One weekend last month, hundreds of expensively dressed Los Angeles teenagers stood in line on Fairfax Avenue, sweating.

“I got here at 10 p.m. last night. I put chairs down, and then I left, went to eat, and got a blowjob,” Avi, 17, rattled off on Sunday afternoon. “Then I came back here around 4 in the morning to check that my chairs were still here. I went to sleep in my car, and then I went to Taco Bell — I was hungry as fuck. I got three cheese quesadillas and a shitload of sauce — bro, I was drinking the sauce. I came back here around 9, and had a good nap. I was 16th in line and it took me an hour and a half to get in.”

This is the Bape-patterned heart of Los Angeles’s streetwear scene, and these lineups happen more often than you’d expect. Supreme’s only West Coast store is here; Odd Future’s since-closed pop-up sat on the same block. But this weekend was something different, something heightened: Kanye West was here to sell merch. (At least in retail spirit: Kim’s Snapchats put the couple in Rome at the time.) At 7:15 PT on Friday night, West announced a “pop-up shop”; by 8 p.m., the streetwear-hounding teens of Greater Los Angeles had congregated.

Avi and his cohort were waiting for access to a whitewashed space selling tees and hoodies, jackets and hats and one-piece swimsuits, priced from $45 (the embroidered dad caps) all the way up to $400 (the customized denim jackets). Everything bore taglines and lyrics from West’s album The Life of Pablo — “I Feel Like Pablo,” “That’s Just the Wave” — rendered in a chunky gothic font. The designs were exclusive to this weekend and location, but decidedly of a piece with the Kanye ecosystem. West had sold different iterations of these same clothes — royal-blue tees rather than seafoam green, washed denim jackets instead of ghostly bleached versions — in March at a prior pop-up in New York. A month before that, he had sold them at his concert-cum–fashion show at Madison Square Garden, stocking them in diamond-plate booths built to his exacting specifications. Each time, the kids — and by and large, the crowds have consisted of kids — came out. On this weekend in L.A., the kids came out again. They were hungry for merch, and Kanye was ready to feed them.

The scene was like Kanye cosplay, funded by teenage savings and mom’s credit card: Yeezy Boost sneakers, shredded denim, extra-long and layered tees. Some wore West’s prohibitively expensive fashion line. Others, though, wore different versions of that singular gothic-font tee: “I Feel Like Pablo” printed over the heart, a tombstone of text arching across the back.

Now, Avi strolled up and down the line entrepreneurially, clutching multiple plastic bags loaded with the goods, hoping to resell them for double what he’d paid. Girls waited patiently as their boyfriends bargained; a few Kanye fangirls did the same, as their own confused boyfriends stood around and scuffled their feet. (Think of Kanye merch as the streetwear equivalent of baseball cards: Anyone can collect it, but teenage boys are best represented.) Toward the back of the line, Avi’s wares were compelling — staring down the barrel of a six-hour wait, the exorbitant price felt worth it. As we spoke, a prospective buyer — another kid, stick-thin and clutching his own bag of merch — jumped in.

“What’s on the hat? Your seafoam hat? I’m just curious,” he said, not a little frantically. “Because on the [pamphlet with styles and prices], it says, ‘I Feel Like Pablo,’ but it was ‘Wolves’ when I got it.”

“I don’t fucking know,” Avi shrugged. His seafoam hat was buried at the bottom of the bag. “They’re a bill,” he said, “or two for $180. Ebay’s $120 right now.”

Before we performed our identities on social media, the quickest way to signify taste was by wearing your favorite band’s T-shirt. But as artists have become brands, we’ve become their avatars. Now, instead of wearing Kanye West’s face on your chest, you can literally shop from his closet. Consequently, the traditional concert-merchandise portfolio of logo-adorned tees and hoodies expanded to include those seafoam hats, sure, but also artist-branded perfume and temporary versions of your favorite musician’s tattoos.

