Consider the immediate context. Alton Sterling. Philando Castile. The waves of protests nationwide, ever-widening in their arcs. The Dallas police shootings. The ritual stages of grief, disbelief, madness. Consider the moment: the summer of an election year, one so dire and so crucial it’s been drawing comparisons to 1968. It’s as much a culmination of an untreated ulcer, ours and everyone else’s, as that summer. But a key difference between then and now is that our flare-up isn’t over. It’s not history yet: We don’t know how bad it’s going to be.

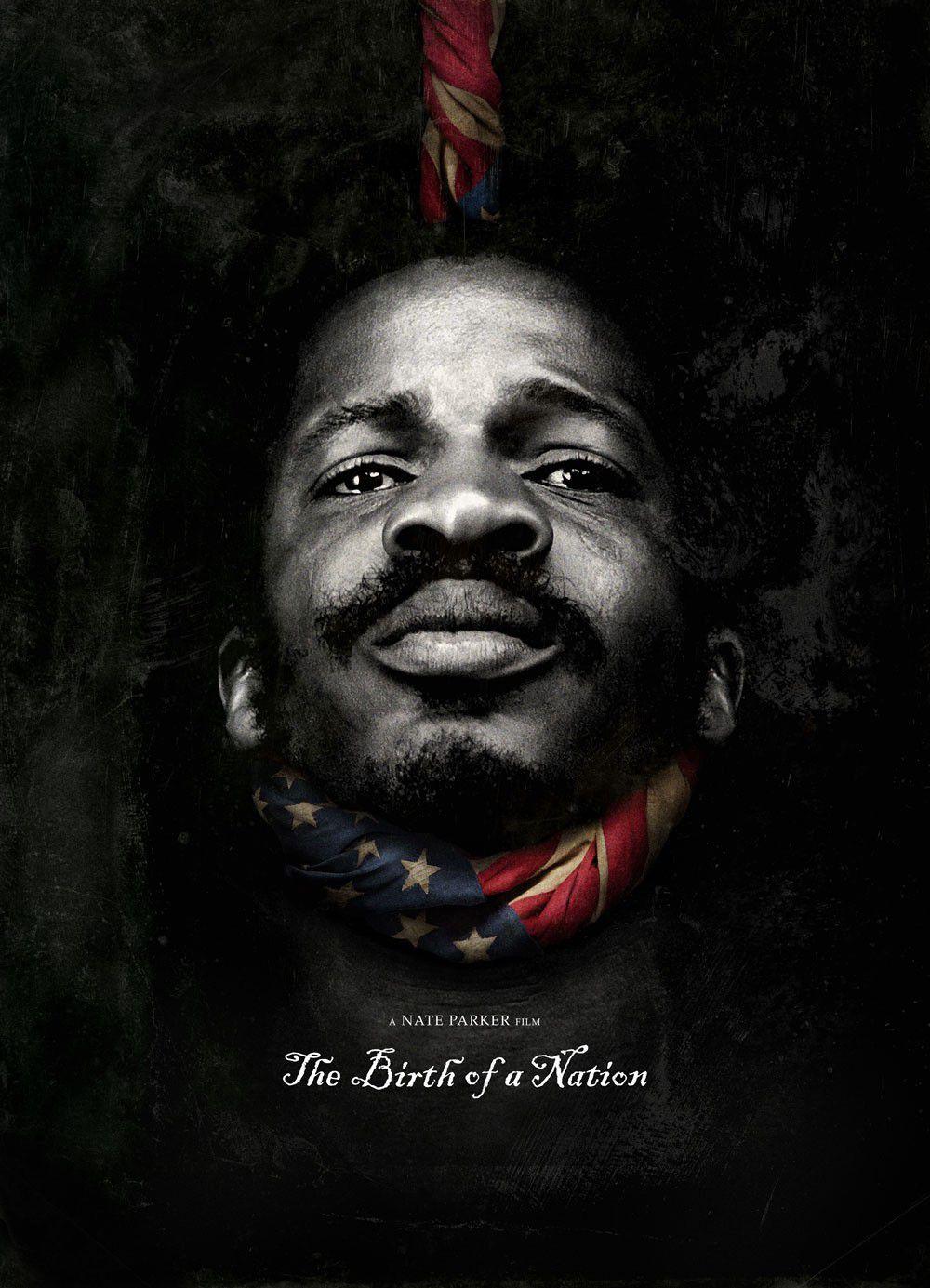

Consider, then, the astonishing certainty of this image: a silent black face beckoning from out of charcoal darkness, teary, strung up by the neck. The face is sculpted in black and white. But the noose is all color: stars and bars in a familiar red, white, and blue.

That image, which dropped on Tidal this weekend, is the new poster for Nate Parker’s upcoming fall movie, The Birth of a Nation, which has been causing a stir among critics and eager audiences since its debut at Sundance earlier this year. News of its reception read like a religious revival, and the movie was described like a downpour after an unknown drought, something the industry didn’t know it needed but suddenly couldn’t get enough of. It received “one of the longest standing Os in recent festival memory,” won the top two prizes and nabbed an unprecedented $17.5 million deal from Fox Searchlight.

