In the spring of 1957, when Donald Trump’s grade level matched that of his present-day speech, Warner Bros. released A Face in the Crowd, extending Elia Kazan’s directorial streak to nine consecutive years with a major motion picture. This one wasn’t as major as Warners wanted. The preteen Trump probably didn’t take a break from bullying his Queens classmates to see it; by Kazan’s own admission, “only a few people” did. Marketing-wise, the movie had terrible timing: Its story, which chronicled a charismatic megalomaniac’s rise from media personality to political power (ahem), arrived right after a well-liked Ike had swept away Adlai Stevenson in a lopsided presidential election, following a first term in which he’d averaged a 70 percent approval rating. With the country united behind a mild-mannered granddad who’d helped win World War II, Kazan’s dark warning was a drag, daddy-o — and maybe too much to believe.

We’ve come quite a way since those not-so-idyllic days of segregation, discrimination, and Cold War. But the mood of modern Americans is down by default, which makes A Face in the Crowd — now pushing 60 — a better fit for the current climate than it was for ’57. Kazan and screenwriter Budd Schulberg (who had previously combined forces for On the Waterfront and, less gloriously, naming names to the House Un-American Activities Committee) tried to predict how the mass media’s power to touch many more people would alter the way we make stars and select leaders. They came close to the mark, but in the wake of this week’s Republican National Convention, they’ll have to settle for a special distinction: being both the first to anticipate and the first to underestimate the influence of a figure like Trump.

A Face in the Crowd is the better-bred ancestor of today’s scare films about cell phones and video chat, a cautionary tale about another new-at-one-time technology: television. When TV invaded, our defenses fell: In 1950, fewer than 10 percent of American households had a way to watch Jack Benny, but by 1957, more than three-quarters did. Given how quickly TV took over, it was easy to wonder whether the new piece of furniture held some sinister power. Maybe the idiot box wasn’t only a Dragnet delivery system, but also — as one of A Face in the Crowd’s paternalistic power brokers puts it — “the greatest instrument for mass persuasion in the history of the world.”

The film’s titular face belongs to Larry Rhodes (Andy Griffith, in his first film), a drifter from “all over” and the son of a “spieler with a two-bit con.” He’s headed for the same fate as his father until he’s discovered in a drunk tank by Marcia (Patricia Neal), a country radio producer who’s looking for local color. She nicknames him “Lonesome” and gives him a morning show, a folksy First Take for the Arkansas crowd. “Watch him, he’s a mean one,” a cellmate says, and soon, the world does.

Lonesome’s got a gift. “How does it feel?” Marcia asks him. “Saying whatever comes in your head and being able to sway people?” His smile tells us it’s intoxicating. The microphone makes him more powerful, but as a small-town talker before satellite syndication (and during the days of the Fairness Doctrine), his mischief is mostly harmless. TV breaks the quarantine, providing him with a platform big enough to do damage. He leaves town like a conquering candidate on a whistle-stop tour, plunging into shadow as he looks toward larger crowds.

As his ratings bring him riches, Lonesome whitewashes his origins and hides his contempt for his fans. On camera, he comes off as more honest than anyone — “a truthteller in a hypocritical civilization,” as Kazan called him, willing to stray from his scripts and appeal to viewers who rarely see themselves on the screen. For the fiction to work, we have to believe that this character could captivate a country. Griffith, still a few years away from moving to Mayberry, is mostly up to the task: As raw a performer as Rhodes, he plays Lonesome large and loud, IRL drunk in some scenes that required an especially savage performance. Like us — and like the recognizable reporters who lend life to Lonesome the way their successors do for Frank Underwood — Marcia can’t stop staring, her face flitting between fear and fascination.

