The Freak Battles Nature

Tim Lincecum used to obliterate the laws of physics. Now he’s fighting them as he attempts to revive his career.As Tim Lincecum sat answering questions in the Oakland A’s visiting dugout earlier this month, wearing strange colors but surrounded by familiar faces, the assembled media swooned. This was odd to witness. Sportswriters are not known for their enthusiasm, yet there everyone was, surrounding Lincecum a day before his first big league start in nearly a year, smiling bigger and leaning closer than is typical for a pro scrum.

"Wow," said one reporter. "Tim Lincecum."

"Crazy to see him, huh?" said another.

"Awww!" a columnist would say in the clubhouse the next day. "Look at his little haircut!"

He was back: back in the big leagues after a year sidelined by injury, and back in the Bay Area. This time, however, the former Giants icon was making a road trip with the Angels, his new team. Three months ago he’d been out of baseball, unsigned, training in Arizona without a team. Now he was on a one-year deal prorated for a little less than $2 million, ready for his first chance to lock down a return to a big league rotation. Reporters volleyed standard questions and received standard answers. Lincecum was "excited," he said; "nervous" but "confident." His return had been a "gradual process" and he felt "very lucky" to be taking the mound. After a few minutes, an Angels staffer let the reporters know their time was up; Lincecum needed to stretch. And so they began to disperse, clearing his path to the field, and with that, the two-time Cy Young winner took a deep breath, leaned forward, and … sat there. He didn’t get up. He didn’t go stretch. He made small talk with beat writers — about the weather, about his dad, about being back in his adopted home.

It was as if he wanted to linger in the dugout, luxuriating in one sliver of the daily routine he’d lost when his left hip went bad. Just above the reporters, there stood a woman wearing his old Giants jersey and a father and son sporting jerseys from Lincecum’s alma mater, the University of Washington. He wasn’t scheduled to start until the next day, but his fans had shown for warm-ups.

This is the Tim Lincecum experience in 2016: He’s no longer dominant, and it’s unclear whether he will ever again even be good, but the moment he returned to the major league ranks, he became someone who lingers over pregame mundanities, who makes reporters fawn over clichéd answers, who inspires fans to show up hours early just to watch him stretch.

After a few additional minutes of chitchat on that June 17 afternoon, Lincecum smiled and began to stand. "OK," he said. "I guess I should go stretch now." He walked up the steps and onto the field, and, for a moment, the dugout went quiet.

"Well," said one reporter. "That was an absolute delight."

