Samaria Rice was lying in bed one morning this month when she began to wonder if she should watch a man die.

She did not want to. For nearly two years, Samaria had done all she could to avoid consuming the news. Stories of shootings brought on panic attacks. Even the sight of police officers could make her pulse quicken. Not long ago she’d been a mother of four with dreams of a career in real estate; now she was a mother of three with dreams of a federal indictment. She spent nearly every day reliving the worst moment of her life, and sometimes her only solution was to close all of her blinds and turn off all of her lights and shut her eyes, hoping that when she awoke she’d find the world just a little easier to bear.

But now she couldn’t sleep. Friends were texting to ask if she’d seen what happened to a Baton Rouge man named Alton Sterling. Her Facebook feed was flooded with links to a video showing the moment when officers shot Sterling multiple times while he was pinned to the ground.

Scrolling through her phone, Samaria paused, her thumb hovering over the screen. She knew vaguely what the video would show, and she knew acutely what emotions would arise. "I really wanted to avoid it," she says, sitting in a Cleveland hotel lobby a week later. "But I felt like it was my duty, you know? I felt like I had to watch it. Because of, well …

"You know."

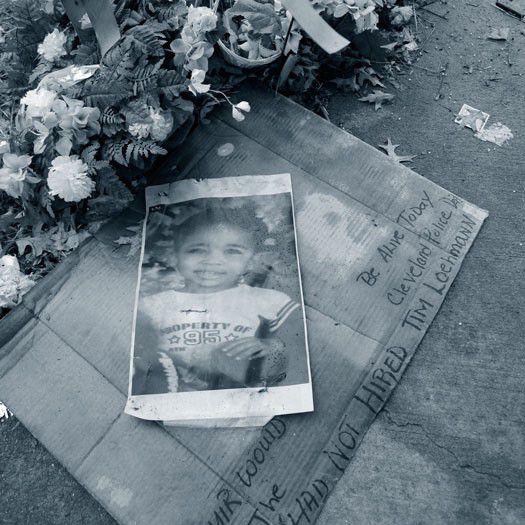

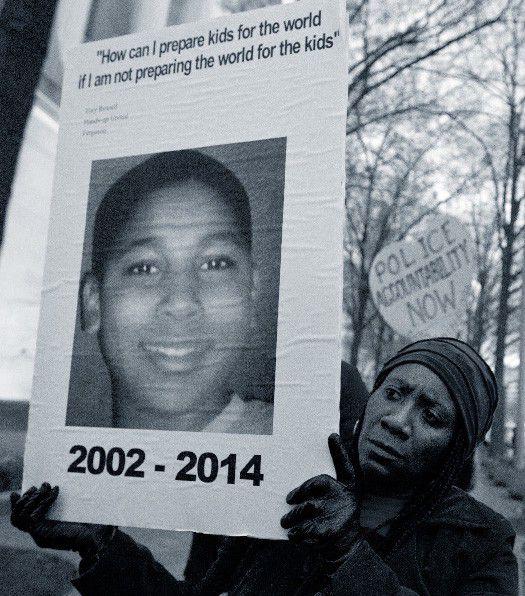

On November 22, 2014, Cleveland police fatally shot 12-year-old Tamir Rice. Twenty months later, his mother is still desperate for the time and space to grieve.

The cycle has become familiar. Ferguson, Cleveland, Baton Rouge, Falcon Heights. Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, Alton Sterling, Philando Castile. Seemingly countless others. All with an inciting event: the death of a black civilian — sometimes a black child — at the hands of law enforcement. All with an immediate reaction: scrutiny from reporters, anger from protesters and venom from counterprotesters, all burning hot for weeks or months before simmering down. Eventually the attention shifts, focusing anew on the next tragedy. The dead are not quite forgotten by the public, but not quite remembered, either. They become names listed in speeches by activists and politicians, in articles like this one. And their families are left, in a world that has gone quiet, trying to figure out what comes next.

