June 25 marks the 20th anniversary of Reasonable Doubt, Jay Z’s first album. To commemorate, we’re celebrating with Jay Z Day.

Jay Z, the Sidekick Turned Kingpin

The dubbed cassette arrived at his Mississippi home via FedEx from New York. "Reasonable Doubt" was carefully handwritten on the label. For its recipient, Charlie Braxton, Jay Z’s 1996 debut would also represent a personal milestone. Braxton’s review of the record would be his first byline in The Source.

At 34, Braxton was hardly a writing novice. He had already been published in hip-hop publications like Rap Pages and 4080; in his other life, he wrote and performed poetry. But The Source was the big time. In ’96, the magazine was the undisputed rap bible — its reviews section, the gospel. So when Source editor-in-chief Selwyn Seyfu Hinds asked Braxton to write about Reasonable Doubt, it was both an opportunity and a challenge. "I think Selwyn wanted someone with fresh ears," Braxton says now.

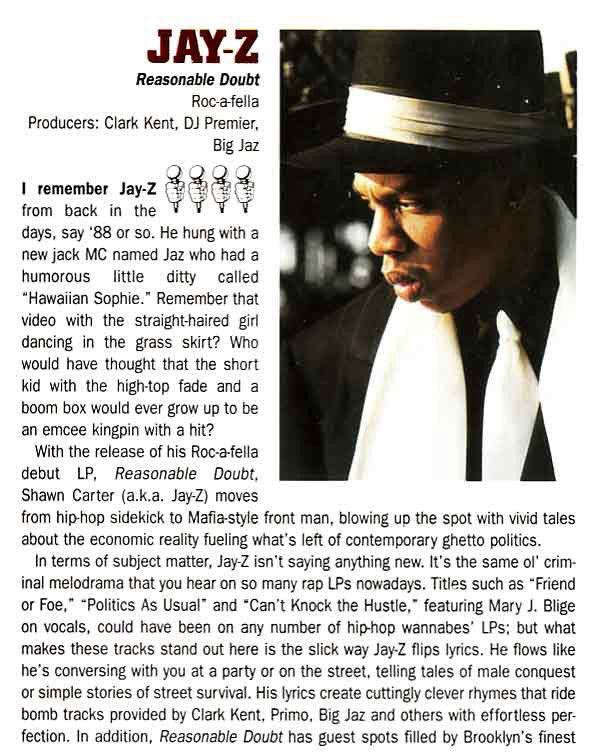

"Fresh ears" presumably meant those belonging to someone from outside the echo chamber of NYC. But though Braxton grew up in the Deep South (and never left), he considered himself an expert on East Coast hip-hop. In 1996, Jay Z was a New York indie artist worth critical attention, but without the national buzz of 1994’s famed rookie class of Nas and Biggie. "I knew Jay Z, initially, from his connection to Jaz," says Braxton, referring to Jay’s Marcy Projects mentor. In fact, his Source review opens with a slightly patronizing reference to "Hawaiian Sophie," the comically bad Jaz-O single whose video features a very young Jay Z in 1989: Who would have thought that the short kid with the high-top fade and a boom box would ever grow up to be an emcee kingpin with a hit?

Braxton had a ritual before reviewing albums: "Turn off the lights, close my eyes, put on my earphones, and listen through it five times." (As opposed to: hear a few 30-second snippets and spit out a definitive take on Twitter.) His first impression of Reasonable Doubt was not an uncommon opinion of Jay Z at the time: here was an undeniably compelling MC who was hampered by his material — the drug-kingpin fantasies that were de rigueur in mid-’90s rap and the subject of heavy backlash on prominent ’96 releases like the Fugees’ The Score and De La Soul’s Stakes Is High. Jay was talented, in other words, but a bit trite. In terms of subject matter, Braxton wrote in The Source, Jay-Z isn’t saying anything new. It’s the same ol’ criminal melodrama that you hear on so many rap LPs nowadays.

In his review, Braxton describes, from a fan’s perspective as much as a critic’s, the evolution of Jay Z: hip-hop sidekick to Mafia-style frontman. Up to that point, Jay had lurked in the shadows of non-crime-obsessed rap elders like the aforementioned Jaz, Big Daddy Kane, and Original Flavor. Therein was the disconnect. Without knowing the extent of Jay’s real-life hustles, his Reasonable Doubt lyrical transformation could seem as jarring as the sartorial gap from Hawaiian shirts to Al Capone suits.

