Hosts

About the episode

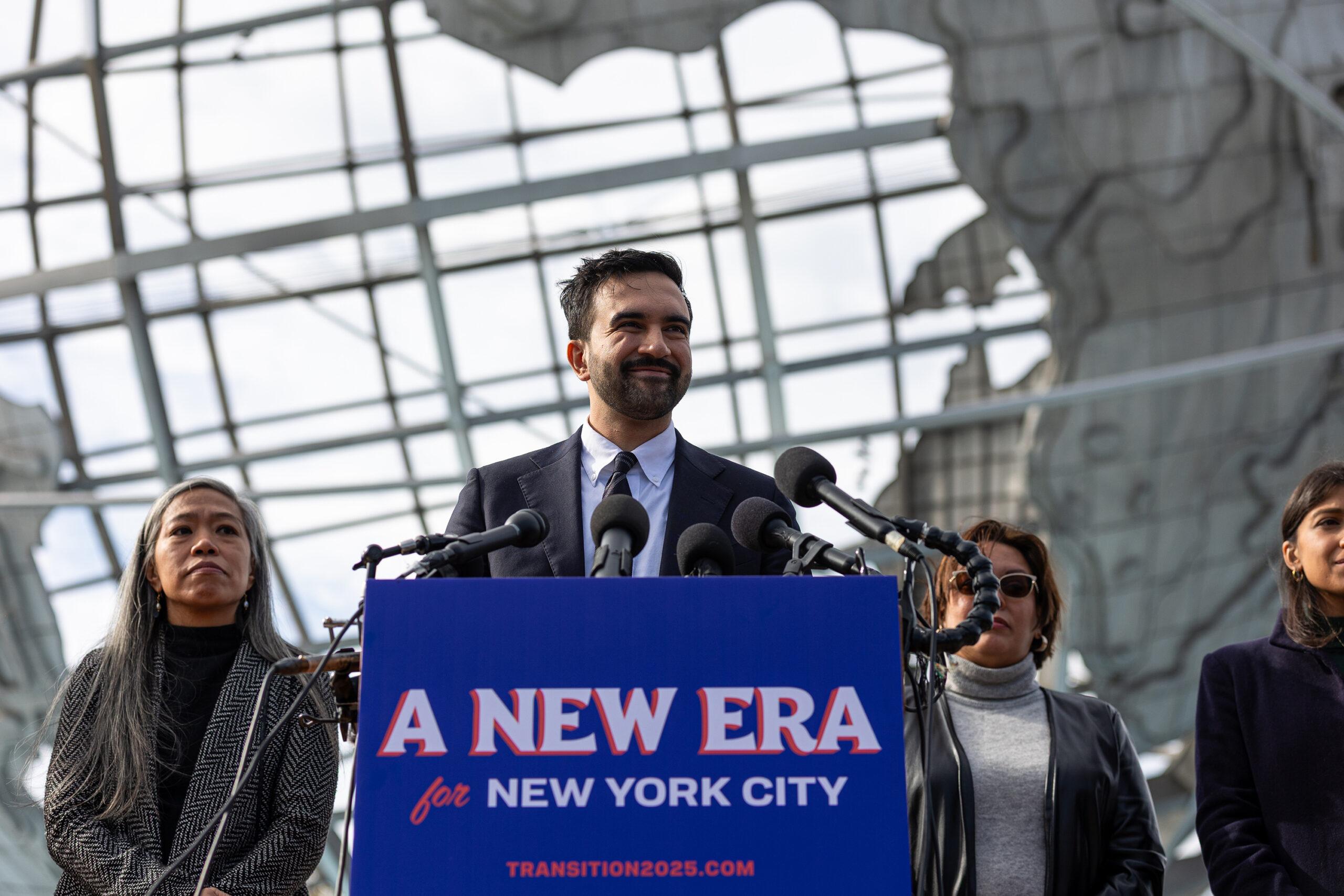

This week was a straight flush for Democrats. Zohran Mamdani completed his heroic arc to become mayor of the world’s most important city. Democrats ran up huge margins in the big governor races in Virginia and New Jersey, where Abigail Spanberger and Mikie Sherrill, respectively, won by double digits. What unified the three victories was the Democratic candidates’ ability to turn the affordability curse against the sitting president, transforming Republicans’ 2024 advantage into a 2025 albatross.