It was hailed as “a film very much in tune with the current state of heightened racial friction,” too, though the movie’s immediate concern is not with the present but rather the slave rebellion led by Nat Turner in August of 1831. It seems, though, that writer, director, producer, and star Nate Parker has consciously planned for his movie to reach outward toward its many contexts — including Hollywood — since its conception. The movie’s title tells you as much. D.W. Griffith’s 1915 The Birth of a Nation was, after all, our nation’s first blockbuster. It has long been a stain on Hollywood that the modern American film industry — from its function to its establishment as a method of making movies — was born of a movie that sparked a surge in racial violence and reignited the KKK. We can’t imagine Hollywood — or 20th-century America — without it lurking in the shadow of that industry. Particularly right now.

Suffice it to say our current conversations about race and Hollywood are, uh, loaded. And the Academy Awards have become the center of those debates, perhaps because, as an annual, predictable, immovable event, they aren’t a moving target. They don’t change. But their particulars vary from season to season, and this year, an early front-runner for the top awards is a slave rebellion movie titled The Birth of a Nation. Nate Parker, you couldn’t have planned it better. The Birth of a Nation is expected — in some ways, preordained — to pick up a handsome chunk of nominations. That’s in part because its distributor, Fox Searchlight, has a strong track record — look no further than recent Best Picture winner 12 Years a Slave — and in part because of the Academy’s sudden urgency to honor more movies by, about, and starring people of color in light of multiple years of #OscarsSoWhite controversy.

We understandably tend to frame this discussion as a question of whether or not the over 6,000-member Academy, which as of this year will be a smidge less white and male thanks to an ongoing push for diversity, will recognize black movies. But the more interesting question, one spurred by the new Birth of a Nation poster, is whether this may be the rare occasion that black audiences flock to an Oscar-hungry black movie.

What if we stopped asking whether the Oscars care about black movies and started wondering whether black audiences care in any substantive way about Oscar prestige? It’s a matter of clarifying the audience for such movies. A look at the lack of overlap between the highest-grossing black movies from 2015, 2014, and 2013 — years that saw an upswing in movies on black subjects — and recent black movies nominated for Best Picture (Precious: Based on the Novel Push by Sapphire, 12 Years a Slave, and Selma) suggests that black audiences are still slow to embrace Oscar-friendly black films. The notably and, for some, surprisingly underrecognized Straight Outta Compton, meanwhile, is the highest-grossing movie by a black filmmaker. Ever.

This is a simplification, of course: some Oscar nominees, like Selma, still feel like snubs, and the merits of others are debatable. But the broader point holds: religious movies, aspirational comedies, and pulpy black thrillers like The Perfect Guy, none of which is a category of interest to the Academy, hold sway with black filmgoers — much to the still-persistent shock of numbers-runners in the industry. In fact, for five consecutive weeks in 2015, movies with black leads (Straight Outta Compton, War Room, and The Perfect Guy) topped the American box office.

Movies by and about black people have lately been good at proving the purchasing power of black audiences. But the most Oscar-friendly black movies — such as Steve McQueen’s challenging, impressive, and consensus-supported 12 Years a Slave, which did go on to awards success, and Lee Daniels’ The Butler, which (thankfully) did not — are not a part of that conversation, despite their success. The story of those movies is the story of their appeal to white audiences: 43 percent of 12 Years a Slave’s audience was white, according to The Hollywood Reporter, and The Butler’s was a majority 55 percent.

These movies could not survive without the suburbs — then again, neither (the story goes) could hip-hop — and that may in part be because they did not specifically campaign for black attention. The trailers and posters for 12 Years and The Butler seem targeted at a broadly American audience, anyone for whom the fact of a black movie about black history is not a conversation-ender. The new poster for The Birth of a Nation, on the other hand, may help the movie become successful with the Academy despite its deliberate shout-outs to black filmgoers, specifically, to a black audience steeped in the rhetoric of #BlackLivesMatter and the names of its recent dead.

The Birth of a Nation may be a movie about black history that black people actually go see, in other words.

And then it might win over the Academy.

That, at least, is the strategic hope implied by the advertising. There are no guarantees. And none of this means it will be a good movie, or even an interesting one — in fact, critical support is already waning. But critics and audiences want different things — the Academy’s interests are nested somewhere in between. It will be mandatory viewing, regardless, and so will its returns, if only to know whether Birth of a Nation’s appeals to our current political moment can counteract black audiences’ fatigue with art about slavery and the Civil War, or “black movies where niggas getting dogged out,” as Snoop Dogg recently put it. By speaking the current language of protest and agitation, by exposing its own agitation with American history as much as with Hollywood history, The Birth of a Nation is demanding to be seen.