"The first time I listened to the album, I liked it. There were a couple of records I didn’t like," Braxton says. "Politically, I had problems with the misogyny, and I still think that ‘Ain’t No Nigga,’ sonically, does not belong on that record. It fits on The Nutty Professor soundtrack." Despite those reservations, Reasonable Doubt earned a decent four mics — based on an aggregate rating from the reviewer and The Source staff — on the magazine’s famous five-mic scale. (Two years later, Braxton would pen a five-mic review: Outkast’s Aquemini.)

"A lot of people hated me for the Reasonable Doubt review," Braxton says. "Jay Z was mad at me, too." In 2002, The Source retroactively granted Reasonable Doubt the coveted five-mic status — which was better never than late, according to the artist himself. "Debut’s a classic, first album, four mics," he rapped in 2006 on "44 Four’s." "Shoulda got a five, but niggas lack foresight."

Jay Z, the Would-Be Heir to the Throne

In the August 1996 issue of The Source, Braxton’s Reasonable Doubt review appeared side-by-side with the review of that season’s other major rap release: Nas’s much-anticipated second album, It Was Written. Back then, the two albums were inextricably linked; the reigning critical champ and a promising contender. In retrospect, it was inevitable that they would one day clash.

Likewise, the two LPs appeared together in the summer issue of indie rap mag Ego Trip, this time in a combined review by "Warren Coolidge," who you may know now as esteemed hip-hop pundit Elliott Wilson. Another illustrious Ego Trip alum, Jeff "Chairman" Mao, can explain in vivid detail how he and and his colleagues first acquired advance copies of both albums. (Suffice it to say it’s a Queens caper that involves elevated trains, Hydra Records, and a bootleg-wielding connect dubbed "Haitian Mike.")

The media hype around It Was Written’s release was pre-internet authentic: it had the unbridled, laser-like intensity of obsessive people with very few distractions. Over two years had passed since Nas’s universally beloved debut, Illmatic (five mics in The Source, natch). The Ego Trip boys could hardly drop its sequel in their tape deck fast enough. Imagine that anxious room of writers now, as It Was Written’s opening skit plays …

"I remember thinking," recalls Mao, "‘Man, this is not a good sign, the way this album is starting.’" The hammy intro bleeds into the Sting-sampling "The Message," followed by the Eurythmics-interpolating "Street Dreams." Good songs, both — in fact, classics today — but in the room there was a single prevailing thought: "Not Illmatic." Nas, they lamented, had gone commercial. He was a victim of the impossibly high standard that he had set for himself.

The listening session ends; the room, deflated. But Haitian Mike has a surprise: "Oh, and by the way I got this Jay Z album, too." Eyebrows rise, though there is little urgency to listen to it in the moment. The Nas wounds are too raw. But later that night, Ego Trip members would reassemble to preview Reasonable Doubt. The comparison was immediate and stark.

"Hearing it coming up after the Nas album, which was so disappointing, it was like, ‘This is what’s important now,’" Mao says. "This guy’s shit is basically fulfilling the promise of what we were hoping for from Nas — not exactly doing what he does, but something that’s an evolution of these styles and moving towards something new."

That night was the first time that Mao heard the entire Reasonable Doubt album in sequence, but not his first exposure to Jay Z. Rather than having fresh ears, you might say Mao’s were hardened, nuanced. A seasoned writer ensconced in the hip-hop industry, Mao had already submitted a one-page profile of Jay for Vibe, The Source’s main newsstand competitor. (Vibe published Mao’s piece in its August 1996 issue, but never officially reviewed Reasonable Doubt.) Knowing Jay’s roots with Jaz and Original Flavor, Mao had pitched the up-and-coming artist based on the strength of the album’s first single, "Dead Presidents." "The beat itself was really compelling — the very somber piano — and it had the Nas hook," says Mao. "His storytelling compelled you to want to follow his narrative."