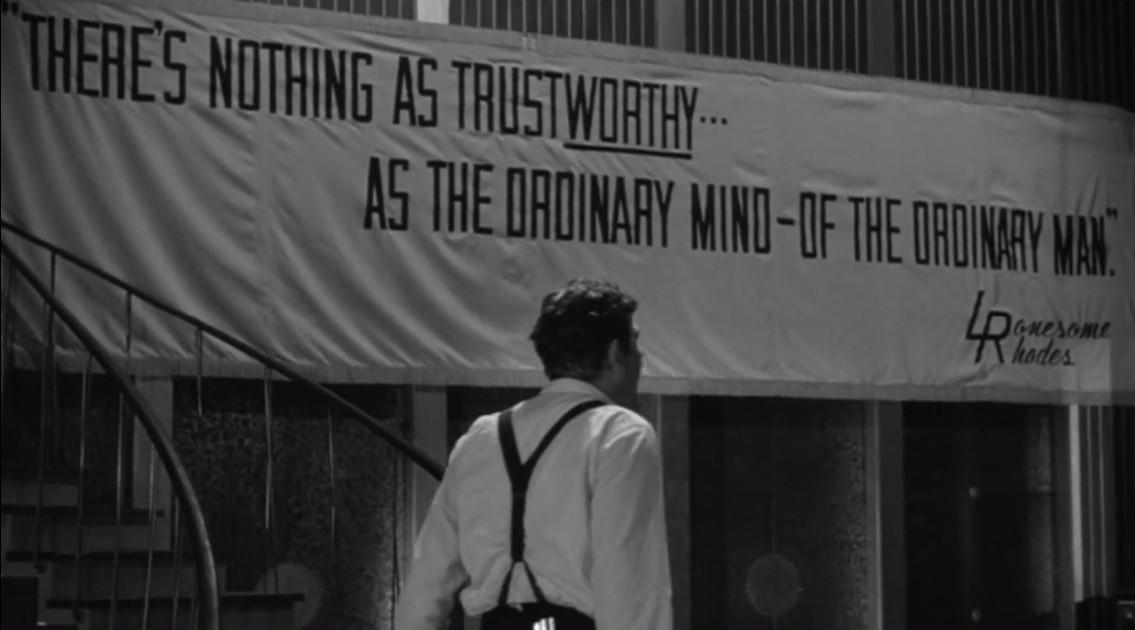

Lonesome can push any product, but no one can control him: Hold open the back door, and he’ll slide through the front. A peddler of bullshit, he’s his own biggest buyer. Convinced the nation needs him, he sheds his country trappings, trading straw hats for suits and posing for portraits in magazines. On air, he ditches his guitar and opines on politics; off air, he becomes a consultant to a soporific senator’s presidential campaign, helping him craft a “new personality” that’s flashy enough for TV. When Lonesome’s coaching pays off — despite some distinctly un-Donald advice not to hide his hairline — he’s fitted for a newly created Cabinet position, ominously named “Secretary for National Morale.”

For a black-and-white box office flop and an AFI omission, A Face in the Crowd has been coming up often (just as it did during Watergate). The Trump parallels are plain: Like Trump, Rhodes breaks from convention (Rhodes mocks his sponsors; Trump eschews ads), gets accused of fascistic tendencies (in Rhodes’s case, by Kazan), lives in the penthouse of a Manhattan tower, and parlays his TV popularity into real power by playing to the people who have to “jump when somebody else blows the whistle.” A broader reach has enabled Trump’s Rhodes-like rise to prominence, just as Schulberg and Kazan foresaw. And the longer Trump defies his unfavorables, the more his detractors look like Marcia in her “after” photo.

There’s a long line of American movies — from The Best Man and The Candidate to Wag the Dog and Bulworth — that reflect our disillusionment with politicking’s tendency to select vapid and venal leaders, people who survive because they can spin their way out of a sex scandal and who attain a certain prominence because they have nothing of interest to say. A Face in the Crowd, which Kazan described somewhat boldly as “the first film that shows the power of the means of communication,” isn’t so world-weary. It presents a very real risk, not just that we’ll wind up with ineffectual leaders, but that we’ll wake up too late to someone so dangerous that (as a non-fictional politician once said) “this sucker could go down.” That urgency makes it resonate now.

For all his apprehension, though, Kazan doesn’t despair. The future he sees has dystopic traits, but it’s also self-correcting. “On the one hand, [TV] can be very beguiling and can turn a man into a hell of a salesman,” he said in 1970. “On the other hand, if you get very close and expose a man enough, sooner or later he’s going to reveal who he really is.” Cameras and mics give people power, but they also up their odds of making a costly mistake.

At the height of his celebrity, Rhodes is sentenced to death by live mic, betrayed by Marcia, who hijacks the control room to take down the monster she’s made. “Pull the mask off him,” says Marcia’s writer friend Mel (Walter Matthau). “Let the public see what a fraud he really is.” Not knowing the country can hear him, Lonesome smiles and waves while scorning the “miserable slobs” who drive his ratings, announcing, “I’m gonna start shootin’ people instead of ducks.”

The public’s vengeance is improbably (if satisfyingly) swift: Kazan shows us shocked faces, angry crowds, and switchboards burning up. By the time Lonesome completes his descent from the studio, he’s been pulled from the air, and his famous friends have disowned him. He’s reached the ground floor in every respect.

In the current race between disliked and distrusted candidates (and candidates’ spouses), each side’s supporters started out daydreaming about the other’s explosive demise; Hillary haters still hope the next congressional hearing or FBI investigation will pierce her practiced façade, exposing the deceiver they believe lurks beneath. But Trump’s resilience makes that urge to unmask seem almost old-fashioned. He might be wearing a weave, but concealed scalp aside, his flaws are all out in the open. They just haven’t doomed his campaign.

When Trump isn’t talking, he’s tweeting, and his statements go far beyond “gaffe,” treading on oh-my-god grounds that could kill other campaigns. Kazan was right to imagine a world where sins are hard to hide: When scrubbed posts can be cached, deleted tweets can be saved via screenshot, and smartphones see all, a VIP’s undoing is always one upload away. If something Trump said dragged him down, he wouldn’t be the first billionaire named Donald to be sunk by his own loose lips. But so far he’s unsinkable, even when (like Lonesome) he talks about shooting people. And he doesn’t apologize for the insults he utters, even as he goads others into apologizing for the insults they hurl at him.

Now he’s a nominee. And sure, the forecasts still say he probably won’t win. But for those who oppose him, a mere election-night loss after so long in the limelight would be less than a real repudiation, a reminder that he once was a Hillary misstep away.

Kazan said his film was ahead of its time, and in some ways it was. But the still-vital work is also a bit behind ours. Look at the latest polls, or the appointment of Trump’s oddly coiffed counterpart across the Atlantic, and Lonesome’s slogan starts to look like a lie.

“You were taken in, just like we were all taken in,” Mel says to Marcia in A Face in the Crowd’s closing seconds. “But we get wise to him. That’s our strength. We get wise to him.”

It’s a nice sentiment that sounds pat today. Lonesome Rhodes was unnerving enough, but this year’s too-real remake asks a more disquieting question: What do you do when the mask is removed, and people still like what they see?