“Merch is definitely not just T-shirts anymore,” explains Alyssa Tobias, the creative director for the Araca Group, a merchandising and production company. She’s worked on everything from old-school Rolling Stones tees to Ellie Goulding–branded leggings, and notes that fans are improbably excited about weirder and wilder merch. “The branding is at another level,” she says. “Denim jackets, bombers, socks, custom hats: Everything is really down to customization. The color of thread, the fabric makeup, the length of the shirt.” Any artist’s merchandise always consists of the bread-and-butter: dirt-cheap screen-printed tees upsold for huge margins. But collectible stuff? Limited-edition styles that borrow heavily — in both design and distribution — from graphic-based streetwear? That’s new.

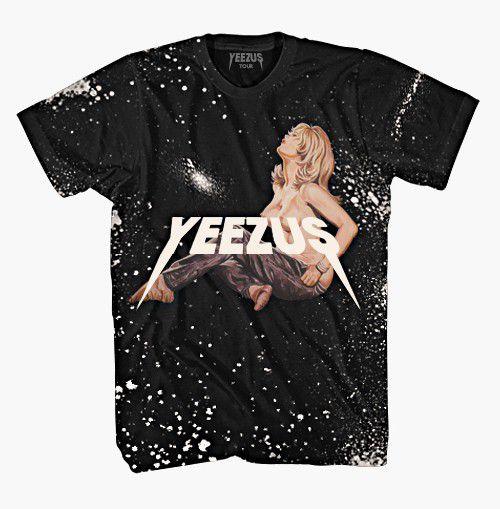

The change has been gradual, but its inflection point came in 2013, when West enlisted his Donda brain trust to come up with Yeezus tour merch that riffed on golden-age metal tees. Art director Joe Perez whipped up a logo an inch to the right of Metallica’s and cribbed bad-trip-in–Joshua Tree illustrations from motorcycle-owning artist Wes Lang.

“The tour is a spectacle,” Perez says. “So we look at the themes of the album and whatever inspired the music. And then we’ll look at the actual tour, the production and the stage design and the narrative, and we try to translate all that to merch.” (Perez recently wrapped his tour of Donda duty.)

In the case of Yeezus, a Connecticut hardcore band of a rap album followed by a Jodorowsky film of a tour, metal tees with headdress-wearing skeletons (and one rather controversial jacket) fit the bill perfectly. The Yeezus merch — a half-dozen illustrated, tie-dyed, and speckled tees sold for $40 — became canonical for a certain stripe of fashion fan. Aftermarket tees from the collection change hands for hundreds of dollars, and have spawned a legion of imitators.

But sought-after merch is no longer the exclusive property of Kanye West, who could make hypebeasts line up for Yeezy-branded dog sweaters. Beyoncé turned a never-even-happened police boycott into a “Fuck tha Police”–style tee. Rihanna customized the trending dad hat, and Future made high art of No Limit Records’ marbled-eyesore house style. And 2 Chainz realized that successful merch would meet its teenage consumers halfway: “I keep the youth around, and I surround myself with new creative vibes,” he explained on an episode of N.O.R.E.’s podcast Drink Champs. “Urgency and impulses is in style right now with kids. Because their attention span is so short, you have to be able to entertain within a six-second or 15-second span.” Which means grabbing and repurposing imagery they already know.