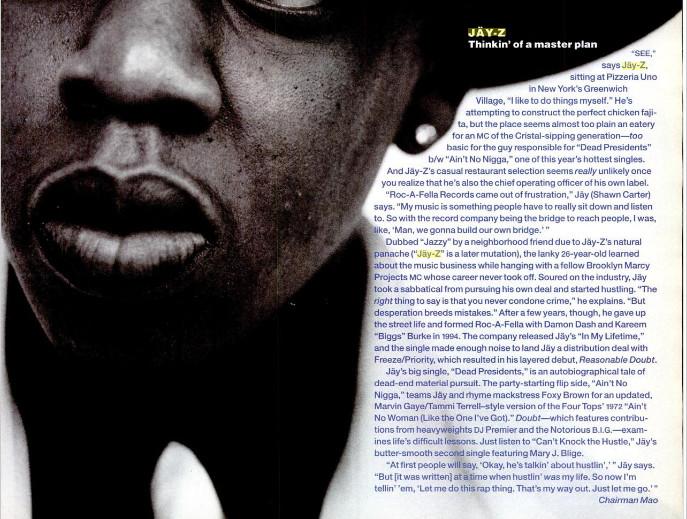

For Mao’s Vibe story — in which Jay’s name appears with both hyphen and umlaut — he visited the original Roc-A-Fella Records office on John Street in the Financial District, where he was played a sampling of tracks. From there, Mao and Jay went to chat at the rapper’s favorite restaurant: Pizzeria Uno. As he munched on chicken fajitas, Jay very clinically laid out his game plan for success. Failure had informed him. "He saw somebody come out of Marcy Projects, sign to a major label, and not be commercially successful," Mao says. Jay Z, along with his business partners Damon Dash and Kareem Burke, exuded an arrogant cool that belied their newcomer status.

Nas was also projecting arrogance in 1996. Battery-packed by Puffy, B.I.G. was too. The difference is that they had developed that arrogance after critically acclaimed debuts lined with the pathos of poverty. Reasonable Doubt has its poignant moments, sure — the last song, after all, is titled "Regrets" — but they are the problems of a made man, not one who robs foreigners for their green cards or recalls birthdays as his worst days.

Back to that Ego Trip review: In many ways, Jay Z is the personification of everything Nas wishes to become, writes Wilson. Harsh words in 1996, insightful commentary today. But it’s important to note here: Jay Z was 26 when Reasonable Doubt came out; when Illmatic was released in ’94, Nas was barely 20 (Biggie was 22 for Ready to Die). They are peers in the way that a high school recruit is with an older, polished player who has quietly refined his game out of the public eye.

"If Jay had done an album at age 20 or 22, then it probably would’ve sounded like ‘The Originators,’" says Mao. (Read: earnest, mildly interesting, but forgettable.) "There is no way to separate the fact that he is a little bit older than these guys, and had a perspective that was perhaps broader in scope." Jay had observed what had worked with B.I.G. and Nas and tailored his own persona accordingly. "He represented an interesting midway point between the two styles," says Mao. "He had that Brooklyn cool but also had the analytic, writerly side to him."

Beyond the perspective of the MC, there’s a musical maturity to Reasonable Doubt that has arguably allowed it to sound less dated than Illmatic or Ready to Die (though very, very few would rank it above those two albums). To defend that argument, it’s not the artists’ ages but the time period between their releases that is most informative. The cacophonous chanted choruses of 1994 slowly morphed into melodic Mary J. Blige (or Lauryn Hill or 112) hooks two years later. Primal passion was still rewarded, but it was being trumped by a kingpin’s placidity. Less "real hip-hop," maybe — but more sophisticated as well. As Puffy’s avatar, Big was at the forefront of this transition; Jay Z took it even further. In 1996, Nas was seen as hustling after a bus that his Brooklyn counterparts had already boarded.

Which leads to a final, cold prophecy from Wilson on Jay and Nas, in the closing to his Ego Trip review: When all is said, done, and divvied up, [Jay Z] will probably make more money.

Jay Z, the Hustler’s Hero

Jay Z and his partners famously funded his musical ambitions with that catchall financial category known as "hustling money." They paid for their own videos, sent bottles of champagne to DJs, and bought full-page magazine ads. In the developing hip-hop cities outside of NYC and L.A., this type of DIY approach was the default method. But in New York, the center of the hip-hop industry, over-the-top salesmanship could be perceived as forced and crass. Nas and Biggie followed the old-school protocol to become media darlings: get discovered by someone with clout, generate an organic groundswell, and then let the big bucks of a major label do the heavy promotional lifting.