"Don’t forget," says Samaria. "You see all these protests. That’s good. You see this whole movement. That’s good. You see all these different people with all these different agendas. You see celebrities making speeches. But underneath it all there’s somebody like me with a dead son."

Tamir Elijah Rice was boisterous and sweet, a boy in perpetual motion. At school, he liked to pass out papers or help teachers erase the chalkboard. At home, he liked to cook ramen noodles and watch Curious George. On the basketball court, he liked to smile as he talked trash, launching 3-pointers over other boys his age, delighting in the fact that, even in the sixth grade, he was strong enough to shoot from long range. He liked to play soccer and the drums, to swim and to dance. He was still figuring himself out. Says Samaria: "He had only been 12 for five months."

On the morning of November 22, 2014, he woke up feisty and energetic. He was already awake when his mother and siblings came to the kitchen for breakfast. His 16-year-old brother Tavon was sick, but that didn’t stop Tamir from teasing him. It was a cool Saturday, and Tamir would spend it the way he spent so many other Saturdays, playing a couple of blocks away from home at the Cudell Recreation Center.

Samaria had only recently begun letting her youngest kids, Tamir and Tajai, then 14, leave the front porch for Cudell. She wanted them close, but the rec center was close enough. If Tamir was on the park’s baseball field, she could see him from her front door. If he was on the gazebo, she only had to walk to the end of her block to catch a glimpse. If he was playing inside, she just had to make one phone call to check in. She knew the center’s staff members by name. Tamir had always clung tightly to his mother, and she tried to keep tabs on him at all times. But, she says, "I couldn’t watch him every moment of every day."

That day Tamir borrowed a pellet gun from a friend. Out there on the gazebo, he waved the gun around, pointing it and pretending to shoot. Samaria didn’t know and would have been livid if she had. "He knew not to let me see him playing with a gun," she says. "There’s no way I would have let that slide." But she was tending to Tavon, stuck on the couch with the flu. That afternoon, Samaria walked down the street to buy Theraflu at CVS. On her way home, she says, she stopped cold right on the sidewalk. "It was like an inner-body experience," she says. "My entire body went numb."

Minutes later, after arriving home, she heard a knock at the door. Two boys she didn’t recognize stood there when she opened it, shouting that her son had been shot by police. Tavon bolted from the couch and out the door to see his brother. Samaria, not quite believing, took a moment to grab her coat and follow. She arrived to find sirens and yellow tape. Her daughter Tajai was in handcuffs, having been tackled by police while running to Tamir, who was now lying prone on the ground. Samaria screamed.

She was given a choice. Stay at the scene with her daughter, or ride in the ambulance with her son. She hopped in the passenger’s seat of the ambulance, and on the way to the hospital she came undone. "Y’all better hope he lives!" she remembers screaming at whoever could hear her. "You better pray he lives! I’ll have all your badges! I’ll have y’all motherfuckers playing down in Pelican Bay!"

Pelican Bay is a state prison in California. In the darkest moment of her life, while her son lay in back of the ambulance near death, Samaria threatened the people responsible not with violence, but with prison. She showed fear and rage, yes, but for at least that moment, she also showed something else: Faith that justice would be done.

At 12:54 a.m. on November 23, Tamir Rice was pronounced dead.

Details emerged as days passed. A man had seen Tamir with the pellet gun and called 911. "A guy," he said, was pointing a gun. He was "probably a juvenile," he said, and the gun was "probably fake." The police radio worker who took the call neglected to tell the dispatcher that the caller had said the gun was likely fake. The rec center’s surveillance video showed that minutes later, officers Frank Garmback and Timothy Loehmann pulled into the facility and up onto the curb. Within two seconds of exiting the car, Loehmann shot Tamir in the abdomen.