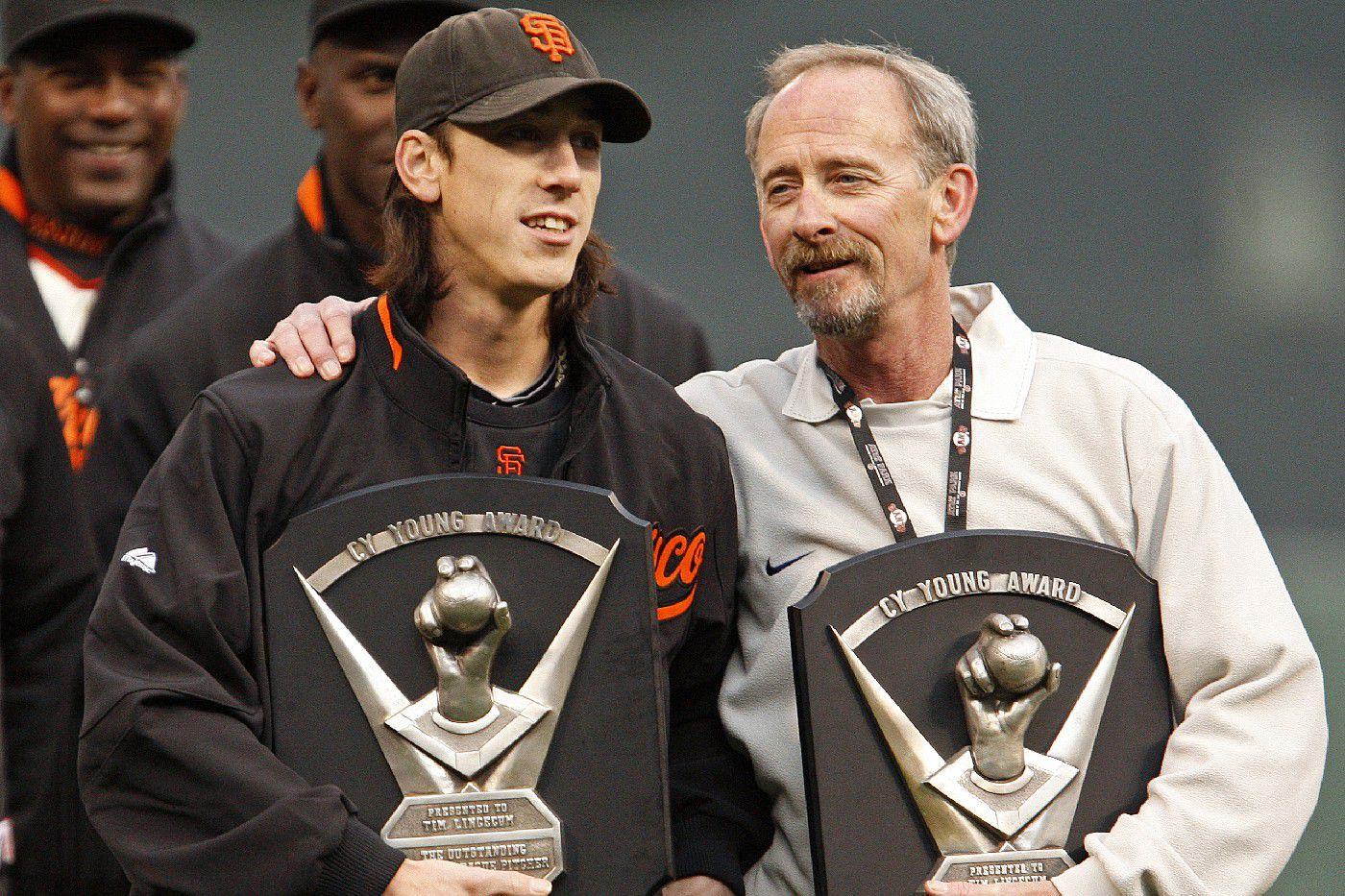

At his peak, Lincecum seemed impossible. He arrived in San Francisco in 2007 nearly fully formed, as if the Giants had grabbed some guy out of a Valencia Street dive bar, handed him a uniform, and watched him blossom into a perennial All-Star. He won the Cy Young in his second season, then won it again the next year. He was a miracle of physics: 5-foot-11 and 170 pounds, with a fastball that lived at 95 and sometimes touched 98.

His father had engineered his mechanics, and coaches knew not to tinker with the machine. Delivery: quick. Stride: long. Release point: the exact same for the fastball as for the changeup or curve. Lincecum led the majors in strikeouts per nine innings three years straight. He made four All-Star teams. And he did it all with such quiet charm, without ever showing the ruthless intensity that burned underneath. He looked completely human, but threw as if trying to redefine the limits of the species. Physically, he was "The Freak" — Allen Iverson in cleats. With Mission District detachment and Haight-Ashbury hair, Lincecum was so perfectly San Francisco that when he got busted for pot, Giants fans responded by wearing "Let Timmy Smoke" T-shirts. Here was Tim Lincecum, the city’s flamethrowing stoner king.

And then, in 2012, his heat began to fade. Velocity dropped. Pitches fattened. Baseball’s most electrifying ace began to seem like just another pitcher.

Lincecum’s pitch speed sunk. His ERA nearly doubled as his FIP and WHIP ballooned. His once eye-popping K% dipped. The Giants remained a National League power, but Lincecum slipped down the rotation by the month, coming out of the bullpen in both the 2012 and 2014 World Series.

From his living room in Washington, Chris Lincecum watched his son and formulated theories about what had gone wrong. For as long as Tim had been pitching, Chris had been by his side. He’d built his son’s delivery, then tinkered with it over time. He boasted that he could diagnose Tim’s mechanical problems just by listening to him pitch on the radio. He only needed to hear the velocity and the location, he said, and he could clearly picture every detail of Tim’s pitching motion.

But after Tim reached his sport’s greatest heights, they began drifting apart. "I’ve always worn two hats with Tim," Chris said in a recent interview with The Ringer. "I’m his dad, and I’m his mechanics guy. The father-son relationship never wavered. But the baseball relationship did. He’d won two Cy Youngs. And even after two Cy Youngs, I was still on him about his mechanics. So at one point he came to me and said, ‘I want to do this on my own. I need to do this on my own.’ It was like a rite of passage, the sort of thing any son in his 20s goes through in his relationship with his father."

