Plain English With Derek Thompson

Plain History: How the Transcontinental Railroads Built the Modern World

Hosts

About the episode

Today’s pod is about the economic story of the moment. It’s about new technology that supporters claim will transform the U.S. economy, an infrastructure build-out unlike anything in living memory that demands enormous natural resources, fears that corporate giants are overbuilding something that can never return its investment, an uncomfortable closeness between corporations and the state, fears that oligarchs are screwing the public to generate unheard-of levels of private wealth.

Just a small catch. This show isn’t about the present or AI in 2025. It’s about the railroads and the late 1800s.

To be sure, everything I just said could plausibly be the introduction to a podcast about artificial intelligence. Last quarter, the growth of AI infrastructure spending—on chips, data centers, and electricity—exceeded the growth of consumer spending. The economic researcher and writer Paul Kedrosky has written that as a share of GDP, AI is consuming more than any new technology since the railroads in the late 1800s.

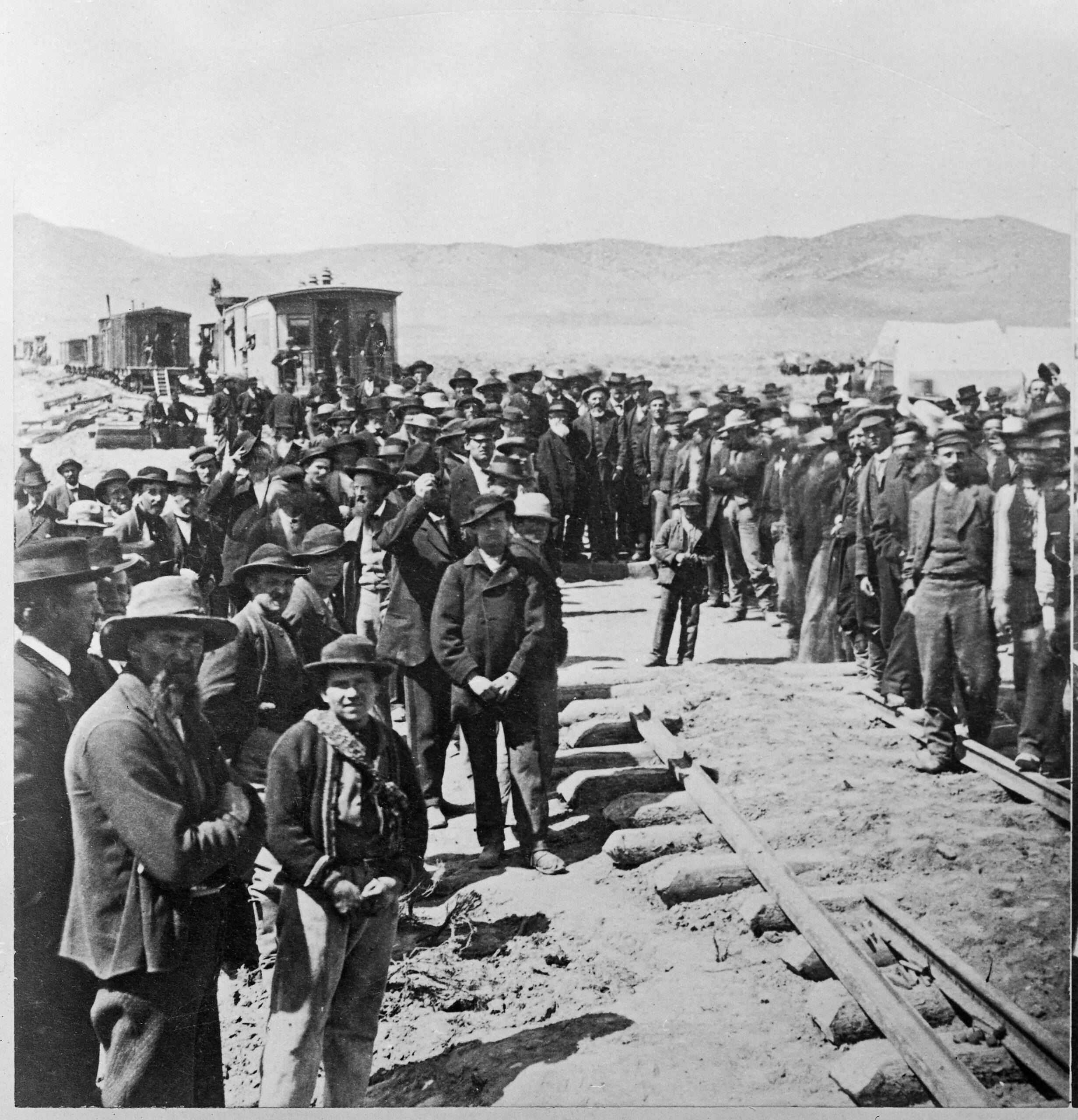

There is no question that the transcontinentals transformed America. They populated the West; practically invented California; turned America into a coast-to-coast dual-ocean superpower; revolutionized finance; made possible the creation of a new kind of corporation; launched what the historian Alfred Chandler called the managerial revolution in American business; forged a new relationship between the state and private enterprise; minted a generation of plutocrats, from Jay Gould to Leland Stanford of Stanford University; galvanized the anti-monopoly movement; and completely reoriented the way Americans thought about time and space.