Affordability is the Democrats’ new watchword. And it’s a good one. It speaks to Americans’ direct concerns. It’s a big-tent subject, allowing a democratic socialist to offer one message in South Brooklyn and a moderate Democrat to offer another message in southern Virginia.

Today’s guest is Matthew Yglesias, a writer whose site, Slow Boring, is a must-read for me and many others who follow politics and policy. We talk about the affordability theory of everything and its weaknesses, the Democrats’ big night, the lessons of Mamdani, persuasion, moderation, and much more.

If you have questions, observations, or ideas for future episodes, email us at PlainEnglish@Spotify.com.

In the following excerpt, Matthew Yglesias explains to Derek why moderation is so important for the Democratic Party and what that moderation looks like in practice.

Derek Thompson: You’ve been part of a very loud, and I think quite interesting, online debate—not just online but really intraparty debate—over the value of moderation in the Democratic Party. And in a way, unfortunately, Tuesday’s election doesn’t give us a really clear indicator of the value of moderation because just every Democrat won. It’d be one thing if the leftist Democrats got destroyed and all the moderates won, or the moderates got destroyed and all the leftists won, but just everybody romped, and it was an amazing night for Democrats, which somewhat washes out the ability to delineate between what strategy is most successful.

That said, I would be interested for you to just state from first principles what your pro-moderation theory for the Democratic Party is and, if you could, how it might intersect with this new affordability approach that the party seems to be taking.

Matthew Yglesias: Yeah, so I think the clearest way that you see it manifesting is in turnout, right? So that if you look at New York, there was actually a spike in Republican turnout in New York City, and that’s because for all the positive things that you could say about Mamdani—he’s exciting, he got a lot of attention, he was highly viral—right-wing people also received all that attention, and they were like, “Oh, this is bad.”

He attracted a lot of opposition, and he got 50 percent of the vote, roughly, in New York City, which is not an amazing number. Now, you can say, “Well, he had to run against another Democrat.” But again, that speaks to the point that the appearance of radicalism mobilizes opposition, right? Mikie Sherrill won a crowded six-way primary, and then having won, she didn’t face a sore loser opponent because she’s a very moderate, she’s a reassuring figure from the standpoint of New Jersey Democrats.

And what she had was there was a good Democratic turnout for her because people are mad about Donald Trump. But Republican turnout was way down from 2024 because an off-year gubernatorial election is not as exciting as a presidential election, and it was hard to paint an alarming portrait of her. She’s a very regular New Jersey Democrat. It’s a somewhat blue state, and so they could throw at her, “She has X, Y, or Z sort of banal Democratic Party position,” but it’s not counter-mobilizing. New Jersey people are very accustomed to that.

Winsome Earle-Sears, similar kind of story in Virginia. She tried really hard to hit Abigail Spanberger with the sort of biggest conventional vulnerabilities of the Democratic Party, and people were just not that impressed with it. It’s the inverse of the criticism people often offer that these mainstream establishment candidates are boring. They’re also hard to radicalize people against because they seem very normal.

And anti-Trump voters are very, very motivated one way or another. The problem with this election—I mean, not problem, but if you want to look forward to the future of American politics—is these are all states that Kamala Harris won. So it’s not telling us that much about: Can Democrats eat into Donald Trump’s political support in a meaningful way? You had some Virginia House of Delegates candidates winning in Trump’s seats, so that’s probably the most positive sign for Democrats you could find.

We also don’t have an incredible amount of national media scrutiny on individual state legislature races in Virginia to tell the world all about what it is they did down there. But we see this kind of backlash all the time. The incumbent president stumbles. Particularly, he’s seen as handling the economy poorly, so his opponents are really motivated to come out and vote. His supporters are a little bit depressed. And the one thing you can do to really reactivate those depressed Republicans is to present an alarming sort of figure against them.

And there’s a lot of research on this: a David Broockman paper, I think, on this kind of counter-mobilization and an Andy Hall paper about it. And if you think about your own side or their enemies—Lauren Boebert, Marjorie Taylor Greene—these people are very motivated. People are ready to go out and beat them, and it’s easier to sort of demoralize your opposition if you’re seen as sort of moderate and inoffensive.