With his position on the Giants in increasing jeopardy, Lincecum reenlisted his father before the 2015 season to ask for help rebuilding his mechanics. "That was tough," Lincecum said that winter. "It’s like a kid going home with a bad report card and saying, ‘I tried to do it on my own.’ I had to apologize."

Chris believed he had diagnosed his son’s struggles. "Physically," he said, "Tim just wasn’t right. You could tell because his velocity dropped across the board. If it’s just the velocity on his fastball, then maybe you think he’s just losing strength. But it wasn’t just the fastball. His curve dropped, his change, his slider. When you lose that much velocity on every pitch, something is wrong." Chris studied his son’s delivery. "It still looked good to the naked eye," he said. "He still looked like a ballerina."

Lincecum had a torn labrum and an impingement in his left hip. He’d carried pain in both hips for years, but had pitched through it. "A doctor told us that his hips had been deteriorating since he was 9 years old," said Chris. "It was like a cyst, building for years. We asked, ‘Was it pitching? Was it because of the way he throws?’ He said, ‘No. He could have been a mailman, and this was always going to be an issue.’"

Lincecum’s velocity had never been a miracle; it had been the product of extreme athleticism unleashed by a delivery that made use of his entire body. As his hips continued to deteriorate, his upper body functioned the same as it always had, but his lower half no longer stayed on the perfectly calibrated track he and his father had spent years building. "His foot would be facing toward first base when he’s throwing toward home," Chris said. "Then you have his back trying to course-correct and make up the difference." He continued: "So you watch him, and you can see it. He’s trying to compensate for the pain, and his foot and his hip are opening up at the same time."

"When everything is right," said Chris, "his front foot lands, and it’s like the pole landing for a pole vaulter. It bends from the bottom up. Well, at this point he’s not getting that. When he’s got his hips open from his crotch to his shoulder, then he’s throwing purely with his arm and his shoulder. It’s impossible to get leverage. It’s like throwing a punch with Jell-O. You’ve got nothing."

Lincecum lasted only 15 mediocre starts in 2015 before a line drive to the elbow put him on the disabled list. Only then did Lincecum decide to deal with his hip. He underwent surgery that September, and when the season ended, he began rehabbing in Arizona. His contract expired, and Lincecum entered free agency, injured and unattached. For the first time since arriving in the majors in 2007, Lincecum was no longer a fixture in the Giants’ plans. Down in Arizona, he worked out on his own.

"It was frustrating for him because it’s so monotonous," said Kyle Parker, Lincecum’s college teammate, who now works with the agency that represents Lincecum and spent the winter with him in Arizona. "In those early stages of rehab, you don’t even feel like you’re doing anything. You’re spending hours every day just laying there like a dummy. The therapist is doing all the work. It’s hard for someone like him to just lay there like that every day." In January, Lincecum invited his father down to visit and help him train. Chris expected to stay in town a few weeks. He was there for four months.

"Once we started doing bullpen sessions," said Parker, "I remember one day when I felt like he really had it going. Everything is popping. There’s movement. I’m catching for him, and I’m thinking, ‘Wow, we’re really getting somewhere.’ We finish up, and he’s just furious. He’s disgusted. He can only think about the things that weren’t quite right. That’s just the perfectionist he is."

Chris spent hours with Tim each day, working to put each piece of his delivery back in its proper place. "I found out last year he really did not fully understand the concepts of leverages and delivery," said Chris. "Now, he could execute them. He’s such an amazing athlete, and he’s such a perfectionist and a hard worker, that if you told him what to do, he could always do it. And with his muscle memory — once the right motions are in place, he can repeat it over and over again. But he needs some help with the concepts."

Again, they worked together to recalibrate Lincecum’s delivery. With a repaired hip and more finely honed mechanics, Chris believed his son would be on his way to regaining his old form. He wouldn’t hit the high 90s any longer — he’s in his 30s now, and strength wanes with age — but perhaps he’d come close. "People talk as if Tim was pitching 98 all the time," said Chris. "Well, no, he was in the mid-90s and he occasionally hit 97 or 98. He can’t just say, ‘I’m gonna reach back and hit that speed,’ anymore, but as he works his way back, do I think he can be at 92, 93, 94? Yeah."

Winter passed, pitchers and catchers reported, Opening Day arrived, and Lincecum remained unsigned. Rumors circulated of a return to the Giants, but San Francisco reportedly wanted him as a reliever, and Lincecum wanted to start. So in May he invited clubs to a showcase, and in a USA soccer jersey and camo socks, he threw 41 pitches. He looked good, touching 91 mph with his fastball and showing movement across all pitches. Two weeks later, he signed with the Angels, who had already lost five pitchers to injury and were in desperate need of a fresh arm.