News of Tamir’s death went national, and so began the cycle that has now become routine, our public reckoning with another death of another black civilian at the hands of police. First: horror. This time, it was a 12-year-old child. This time, it was on video, released by police four days after the shooting. Next: an attempt to rationalize. The toy gun was missing the orange plastic that marked it as fake; officers thought Tamir looked much older than 12. Soon came the protests and the long-running investigation, and then, last December, the announcement that no one would be indicted in Tamir’s death.

His family settled a lawsuit against the city of Cleveland in April, for $6 million. "A settlement isn’t justice," Samaria says. The family has requested a federal investigation, currently under review by the U.S. Department of Justice. For now, Samaria waits.

Even before November 22, 2014, Samaria had lived a life filled with pain. Samaria says that she bounced in and out of foster care between ages 12 and 18, after her mother was sentenced to 15 years for killing an abusive boyfriend. Once she reached adulthood, Samaria endured her own abuse. She gave birth to Tamir while living in a shelter. In 2013, she was sentenced to two years of probation for trying to ship more than 3 pounds of marijuana by mail.

Samaria brings up her own convictions unprompted. "I do have a record," she says. "You can look me up in the system." Many did. Local reporters and defenders of the police began referencing her record — which also includes a 2001 guilty plea on an assault charge — soon after her son’s death. Also mentioned: The record of Tamir’s father, Leonard Warner, who was largely absent from Tamir’s life and carries multiple domestic violence convictions, including one from a 2001 attack against Samaria.

Those references were part of the pattern, of the rhetorical cycle that has now become familiar: the counternarrative that landed on Eric Garner’s multiple arrests and Laquan McDonald’s "extensive juvenile record," that picked through Trayvon Martin’s social media accounts in search of tattoos and shirtless selfies. Yet because of Tamir’s age, the focus shifted. Instead of picking through his own past, bloggers sifted through his parents’. "If cops’ addresses can be published in The New York Times and their lives put under a microscope," wrote M. Catharine Evans in American Thinker, "then the egg and sperm donors of the young Tamirs who end up getting killed are fair game."

Says Samaria: "You can talk about me all you want, but you will never taint that little boy. No. No. He is 12. He is a child. He is pure. You will not taint him, because I will not let you."

Samaria never wanted to be an activist, but staying silent is a luxury left to those who aren’t mothers of dead sons. She had watched news coverage of other deaths: Martin, Garner, Brown. She felt horrified but removed. "Honestly," she says, "I never imagined it would be one of my kids."

For weeks after Tamir’s death, she says, "My mind was in a fog." Anger and sadness had been numbed by shock. It wasn’t until January 2015 that the shock subsided and the reality of Tamir’s absence set in and she finally began to come undone. All around her were reminders of loss. Here was the kitchen where Tamir had fixed the whole family ramen noodles, so proud of his ability to cook them for just the perfect amount of time. Here was the floor where they’d played airplane, Samaria holding her son’s hands and lofting him into the sky, warning him that at 195 pounds, he was getting far too heavy for this game. There were countless other reminders. The couch where they’d cuddled and watched Clifford the Big Red Dog. The street she’d run down after hearing he’d been shot. And just a couple blocks away, the gazebo where she’d seen him on the ground, her youngest child clinging to life.

Home became unbearable, and that January, desperate to get away from constant reminders of her son’s death, Samaria and her daughter Tajai moved into a homeless shelter for about three months. "The shelter was great," Samaria says. "We needed to get away from that house, and it was a good place for us while we found a new place to live."

By this point, activists from around the country had long ago descended upon Cleveland. Op-eds had been written. News networks had come and gone and come back again. Samaria was overwhelmed. "I don’t think people fully understand what this is like for these families," says Gregg L. Greer. A Chicago-based minister and civil rights activist with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Greer worked closely with Samaria, advocating on her behalf as she dealt with lawyers and reporters, and trying to draw national attention to Tamir’s case. Greer has worked in a similar role with other families of victims of police shootings. "Not only have they lost someone, but now they’re thrust into this public position. They’re not activists. They’re just people. They don’t know how to advocate for themselves. They don’t fully grasp how the legal system works. They don’t know how to deal with the media. It’s an incredibly difficult situation in so many ways."