“The transcontinentals … came to epitomize progress, nationalism, and civilization itself,” the historian Richard White wrote in his epic history of the transcontinentals, Railroaded. But he continued: “They created modernity as much by their failure as their success.”

Today’s return guest is Richard White. Our acute subject is the transcontinental railroads and the 19th century. But our deeper subject is the nature of transformative technology and the messy business of building it.

If you have questions, observations, or ideas for future episodes, email us at PlainEnglish@Spotify.com.

In the following excerpt, Derek talks to Richard White about the rise of—and corruption behind—the transcontinental railroads.

Derek Thompson: I want to start with the big picture before we tell the story of the transcontinental railroad chronologically. I will confess that it was my understanding of the transcontinentals, before reading your book, that this was a classic American success story—not just in the obvious way that we knit the country together, populated the West, made America a two-ocean superpower. But also, I had read Alfred Chandler’s classic The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business, where he argues that the railroad and the telegraph made possible the modern corporation, which was an impressive invention in its own right.

Your book is a pretty direct wrecking ball, both to the proposition that the transcontinental railroad was an unqualified success, and that we should see it as having invented the rational modern corporation. So let’s take the big swing here before we tell the story. How are those classic stories wrong?

Richard White: Well, why don’t we take the story about the transcontinental uniting America and being necessary for American development first. The transcontinental railroad, the reason the government financed it was to keep California in the Union during the Civil War, and railroads get started in [1863] when the war is still going on. But the war is long over by the time the railroads are going to be completed in the late 1860s.

So one of the things is, the first goal didn’t really work. The second thing was, it’s supposed to allow the nation to move goods across the continent more cheaply than they can do by shipping and by going across Panama. In fact, eventually the western railroads, Union Pacific and the Southern Pacific, will buy up the Pacific Steamship Company in order to raise rates because they cannot compete with the steamship company moving goods across the country.

What the railroads are supposed to do is introduce this age of competition, of individual fulfillment, of small farming. But in fact, what they do is they create large corporations, which manage to be both incredibly competitive and monopolistic at the same time. What they do is create monopolies, which control what individual people can do. They control the economy in much of the West in ways that stop competition, that stop the ability of small entrepreneurs to prosper. And in the end, what they do is create, by the early 20th century, an oligopoly. What you have is a few corporations dominating transportation all over the West. So everything they were supposed to be, they failed to do.

And the initial technology is such that, because they do not keep the infrastructure up, the original roads, by and large, are going to be the famous description of them as streaks of rust going across the continent. It’s going to be a rebuilding by people like James Hill in the 1890s, early 20th century, where they have to reconstruct these roads in a more modern form. So the railroads that come to dominate transportation in the early 20th century in many ways are very different from the corporations in the 19th century.

Thompson: You said that the motivation for the transcontinental railroad begins in the Civil War. So let’s go back to 1862, 1864, where Congress grants two corporations the right to build a transcontinental railroad. It grants these companies an enormous amount of land. It issues government bonds to finance the project. These are the Pacific Railway Acts of 1862 and 1864. You call them “the worst acts that money can buy.”

Two questions: One, why was the law such a waste of money? And two, how did this grant of free land and cheap money from the government establish the themes of the rail build-out throughout the second half of the 19th century?

White: What they do is essentially have the government take on all the risk and guarantee the profits to private corporations. They also will give the money to build these railroads to people who know nothing about railroads. One of the first calculations made by people who actually run railroads in the East is that there’s no way in the world these roads are going to pay for themselves. There isn’t the traffic for them. They’re going to be immensely costly, and even with the subsidies, they will back off. So the 1864 act has to literally double the subsidies to get them to go.

And then they tracked a series of players who will get immensely rich from this, at least some of them will, but who, at the end of it, still know nothing about running railroads. What they know about is getting subsidies. What they know about is getting loans. And what they know about is draining these corporations of profits while leaving the cost to the stockholders and bondholders. And they can do that because these railroads are also incredibly corrupt.

I mean, they don’t invent American corruption. It’s much older than that. But they bring it into its modern form. They’re the ones who create the lobby. They’re the ones who buy Congress, by and large. They’re the ones who, throughout this period, will always be giving favors to what they call their friends, who are politicians, bankers, businessmen, who, by and large, will do them favors in return.

And what they manage to do is create something which has become common in American capitalism, which is a corporation, which in and of itself takes losses, but which makes the people who run it immensely wealthy. They never really bring in the profits they promise. And when they do get profitable, as I say, it’s much later and a different kind of railroad. But the people who run them, the Big Four in the Central Pacific and Southern Pacific, Jay Gould and others, they will gain immense amounts of money.

So what you’re doing is passing on a public cost, which, in the sense that they build railroads, is building railroads which turn out to be unnecessary. In the way that they create opportunities, they’re creating opportunities which are opportunities for the railroads, not for the people who settle out there because of the railroads. And what they do is create an incredibly unstable economy.

What people forget is the great crashes of 1873, again in the early 1880s, and the 1890s. So then what you have is a boom-bust economy, which most of the busts begin with a railroad depression, and the transcontinentals are going to be central to those railroad depressions.

This excerpt has been edited and condensed.

Host: Derek Thompson

Guest: Richard White

Producer: Devon Baroldi

More Plain History Episodes