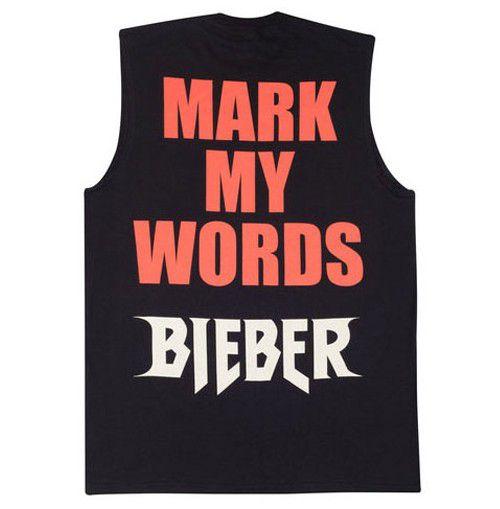

Now, no less a metal aficionado than Justin Bieber has co-opted the metal tee. For his Purpose tour, Bieber employed West pal and fashion designer Jerry Lorenzo as a sort of style tutor. Over the last year, Bieber started wearing clothes from Lorenzo’s Fear of God line (extra-long tees, ripped-up sleeveless flannels), and he tasked Lorenzo with designing the tour’s merch. The result was a series of shirts that printed the repentant pop star’s name in classic metal fonts: BIEBER: BIGGER THAN SATAN. The irony was exquisite, the clothes improbably hyped. When Bieber opened his own pop-up at VFILES, New York’s bleeding-edge purveyor of meme-based high fashion, it was mobbed in equal measure by shrieking Beliebers and scowling, Yeezy-wearing fuccbois. It was a coup: One of the world’s biggest pop stars won over the internet’s most discerning style hounds. All styles on Bieber’s website are sold out.

So let’s venture a theory: Merch became cool when it morphed into the clothes that artists actually want to wear, and that typically remain out of reach for his or her fans. (Plenty of artists have helmed clothing lines, too; few have been successful, and fewer still manage to translate that effort into the goods they sell on tour.) This is the signature of the new wave of merch: It’s indebted to streetwear, but worn like high fashion. It gestures at one taste (maybe I listen to metal) while signifying another (I listen to Justin Bieber). It’s so comfortable in its lowbrow status that it turns into conceptual art before your eyes.

But this is about more than playing dress-up. In 2016, a musical moment defined by surprise albums and streaming services, merch serves as a marker of taste, indexes your web fluency, and provides a much-needed revenue stream. Kanye proudly proclaimed on Twitter that his first Life of Pablo pop-up grossed a million dollars; it wouldn’t be crazy to assume that the second was similarly successful. But dollar figures aside, West’s Pablo merch has become as iterative and responsive as the social media moment that produced it.

Let’s start with the single tee that serves as the source code. West has been wearing some version of the shirt since March 2015, when he commissioned the Los Angeles–based artist Cali Thornhill DeWitt to make it. (West wore it to the much-lampooned launch of Tidal.) Kanye, Perez recalls, was introduced to DeWitt’s work by Virgil Abloh, another Donda “creative” and the mind behind high-end streetwear brands like Pyrex Vision and Off-White. It’s a black, long-sleeved tee that reads “Donda” over the left breast and “Tell Nori About Me” across the back, a tribute to West’s late mother. DeWitt has been making variations on the tee — itself a take on the shirts that Los Angeles’s Chicano community makes to celebrate lost loved ones — for half a decade. That gesture, a sort of loose appropriation and repurposing, has been a constant in hip-hop as long as there’s been hip-hop. It’s also an ideology native to the internet.

West didn’t enlist DeWitt just because he liked the design. As Perez tells it, they picked DeWitt because his work lent itself to a digital-first world of memes, hashtags, and endless customization. “If you look at the album art [for Pablo], it was focused on a graphic style,” says Perez. “People could take it and make it their own, using Snapchat and social media — they’ll take album art and make memes out of them. We saw that with [the video for Drake’s] ‘Hotline Bling,’ and we saw that with the Pablo album cover. So we took that idea and worked with text-based ideas, which is where we found Cali DeWitt.”

DeWitt provided an infinitely tweakable template. The style is immediately identifiable, but restricting certain colors and phrases to specific times and points of sale pushes the shirts from everyone-gets-one merch to line-up-for-six-hours-and-we’ll see hype. It’s a strategy borrowed from, among others, Supreme. The ultra-coveted skate brand is probably the only other fashion company that can generate the same sort of down-the-block, teen-heavy adoration that West does — and has managed to do so for 20-plus years by pioneering the model of endless and narrow tweaks to the graphic tee formula.

