Hosts

About the episode

The University of California San Diego is one of the best public colleges in America. So it was fairly shocking when the school released a report on the steep decline in academic preparedness of its freshman. The number of incoming students in need of remedial math has surged in the past few years. These students did not fail high school math. Many of them got straight A’s. Other colleges have seen similar trends: declining mathematical ability from students who aced their high school tests.

I think that there are several ways to frame the problem we’re looking at here. One is that American kids can’t do math: That’s the headline of a recent Atlantic article by Rose Horowitch. Another frame, as Kelsey Piper writes in the online magazine The Argument, is that grades have stopped meaning anything. I think that the full story is somewhere in between. The age of grade inflation is also the age of achievement deflation. We are giving more and more A’s to students who are learning less and less.

There is a lot of talk these days about America moving into a postliterate future. One piece of evidence for this is declining test scores for literacy among students and adults. Fewer people talk about a post-numerate future. The problem here is bigger than UC San Diego. National assessments in the U.S. and even throughout the developed world show that people are getting worse at math. But why?

Today we have three guests to help us answer these questions. Rose Horowitch of The Atlantic, Kelsey Piper of The Argument, and Joshua Goodman, an associate professor of education and economics at Boston University. We talk about plummeting math scores for American students, why it’s happening, and why it matters at a moment when carbon-based humans seem to be getting dumber at the very moment that silicon-based machines are getting smarter.

If you have questions, observations, or ideas for future episodes, email us at PlainEnglish@Spotify.com.

In the following excerpt, Derek talks to Kelsey Piper, Rose Horowitch, and Joshua Goodman about the factors that might explain the decline in math proficiency across the U.S.

Derek Thompson: Kelsey, I want to get started with you. Tell me about this UC San Diego bombshell. What did the report say? And what details particularly stuck with you in your reporting on it?

