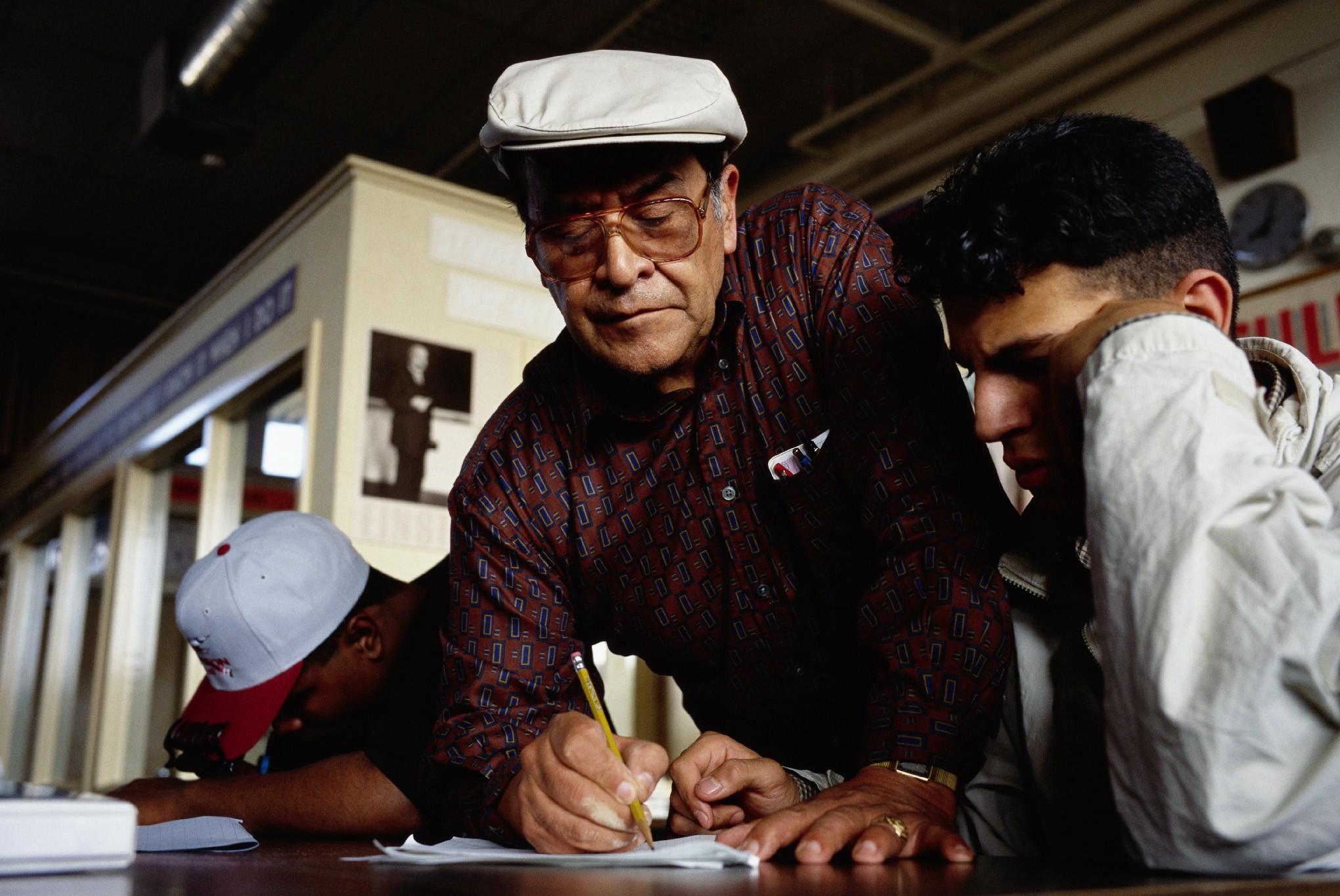

I’d watched Stand and Deliver before I was a teacher and I thought it was a good enough movie. But I was really drawn in by Escalante after I became a teacher. He was exactly the sort of teacher that I always wanted to be. I’m sure a part of that pull was a natural gravity — he looked just like one of my uncles (Escalante was actually Bolivian, not Mexican, but it was close enough for me) and sounded like nearly every old man in the neighborhood where I grew up. It’s a powerful thing to see somebody that could be you working professionally in a position that you admire. But more than that, he wanted to be in that particular classroom (desolate and nearly hopeless) with those particular kids (impoverished and largely Latino).

In college, I had a professor named Dr. Strauss. She taught a psychology class I needed for my degree. There weren’t many people in there — maybe 15, 16 of us, tops — so I don’t know if she made it a point to spend time with each of us individually. But after two or three weeks, she asked me to stop by her office. I was surprised by her request because I’d never had a professor ask to speak outside of class. Initially, I thought I was in trouble. And in a way, I was.

On the day of our meeting, I walked over to her building and then to her floor and then to her office and then to the chair in front of her desk. I said “hello” and she said “hello” and I sat down and we started talking. And it quickly became obvious that I was only there because she wanted to talk with me about being Mexican. She asked a lot of questions about my parents and my family. She asked about how I was raised. She asked if I’d ever heard of LULAC (nope) and if I’d received any scholarships (super nope). Then she asked what sort of job I wanted when I graduated and that’s the part of the conversation that has always stuck with me, and likely always will.

I told her I wanted to be a teacher, and she said that was good. Then she asked if I’d gotten to a point yet where I was starting to feel an obligation to anyone besides myself. I didn’t really understand the question, so I said something like, “I don’t really understand the question.” So she said, and I’m paraphrasing here because this was a conversation that happened 15 years ago, but she said, “OK, let me ask you a different way. You said you grew up on the South Side of San Antonio, right?”