But the merch strategy isn’t limited to just tees. Flipping Gildan blanks is great business, but the margins are even better on a bomber that you can sell for $350, or a vintage denim jacket that retails at $400. Fans are willing to go further afield, says Araca Group’s Tobias, and social media allows the artist to meet them there: “The top sellers on most of our product lines are the most fashion-forward. T-shirts are still the bread and butter. But it used to be that the things you’d sell into a typical music chain retailer would be things that were in two years ago. It’s not really like that anymore, with social media and Instagram. Artists are able to post their merch with pride — and people are seen out ‘in fashion’ more.” Merch is an imperative for just about every artist, but it’s become increasingly clear that slapping a tour photo on a tee won’t cut it.

And as merch begins to resemble fashion, the artist-run line seems poised for a return. This isn’t Andre 3000’s Benjamin Bixby. Instead, the new-wave artist line looks a lot like … well, merch. Take OVO: Drake’s onetime blog has birthed a clothing line that, in its reworking of classic logos and styles (graphic tees, fleece hoodies that call to mind nothing so much as the Gap), occupies the middle ground between Kanye’s step-and-repeat Pablo goods and Bixby’s historical fetishism. It also looks a lot like the cozy staples that Drake usually wears. Which makes the equation simple for his fans: You won’t have to wait hours in line to get the stuff — that’s what Drake’s limited-edition Jordans are for. Instead, this new wave of merch takes the standard sports-fan approach — this is who I root for — and folds it into an established style that marks its wearer as in the know. You’re not wearing Drake’s face. You’re wearing his favorite sweater.

In November 2011, the teenage anarcho-rap collective Odd Future opened their own pop-up store at 410 North Fairfax Avenue. This is the same stretch of Streetwear Central where Kanye would go on to sell his Pablo merch. It’s also across the street from Supreme, the only thing that Odd Future care about more than giving offense. The goods were simple and stupid and extremely cool, in the Supreme tradition: in this case, limited-run Christmas-themed tees, of all things. “One With Nutcrackers (Super Limited) And A One With A Horny Gingerbread Man.”

Which brings us back to Kanye. It’s well established that, by now, he is better at — or at least more interested in — producing other producers than he is at producing songs. Other artists do this, too — Beyoncé’s recent gestalt is the tasteful integration of cult artworks into her seamless whole. But with Kanye, the seams always show — he’ll give over an entire track to a poorly mixed SoundCloud banger and literally shriek about his business dealings for the whole world to hear. The effort is apparent, but it’s also worth it — which is how you wind up with a tour based on a mountain, teens waiting in line for tees that look like Chicano memorials, and an album cover by Belgian artist and Raf Simons collaborator Peter De Potter. The idea is to create as large a field of gravity as possible, to pull in everything that Kanye deems dope, and to eject a synthesized version — all with maximal effort and maximum tweeting. It’s the Kanye Cool Machine: Supreme + Odd Future + the Antwerp Six + the Kardashian family’s Dash stores = Kanye’s Pablo merch.

West has spoken frequently about wanting to take his fashion as mass as his music, to make a pair of Yeezy Boosts for every kid in every mall. This is a tall order when you’re hawking $500 sweatpants. It’s a lot easier when you’re selling $50 tees. From this angle, “cool merch” isn’t just a best business practice — it’s beginning to look subversive and democratic. Cool merch will not fundamentally change any lives; “raising everybody’s taste level” is a campaign plank only on the Kanye 2020 platform. But the Kanye Cool Machine seems to have worked out some of its kinks (if not all of them) and set a streetwise blueprint for concert merch. If Avi and the rest of the teens on Fairfax are any indication, we’ll all feel — and look — like Pablo soon enough.