Thompson: I want to re-circle back to this issue of moderation because, love ’em or hate ’em, the economic populace have a very clear, and you could say falsifiable, argument. They’re like, “Run a candidate who says, ‘Blame the rich, defend the people, tax the corporations, break up the companies.’” There’s like a very clear almost formula that you can basically take, and then you can apply it across the country, and then maybe you can easily measure the effectiveness of that campaign in Brooklyn and in San Francisco and in suburban Cincinnati. But I want to understand what the pro-moderation argument actually means.

So here’s a couple examples of what it could mean plausibly. Number one is run people with moderate biographies. So Mikie Sherrill is a former naval officer, a former federal prosecutor. These are not stereotypically left-wing careers. Abigail Spanberger talked a lot in her advertisements about being the child of a military and law enforcement family. That’s number one, is run people with moderate biographies.

Number two is run on ideas that code as moderate. And “code as moderate” is a little bit of me sort of waving my hands a bit, like maybe it’s political scientists saying it’s moderate. Maybe you ask a panel of voters: What ideas are left, center, and right?

And then number three is maybe a subtle variation of number two: Don’t talk about ideas that code as very progressive. So it’s almost like it’s not about the ideas or policies that you proactively support. It’s really about what you don’t say.

Don’t say, “Defund the police.” We all know what that means. Don’t center LGBTQ issues; we all know what that means. So when you’re talking about the pro-moderation argument and the reasons for the Democratic Party to moderate, to win the Senate and to win the Congress, is it about moderate biographies? Is it about moderate issues you’re trying to make more salient? Or is it about avoiding issues that we all understand to be overly progressive?

Yglesias: So all of these things matter. Military veterans tend to do better in elections than other kinds of people. Vibes matter. Your language matters. Downplaying things can be effective. But I think that actual issue-taking, position-taking on the issues is really underrated in this sphere of time. You remember the guy who won Iowa for Democrats twice in a row after George W. Bush won them: They got an African-American law professor from Chicago, and he went to Iowa, and he won it twice in a row, but then Republicans won it back three times in a row with a real estate developer from Manhattan who wears a suit and tie every day.

And there’s this kind of obsession with, “Well, we’ve got to find the guy with the exact correct farmer vibes, and he’s going to win.” But the actual thing that happened, I think, was Obama went to Iowa, he said that marriage is between a man and a woman; he said that he was skeptical that his daughters deserved preferences in college admission because they’re the children of the United States senator, and there’s hardworking white people in Iowa who maybe deserve more consideration; and he savaged his opponents over privatizing Social Security and Medicare.

Donald Trump comes around, he’s a very extreme “figure” in so many different ways, but he actually looked at Republicans’ vulnerability on Social Security and Medicare, and he disavowed those positions. And he ran a race against Hillary Clinton, and then later against Biden and Kamala Harris, where he was like, “These people are soft on crime, and they favor lax immigration enforcement.” He reframed what the argument was about in terms of his pitch and his strategic issues, but he also changed the Republican Party’s position to be one that more voters in Iowa agreed with, and it drove Democrats nuts.

They’d be like, “This fraud, this fancy guy with his private plane.” Just like Obama drove Republicans nuts. And I think it’s because the issues actually matter more than a lot of people want them to believe, because if you yourself are an activist and you have really strong convictions on the issue, what’s most convenient for you is to say, “You know what? We’re going to get a guy who has just the right look and just the right biography, and he’s going to sell my ideas all over the country.” And I think successful politicians don’t really do that.

Mamdani, this is clearly a guy with significant convictions and ideological commitments, but he saw that his glaring weakness was that people didn’t trust him on crime and public safety. So he disavowed defunding the police. He committed to retaining [Jessica Tisch] as police commissioner. He met voters where they are, not just on a level of vibes, et cetera, et cetera. But they had a real objection to him. And he has been trying to answer that objection. And I think everybody knows that the success of his mayoralty will depend in part on: Can he deliver on public safety?

If the crime rate soars the way his critics were saying it would soar, that’ll be really bad for him. And so he’s probably going to work hard to make that not happen. And if you look at Trump, he campaigned saying that prices were going to go down when he won, which was, that’s what people wanted to hear. And since he’s been in office, he hasn’t been able to make that happen, and as you were saying, that’s his biggest problem right now, is the issues. Nothing about his personality has changed. The Democrats haven’t even changed that much, but this central promise of Trump’s campaign now looks false to people, and that makes a big difference.

This excerpt has been edited and condensed.

Host: Derek Thompson

Guest: Matthew Yglesias

Producers: Devon Baroldi