Hosts

About the episode

Ken Burns—the award-winning filmmaker whose documentary films and television series on American history include The Civil War (1990), Baseball (1994), Jazz (2001), and Country Music (2019)—joins the show to talk about the American Revolution and the art of storytelling.

If you have questions, observations, or ideas for future episodes, email us at PlainEnglish@Spotify.com.

In the following excerpt, Derek and Ken Burns break down the real story of the American Revolution and dive into why it’s one of the most important events of the past two millennia.

Derek Thompson: As I was putting together the research for this episode, I had the feeling that the American Revolution is almost sanitized by our familiarity with it.

Ken Burns: No question.

Thompson: The broad strokes are so familiar that we lose purchase in just how radical it was, how weird it was. I mean, it is a radical act to die for a country that clearly exists. It is a much more radical and strange act to die for a country that does not clearly exist. And so for most of this interview, I want to ask you to explain the American Revolution to me, but for this first question and answer, I’d almost like you to un-explain the American Revolution to me, to jostle our familiar notions with what this thing is. So, big picture, what makes the American Revolution so strange and so radical, so unlike the clean and sanitized story of it that we like to tell ourselves?

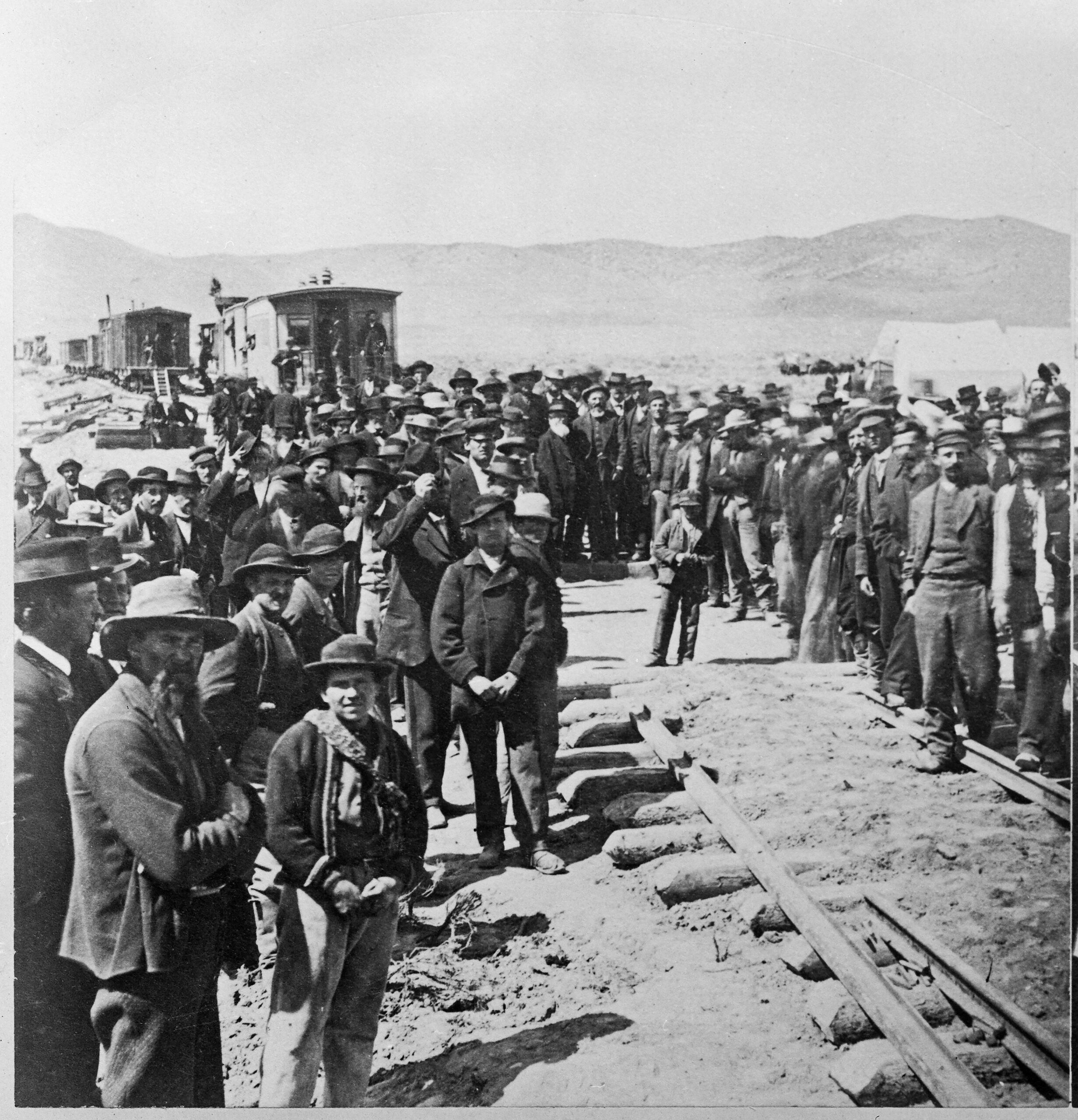

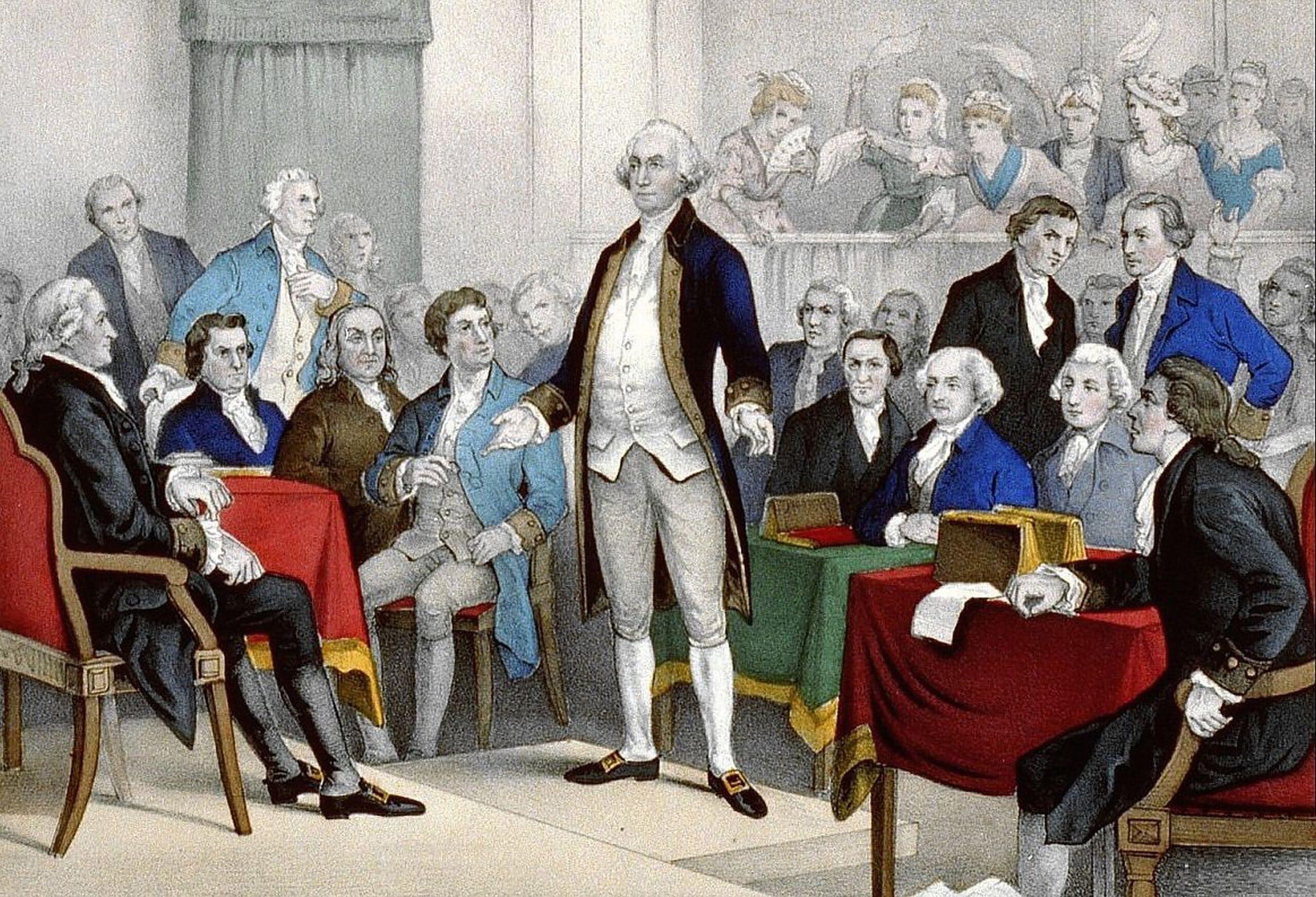

Burns: Well, I’m glad you point out that that’s sort of the way we want to tell it. It’s encrusted with the barnacles of sentimentality and nostalgia. We think it’s a bloodless, gallant myth. It’s just us against the British; that it’s great men in Philadelphia thinking great ideas, which is a huge part of it. But it’s also a very, very bloody revolution. It is an unpleasant way to die anywhere in any war, but in the late 18th century, it is particularly bad with cannon and bayonet and musket fire. This is also a civil war overlaid on top of it. A lot of Americans—at times most—are not with the program. It’s also a world war, probably the fourth world war for the prize of North America. And so what you have is, instead of this thin top level of stuff happening in Philadelphia, you find this deep, deep almost Grand Canyon of layers of people involved in it.