Activists could channel Samaria’s anger, but could never fathom her loss. Public death leaves little space for private grief. She wanted the protests to grow, but she couldn’t bear to join them. She was thankful for the nation’s outrage but desperate to be alone with her kids. Online and in the streets, Tamir’s face became a symbol of injustice. In her home, images of her son only served to remind her of what she’d lost.

"Sometimes," she says, "I feel selfish. Because I appreciate the support and the love. I really do. Because I know people want to be there for me. I know they want the same things I do. I know they want justice for Tamir and for all black and brown people being killed by police. But at the same time, you see some things, you see people selling T-shirts with his face on them, or you see people dropping his name for their cause, and I just want to go: ‘I don’t remember you being there in the delivery room. I don’t remember you being in our house with us. I don’t remember seeing you ever before in my life.’"

Much of the time, though, Samaria is grateful for the broader movement that surrounds her cause. As time has passed, she has forged relationships with the mothers of Garner, Martin, Brown, and others killed in high-profile cases with civil rights resonance. "My moms," she calls them. "Sometimes it feels like they’re the only ones who understand."

As time has passed, she has come to embrace her role in the larger movement around police reform and the value of black lives. "I realized this is what I’m supposed to be doing," she says. "Sometimes it hurts. It’s exhausting. It’s overwhelming. I was never really about supporting my people before. I was about just trying to raise my kids. But now I see that we need to speak out. Somebody has to tell the government to stop murdering black and brown people. If I have to do it, I’ll do it."

So long a target of national mockery and a symbol of Rust Belt decline, Cleveland has seen a renaissance in recent years. Downtown has been revitalized. The economy has taken an upward turn. LeBron is back and the Cavs are champions. But as pieces of the city grow, others risk being left behind. Wide swaths of the city’s East Side have been neglected and economically depressed, and even on the more diverse West Side, where Tamir lived, some neighborhoods remain in the grips of poverty. "I think you do see a ‘renaissance,’ but it’s much more complicated than that," says Cleveland City Council Member Jeff Johnson, who was among the more vocal elected officials to advocate on behalf of Tamir. "When you have 40 percent of your population at x3 or below the poverty line, two-thirds of the students in your city’s schools at or below the poverty line, what you have is a large segment of this city who is still hoping to become a part of this renaissance."

While Tamir’s death resonated nationally on a level few other deaths have, his case never gained the same local momentum as Brown’s in Ferguson or Garner’s in New York. "Cleveland," Samaria says, "was asleep. They still asleep."

"You would go to the protests," says Cleveland Scene reporter Sam Allard, "and you’d usually see a few dozen people marching. That was really it." In part, this may have been simple fatigue. By the time of Tamir’s killing, Cleveland residents had spent years protesting another killing by police. In 2012, an officer tried to pull over Timothy Russell, a Cleveland man who failed to signal for a turn while driving a 1979 Chevy Malibu in an area known for drugs. When Russell sped away, alongside passenger Malissa Williams, officers pursued them for 22 miles. Officers heard a loud noise — which investigators later said was likely the Malibu backfiring — and when the chase ended in a middle school parking lot, they fired 137 shots into the car. One officer, Michael Brelo, fired more than 40 shots himself, including at least 15 after jumping onto the hood of the car. Both Russell and Williams were killed. Both were unarmed.

Brelo was indicted on two counts of voluntary manslaughter but was acquitted last May. "You know," says Johnson, the city councilman, "there was actually a lot of hope that Brelo would be convicted. When he was acquitted, I think that took a lot of energy out of the community."

By the time it was announced, last December, that there would be no indictments in connection with Tamir’s death, modest police reform was already underway. After the killings of Williams and Russell, Cleveland Mayor Frank Jackson requested a federal investigation into the police department’s practices. The Department of Justice found a pattern of "unreasonable and unnecessary use of force" in the CPD and issued a consent decree last May that led to reform efforts. Among the changes: Pistol whipping and warning shots were banned, and officers could no longer use force as punishment for talking back or running away. The department would also be watched closely by an independent monitor, a system that remains in place.