Correct.

“And it was a predominantly Hispanic community, right?”

Very much so.

“And you were there your whole life, right? Surrounded by Latinos? Went to elementary there? Middle school there? High school there?”

Yes, yes, yes, yes, and yes.

“OK. In your 13 years of being in school, kindergarten through 12th grade, how many teachers did you have that were male and also Hispanic?”

I could only come up with one. His name was Mr. Hernandez and I had him for a music class in middle school for a semester. Other than that, there was nobody else. Not in math, not in science, not in reading, nothing. Of all of the teachers I’d ever had, and living in area like the one I was living in, only one was a Hispanic male. She asked if I thought that was strange. I told her I’d never thought about it before. She asked why not. I said, “I don’t know. I just didn’t.” She said, “Well, you’re going to be a teacher. So think about it.” Then she asked me to leave.

Teaching was a far more intense job than I’d anticipated. You have to learn the curriculum. You have to learn how to test the curriculum. You have to learn how to manage children who think they’re grown-ups (and how to manage grown-ups that behave like children). You have to learn how to weave differentiated instruction into the lessons you’re building and also you have to learn what “differentiated instruction” means. You have to learn how to manage the tiny amount of time you get with each class each day. You have to learn when and how to discipline your students and you have to learn when and how to let them just exist as children, because they are children. You have to learn all of that. Every single piece. It’s all important. But you only ever really have to be good at one thing: Making sure your students know that you absolutely, no question, no doubt, for sure, 100 percent want to be in that particular classroom with those particular kids. If you do that, shit usually works out.

Anyway, the story I promised:

In 2011, I had a Vietnamese student named Quoc. He was a gem. He spoke very little English (I taught the ESL population), but he was so charming and outgoing that it rarely seemed to matter. I remember at the start of one class, as a quick warm-up exercise, I asked the kids to draw an example of an interaction in an ecosystem. We’d spent the previous day talking about mutualism and commensalism and parasitism, and during the lesson I had a slideshow with video clips of pairs of animals interacting. The warm-up was meant to be a refresher before we moved onto the next thing.

I gave everyone five minutes to finish. After about three or so minutes, I started wandering around the room, peeking over shoulders to needle kids about how poorly drawn their lions were. When I got near Quoc’s table, he immediately folded up the page that he was working on and stuffed it in his pocket.

I said, “Quoc, what’s up? What ya’ got there?”

He just looked at me and smiled, but he didn’t say anything.

I said, “Quoc, what’d you draw? Let me see.”

He squeaked, “No.”

I said, “Boy, if you don’t give me that paper, I’ma wop you in the head with this meter stick.” (I was holding a meter stick.) (I wasn’t actually going to wop him.) (I think I led the league in threatening to wop kids in the head with a meter stick for the duration of my teaching career.) (I was last place in AWD [Actual Wops Delivered].)

Quoc reached in his pocket, took out the paper, handed it to me, then put his head down on the table in embarrassment. I began to open the paper, and as I was doing so I could feel the other kids in the classroom looking at me because middle-school kids have heavy, clumsy stares. I got the page all the way unfolded. I must have made a face because one of the girls sitting nearby asked, “What is it?”

Do you know what it was? I’ll tell you what it was. I’ll tell you exactly what he drew on that piece of paper when I asked everyone in the class to draw an example of interaction in an ecosystem because I will never ever forget it for the rest of my life. He drew a picture of a duck. It was standing next to a turtle. The duck was telling the turtle, “Fuck you,” except he spelled it “Fack you.”

I was so goddamn happy when I saw it. I didn’t even try not to laugh. Matter of fact, I laughed very loudly. The girl asked again, “What is it?” I said, “Quoc drew a picture of a duck cussing out a turtle.” She said, “Oh.”

I don’t know if he drew it hoping it was the correct answer or if he was just looking for a reason to use to the word fuck (or fack). Either way, it was great. I think I lived on that moment as a teacher for a good three, maybe four weeks.

There are big, obvious, expected moments built into the school year that help you stay engaged and focused. Like when it’s time for the state-mandated tests that get used to determine if a kid gets promoted (and how effective you are as a teacher) or the year-end graduation ceremonies. Those are always there, and you know when they’ll arrive. But just because you know they’re coming doesn’t make them any less meaningful — getting to tell a student I care that he or she passed the STAAR test and would be promoted to the next grade was always an emotional, rewarding moment. It was as good as it was pulverizing when I had to tell someone he or she was a couple of questions short and didn’t make it and failed for the year.

But those small, unpredictable, unexpected moments that happen are the ones that stay with you the longest.

The last scene of Stand and Deliver is a long shot of Jaime Escalante, played by Edward James Olmos, walking down the hallway of his school toward the exit doors. It happens after the principal of the school shares a phone call with someone who tells him that Escalante’s students, a group of poor Mexican kids who’d been accused of cheating because they all scored so well on a statewide AP calculus exam, had been cleared of any wrongdoing. As he walks down the hallway, text appears on the screen. It reads, “In 1982, Garfield H.S. had 18 students pass the A.P. Calculus Exam,” and every few seconds the number for the year increases and the number for the amount of students that passed the exam increases (1983, 31; 1984, 63; 1985, 77; etc.).

As Escalante reaches the door, he does a quick but easy-to-see single fist pump. He isn’t celebrating for himself. He’s celebrating for his students.

I always wondered what smaller moments Escalante kept with him, that he celebrated, that he told to friends over drinks or shared with his family at the dinner table. Who was his Quoc? Every teacher has them. I’m guessing every person in every profession does. But I know every teacher has them. I wonder what his were.