They could not have been more disunited, the 13 colonies. They are as different from one another—as someone said, what a scholar says in our film—as countries are. Within their midst are assimilated and coexisting Native Americans. The colonies have been superimposed over their lands or what was once their lands. At the western borders are many Native nations, each of them distinct players on a world scene for centuries that are trading partners, that are political partners, that are diplomatic partners, that are as distinct from one another as, say, France is from Prussia. You have 500,000 out of the 2.5 to 3 million people in the 13 colonies at the time of the beginning of the Revolution who are enslaved or free Black people. We represent the poorest of the colonies. The 13 colonies that we are familiar with are only half of the 26 colonies that Britain has. The other 13 are by far the most profitable. Only Virginia and South Carolina sort of turn a profit, if you will, for the [British] Empire. And of course, that profit is totally determined by slave labor.

And so you have just an amazing set of characters: not just the usual Founding Fathers, but half the population are, of course, women. And you’ve got all of these competing interests, and you end up with what I think is one of the most important events in all of world history. I’ve sort of, I guess, provocatively said that I think it’s the most important event since the birth of Christ, and only to get people’s minds disenthralled from that mythological version of the Revolution that you set at the top.

Thompson: Well, I don’t want to be a sensationalist, but it is impossible to not take that bait. How is the American Revolution the most important event in the last 2,000 years?

Burns: Well, I don’t know what I’ve … just the other night at Brown University, a scholar came up to me and said—she was French—“What about the French Revolution?” And I said, “Yeah, we sponsored it.” So I didn’t really feel, and it kind of went off-kilter in ways that ours didn’t go off-kilter. And then I’ve had people along the road—and I’ve only been saying about this for maybe a couple of months—that have brought up the black plague or the Renaissance or things like that. And I think they’re all legitimate. I would throw in: What about Gutenberg? What about Shakespeare or something like that? But I think when you come to it, everybody before, most everybody before July 4, 1776, was a subject under authoritarian rule.

A few moments after pursuit of happiness in the declaration, Jefferson said all experience has shown that mankind are more disposed to suffer while evils are sufferable. We’ve just put up with this forever. And that it’s going to require an extra bit of effort to overcome the specific gravity of that condition and to be a citizen, this new thing, and that’s going to require all the virtue. That’s what pursuit of happiness is. It’s not objects; it’s lifelong learning. And it’s not a thing to be had; it’s something to pursue. And out of that pursuit of lifelong learning would come some kind of virtue that would then earn you the right of citizenship, or at least that would be the ideal that the founders have. And, of course, nothing ever comes that way. But I think that’s pretty great. The Old Testament, which is well before the birth of Christ, of course, says that what has been will be again, what has been done will be done. Again, there’s nothing new under the sun. That’s Ecclesiastes.

I think that’s right. Human nature doesn’t change. And we can find today the same degrees of venality and virtue in our population as we can find back in the revolutionary set and indeed back in the biblical set. But I think for a little bit, there’s something new under the sun. And I think that’s what gives the American Revolution its senses. The scholar says, Jane Kamensky says in our film, this sense of possibility, even for people who didn’t have ownership of themselves, that we were letting in some pretty big ideas. And that, combined with just the mind-boggling length and scope and brutality of it, is what makes it, to me, just endlessly fascinating.

And you use the word “purchase,” and I think that’s really, really an important word. Where do we find connection to this origin story? Where do we find a real, genuine, authentic connection to something that we have so sanitized? And that I think is the rub. And for us, it was just a big, big, gigantic learning curve and 10 years of just trying to get it right; understanding all of this new scholarship; understanding, finding where the paintings and the drawings and the maps were; and to try to put it all together into a coherent narrative that has not just a top-down story of founders with a single third-person narrator but a chorus of more than 400 individual voices read by, fortunately, some of the finer actors in the world today bringing to life not just those founders but the scores of other characters who are by no means subsidiary and in some instances central to understanding what actually took place in the Revolution.

This excerpt has been edited and condensed.

Host: Derek Thompson

Guest: Ken Burns

Producer: Devon Baroldi

More Plain English Episodes on History