He spent two weeks at Triple-A Salt Lake. One night during a rehab start in Fresno, Lincecum came into the dugout, distressed. The radar gun had clocked his once-mighty fastball at 85 miles per hour. "Please," Lincecum said to his fellow pitchers, "tell me that gun is off."

Yes, Bees pitcher Kyle McGowin remembered telling him. The radar was off by two or three miles an hour.

"Man," said Lincecum. "I was really hoping you were going to say it was off by five."

Soon after he arrived in Utah, Lincecum asked players for their phone numbers so that he could join dinners and video-game sessions on the road. The Bees allowed him to stay home during games he wasn’t pitching, but Lincecum chose to remain in the dugout, working to integrate himself into a new team. "He acted like a minor leaguer," said McGowin. After his final rehab start, Lincecum could have returned home before joining the Angels on the road. Instead, he wanted to stay with the team as long as he could. "This is so awesome," pitching coach Pat Rice remembered Linecum saying about his return to the minor leagues. Lincecum seemed to care only about sharpening his own performance and feeling again the rhythms of the game.

Nearly a week later, in Oakland, Lincecum sat perched on a chair by his locker, crouched into a catcher’s stance. It was Saturday, June 18, the morning of his first start in nearly a year. He’d been anxious all morning, had barely slept the previous night. He arrived at the stadium a little after 9, hoping that the feel of the ballpark would calm him. It didn’t. His left leg shook. His head bobbed. New faces wandered through the locker room. Left fielder Daniel Nava walked by, one of the few Angels Lincecum had known before he arrived.

"Daaaamn, Daniel," Lincecum said. Nava kept walking.

"DAAAaaaamn, Daniel," he said again, laughing to himself. Nava’s first name is Daniel, you see. And, well, it’s a meme.

Smiling, Nava continued to his locker. Lincecum’s eyes followed him across the room. "DAAAAAAAAMN, DANIEL!!!!!!" He laughed some more, then settled back down, eyes moving to the Iceland-Hungary soccer match on TV. First pitch was in a little less than three hours. It was going to be a long wait.

Outside, fans filtered into the stadium, many in Lincecum’s Giants jersey, no. 55. There was Lauren Lorenz, sitting just above the dugout by herself, holding a ticket to Lincecum’s first no-hitter that she was planning to ask him to sign. "I’m obsessed," she said. There was Michael Johns, a driver for the Giants who came across the bay to see the man he once drove all over town. "I consider him a friend," Johns said. "Not many guys — athletes or not — are as down to earth and cool as he is." And then there was Len Hom, a lifelong Giants fan who said, "This is so bittersweet. He should be in orange and black. But I’m still so happy to see him back."

Lincecum took the mound to cheers, even in an opponent’s ballpark. He came out dealing, inciting weak contact and getting outs from a defense that seemed in perfect position on every ball in play. Yes, there were reasons for concern. He needed 98 pitches to get through six innings. He struck out only two hitters. And his fastball averaged 89.5 mph, well below his power-pitching peak. Struggles seemed sure to come, and they did in his second start, when Lincecum lasted just three innings.

During his son’s rehab this winter, Chris Lincecum realized something about why Tim had called him down to Arizona. Their days were ruled by the rhythms of an athletic relationship long-ago formed: Chris as the coach and the painter, Tim the athlete and the canvas. But there was more than that. "I realized," said Chris, "even more than the mechanics stuff, he just needed someone there with him." He continues: "What he really needed was someone there pulling for him, so he’s not all alone."

As Lincecum walked off the field in Oakland, the crowd rose — not just visiting Angels fans or Giants fans who made the trip across the bay. Even the A’s fans stood, clapped, and screamed. This was the guy who captivated the baseball world over the last decade, who left sports reporters hanging on his every word. He’d lost so much of what made him great, but had become even more compelling in his quest to reclaim it. Now, instead of obliterating the laws of physics, Lincecum had to battle them.

He walked to the dugout, head down, noise washing over him. The cheering continued. "I’m not pumping the cheese anymore," Lincecum said after his debut, hunched in his seat at the press conference, wearing a green hoodie and wet hair. But even without the heat, the love remained. By struggling against the limitations of his own body, Lincecum had reminded us that The Freak had always been made of the same raw materials as everyone else.