Says Johnson: "This process was already in motion when Tamir was killed. So, while Tamir’s death resonated powerfully on a national level, locally, this was one in a long line of many cases that fit into this pattern that needed reform."

As a toddler, Tamir suffered from separation anxiety. "That was one clingy baby," Samaria says. When she would go to the restroom, he would scream for her to return. Each night when she made dinner, she perched him nearby, so he could look on as she cooked his meals. When he started going to preschool, Samaria sent a picture of herself with him. Look, teachers would tell him. Here’s your mommy. She’ll be back to pick you up soon.

As he grew, Tamir became more independent, but Samaria always kept him close. In the weeks before his death, Tamir returned to a younger version of himself. "He was hugging me all the time," Samaria says. "He was kissing on me all the time. For a few weeks, he was just real clingy again." Moments later, she continues: "I didn’t know why. Now I see why. It’s like he was preparing me or something. He was just being so sweet.

"And then they took him."

Around 11 p.m. on the night he was shot, Samaria was allowed into Tamir’s hospital room. Her son was unconscious. Tubes protruded from his body. She was unsure what was keeping him alive. She tries not to think often of those final moments in that room, when she tried to comfort him. She wanted to hold the boy who had once been so desperate to be near her, who had felt anxious each time she left his sight. She held his hand, but she wanted to hold his body, to provide whatever comfort she possibly could. But when Samaria reached for him, she says, an officer told her not to. "His body," she remembers the officer saying, "is evidence."

Telling the story, Samaria shakes her head. "Evidence," she says. "Evidence. I never got to hold him. I never kissed him goodbye. Evidence."

Sometimes, she drives through west Cleveland, past row after row of old houses and empty lots, past her old home, down Detroit Avenue and up West Boulevard, and she pulls into the parking lot at Cudell Recreation Center. This, she tells herself, is the last place she really saw her son. The memories of the hospital are too painful. Here in the park, though, she sometimes finds peace. There is a butterfly garden, arranged in his honor, and there are wooden posts painted with his name. "We gon’ be alright," says one, in an apparent reference to the Kendrick Lamar song and Black Lives Matter anthem "Alright." "Young black king Tamir," says another. In the field and on the playground, small black children run and shout and play.

"I feel his spirit in those kids," says Samaria. "I feel like he’s a part of them, like he’s still just being a regular kid."

Last Wednesday, there on the gazebo, a group of children walked up to the pile of stuffed animals left in Tamir’s memory. Some of the animals have been there for months now — large and small, ripped and intact, dirty and clean. A girl named Delilah, age 8, picked up the animals and held them before her 4-year-old cousin, Marquise.

"What’s this one?" she asked.

"A frog!" he shouted.

"What’s this one?"

"A cat! Meow, meow!"

When asked if she knew why the animals were there, Delilah nodded. "I used to live right around here when it happened," she said. Then she turned to Marquise and asked him: "Do you know why the animals are here?"

He was standing footsteps away from the patch of grass where the squad car jumped the curb in 2014. There was the spot where Tamir Rice was playing, right up until the moment Officer Loehmann exited his car and drew his gun.

Delilah asked Marquise again: "Do you know why the animals are here?" Marquise, however, was oblivious, unlistening, delighted to be spending a moment with new toys. An elderly companion watched carefully from a nearby table, ready to intervene should any trouble arise, so Marquise was free to play as he wished. He was holding a stuffed turtle but making it bounce like a frog, and then he was grabbing a Rastafarian monkey and laughing at its dreads, and then picking up a teddy bear that was missing a leg and squealing mischievously as he inspected the stuffing inside.

Delilah didn’t ask again. "He’s not listening," she said. For a while longer, she just watched as her little cousin played.