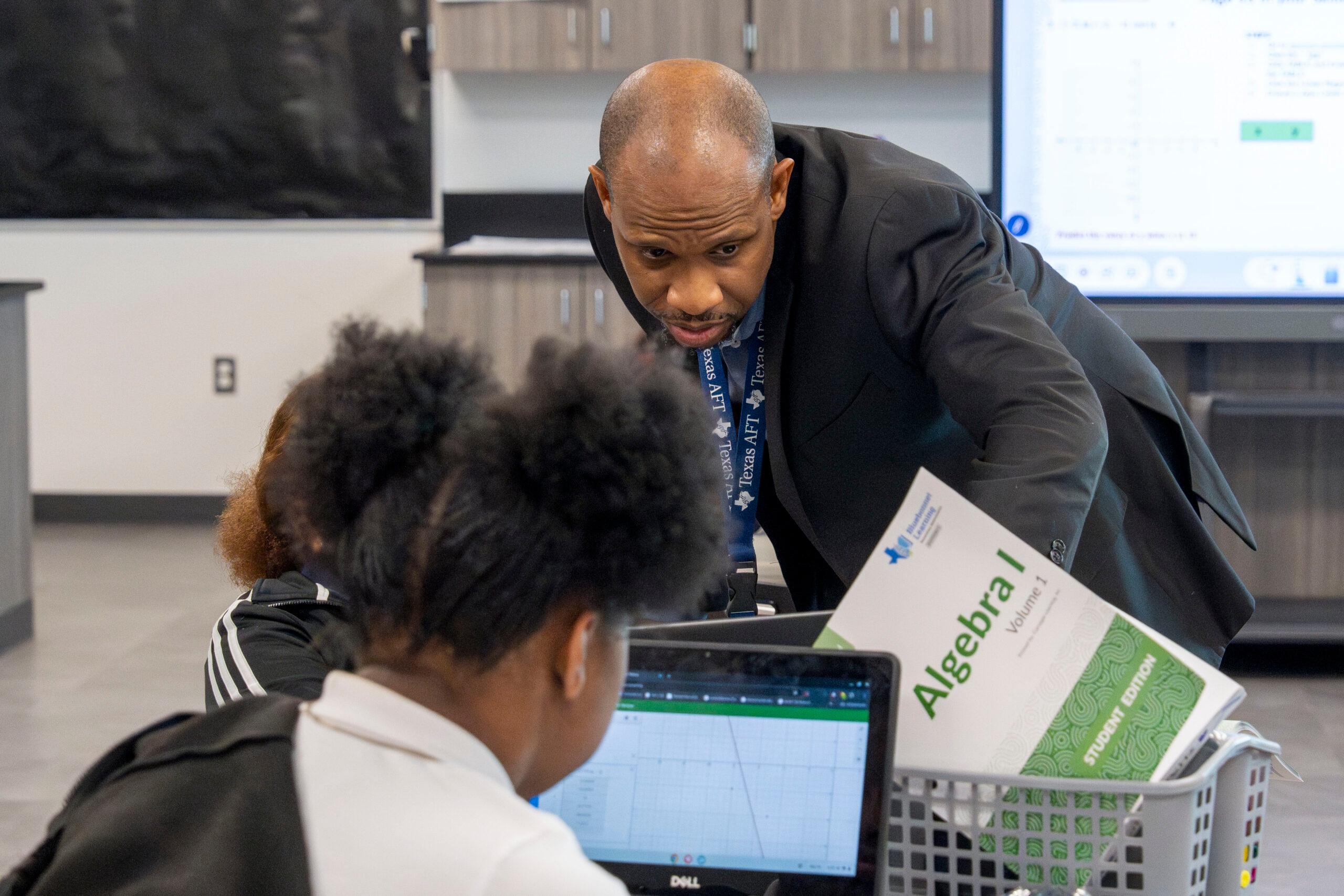

Kelsey Piper: Yeah. So there’ve been a lot of stories recently sort of breaking about education not looking good. Sometimes in the aftermath of the pandemic, sometimes about phones in schools. And then this UCSD report came out that was about a 30-fold rise in the share of students who need remedial education. It’s not quite about COVID, it’s not quite about phones, but it is catastrophic. It was really surprising to me to read through because they basically describe, you know, they used to have 30 kids in an introductory class of thousands that needed remedial math. And suddenly, it is more than a thousand kids needing remedial math. And they’re not needing remedial high school math. These are kids who need remedial elementary and middle school classes. So something went catastrophically wrong. And the thing that stood out to me about the report is that they were getting good grades in high school math. So high schools were awarding these kids top scores while, in fact, they did not have even elementary school math down. And that’s just, something has gone terribly wrong at that point.

Thompson: Rose, the problems at UCSD are extreme, but you wrote in The Atlantic that they’re not unique. Have other schools seen rising numbers of incoming students who are just, as Kelsey described, catastrophically unprepared for college math?

Rose Horowitch: Yeah. So I didn’t find any school that was similarly selective that was seeing students struggling with middle school math. But with that being said, I reached out to a lot of math professors at a lot of colleges and universities. And basically, almost all of them said that students were arriving with less math preparation than they used to have. So a lot of them were seeing students with specific skill gaps, possibly from when they went remote during the pandemic. Several reported that their students were really struggling with conceptual thinking and focusing for extended periods of time. And others were saying that their students just seemed really unmotivated to learn math. So this is something that is not as extreme as what we’re seeing at UCSD. But probably most colleges and universities are already seeing it, are already responding to it. And if they haven’t already, they will likely be in the near future.

Thompson: You reported that George Mason University in Virginia, just a few miles from me, revamped its remedial math summer program in 2023 because students arriving in their calculus courses couldn’t do basic algebra. That’s according to their math department chair. Josh, I want you to turn these statistics into a story. If you go back to the 1990s,

early 2000s, math scores are rising happily. This is not a sad story in America. It’s a story of tremendous success. And then something happens between 2010 and 2015. We go from having the highest scores in reading and math ever recorded in modern American history to the beginning of a long decline that now stretches over the better part of or larger than a decade. What happened? And when did this downward trend in the data really start?

Joshua Goodman: So I think it’s great to take the focus back a couple of decades. And just to reiterate, you’re absolutely right. From the late 1990s to about 2013, test scores, math skills as measured by test scores in the U.S. were rising very steadily, very rapidly. This coincided with an era of federal education policy that was really focused on school accountability, where there was, in 2001, a bipartisan consensus that led to the No Child Left Behind Act that emphasized for states the need for schools to use standardized tests as a metric of success. And if those metrics were not being met, there were serious penalties associated with those failures.

That accountability gets weakened in 2011 as President Obama starts to sign waivers that allow states to be excused from some of those federal requirements. And then that gets codified in the Every Student Succeeds Act in 2015, which really weakened some of those incentives further, including the emphasis on standardized testing as a metric. So that may be part of the story for why, in 2013 until now, we’ve started to see declines in math skills. But there are other things going on as well, as you’ve talked about on this show before, like the rise of mobile phones and social media. So I don’t want to put all the blame at the school accountability changes, but that’s certainly one of the stories that matches the trend both in the 2000s and then in the last decade of decline.

Thompson: We’re going to spend the next bulk of the podcast talking about why math scores seem to be declining, not just according to the nationalized tests, but also according to the reporting that Rose, Kelsey, other people are doing. But Josh, take us back to 2010, 2013, right? Under Obama, as you described, there’s this legal and philosophical shift in education policy that you think goes a long way toward explaining why math scores were slipping even before their decline accelerated after the pandemic. What was this philosophical shift? Being generous toward it, what were education reformers trying to do a decade or so ago, even if what they were trying to do ultimately failed and helped to lead us to the situation we’re in right now?

Goodman: That’s right. So I can absolutely give a generous spin to this because I believe part of the generous spin, which is the No Child Left Behind Act itself emphasized standardized testing. But the specific ways in which it did that, it said that 100 percent of students eventually had to be proficient in a given subject in order for a school to be making adequate yearly progress. That is a completely unrealistic standard to hold. So at some point, someone was going to have to change the law. Whether the particular way in which it was changed was the right way, I think, is a big open question.

And I think probably the law should have been changed to focus more on evidence that students were making progress on standardized exams, growth models as opposed to 100 percent of students having achieved a certain level. But I think that was the general philosophy, that there was something very unrealistic about the way the original law was written, combined with a set of folks who, in general, were frustrated by both federal interference in what was seen as a state and local issue of education, as well as people who just generally objected to standardized testing being used at all to evaluate schools.

This excerpt has been edited and condensed.

Host: Derek Thompson

Guests: Rose Horowitch, Kelsey Piper and Joshua Goodman

Producers: Devon Baroldi

More Plain English Episodes on Education