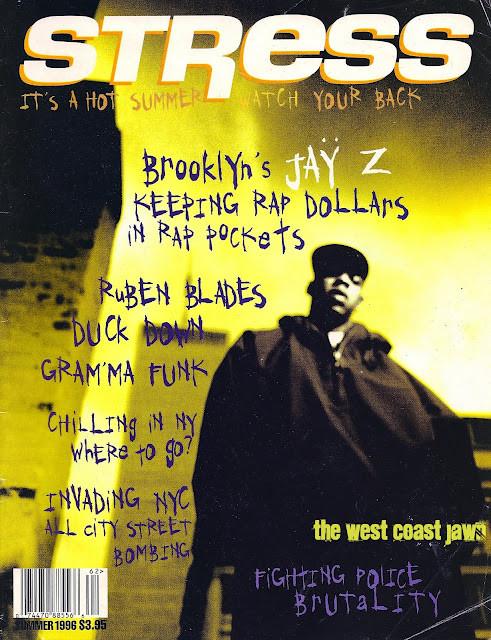

In that sense, Jay Z was a rank outsider — which is why it’s fitting that his first magazine cover was not for The Source or Vibe, but instead for the underdog publication Stress. Jay Z appears on the front of the magazine’s third issue, released in the summer of Reasonable Doubt (and currently available for $350 on eBay). "Stress was a diverse, different perspective on hip-hop media than Source and Vibe, which we thought were bougie," says founding editor-in-chief Alan Ket, who later helped create Complex. "We wanted to be rawer than those cats — and Jay was that."

As was the norm for Stress, the Jay cover was orchestrated by friends of friends, not by maneuvering label politics. "It wasn’t Columbia Records or Bad Boy trying to hit us to do a story," says Ket. "It was more like, ‘What’s happening? Let’s get the streets, the people that are really bubbling.’ And I think that helped separate us from everybody else, and also didn’t lock us into being some industry rag, which we thought a lot of the other magazines were at the time."

Jay Z was not yet a star, but his music was starting to bubble in NYC. "We believed in him, his ability, and his artistry and that he was representing for New York in a way very similar to what Biggie represented," says Ket. "There was a ’90s sound that Jay fit into, he was just a bit flashier, flyer version of that. It sounded authentic."

More importantly, and most authentically, Jay and his team were unapologetic hustlers — an affront, perhaps, to the establishment, but a common bond with Stress. "We were working such crazy hours to just figure out publishing because we were so new to it. For us it was a hustle," says Ket. "Because we had a pretty street mentality in the sense that we admire people who were hustlers, Jay Z’s story really resonated with us."

According to Ket, Dame Dash actually offered to buy Jay’s way onto the Stress cover for $10,000 — a fee which Ket declined then but now regrets leaving on the table: "I was stupid and naive, I should’ve taken the 10 stacks." Still, while one could imagine other magazine editors blanching at Dame’s attempted bribe, to Ket and his team it was part and parcel of Roc-A-Fella’s charm. "He’s a small entrepreneur, it’s a small business," says Ket. "Let’s support a black-owned business with people that look like us, our peers."

The accompanying cover story, written by Asondra R. Hunter, extends Jay’s hustler-turned-good mythology: Robin Hood, capitalism, Russell Simmons, and a "vision of federal agents rifling through his Park Slope apartment." Also, on paper for the first time, the birth of this soon-to-be-integral bit of trivia about Jay Z’s recording career: "I keep telling everybody that this is my first and last album," he tells Hunter. It’s very Jay Z, that quote — a calculatingly indirect way to make a direct statement. Many years later he’d expound on the idea in his memoir, Decoded: "When I made my first album, it was my intention to make it my last. I threw everything I had into Reasonable Doubt, but then the plan was to move in to the corner office and run our label."

Even before his debut album was in stores, Jay Z was very much in control of his own narrative and the direction of his music. He’d enter — and threaten to leave — on his own terms. Today, that’s a given for any recording artist; in 1996, it was rare air for an aspiring rapper. To fans and critics alike: perhaps we didn’t really appreciate it until his second one came out.