Hosts

About the episode

In the past few weeks, for the first time in my life, I’ve seriously thought about the 21st century not being another American century.

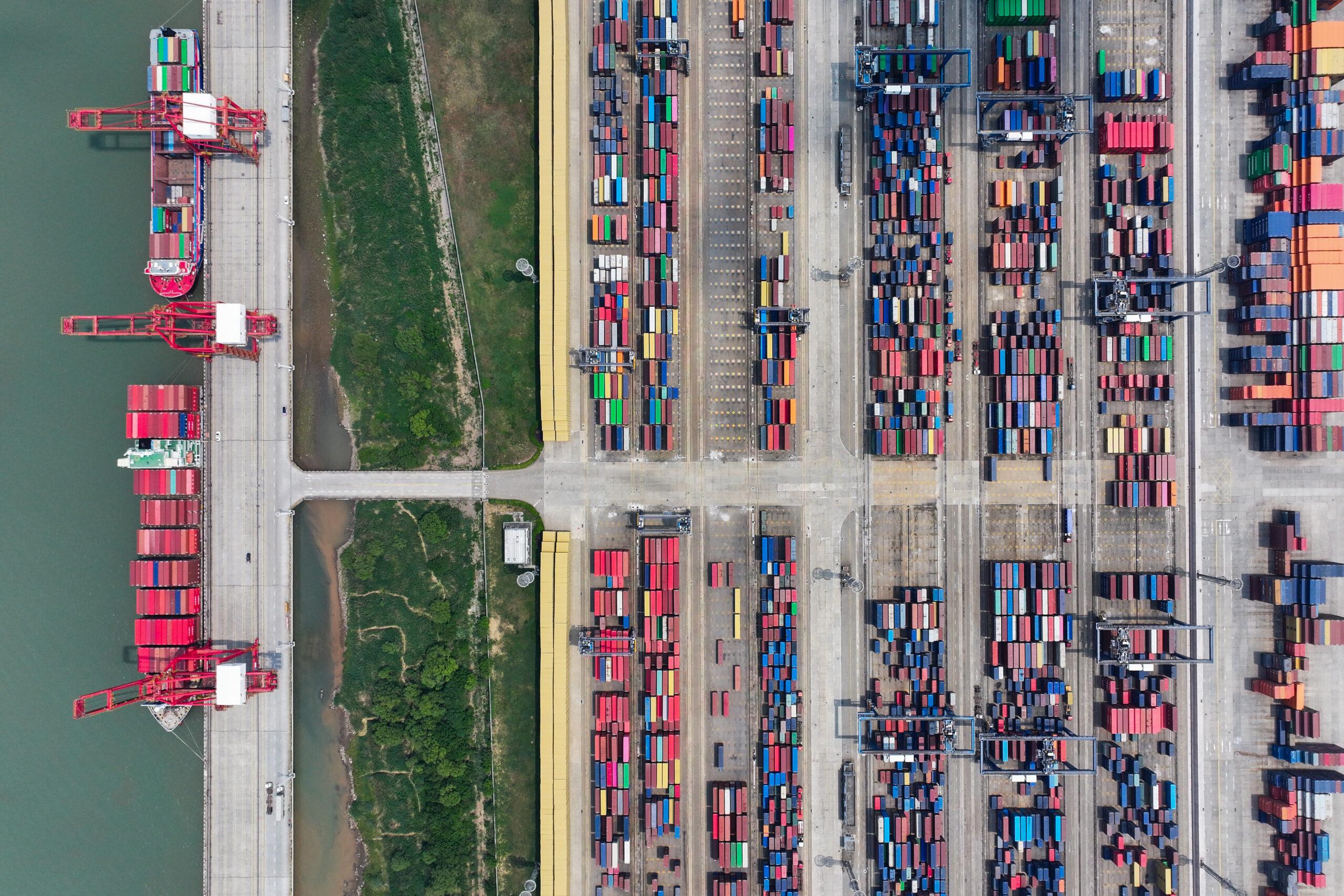

A recent essay in the journal Foreign Affairs by Rush Doshi and Kurt Campbell put things as starkly as I’ve ever seen. Some people are still stuck in a mode of thinking about China as being a place that just makes things of little value and significance. But Made in China means something different now. Technologically, China dominates everything from electric vehicles to fourth-generation nuclear reactors. Militarily, it features the world’s largest navy. Its shipbuilding capacity is 200 times as large as America’s. In a world built of cement and steel, China makes 20 times more cement and 13 times more steel than the U.S. In a world whose future will be full of electric vehicles, batteries, drones, and solar power, China makes two-thirds of the world’s EVs, three-quarters of its electric batteries, 80 percent of consumer drones, and 90 percent of solar panels. In a world where wars are won by the largest militaries, consider that China’s navy will be 50 percent larger than the U.S. Navy by the end of the decade.

Today’s guests are Kurt Campbell and Rush Doshi. Both men served on the Biden National Security Council. Campbell is the chairman and cofounder of The Asia Group. Doshi is director of the China Strategy Initiative at the Council on Foreign Relations and an assistant professor at Georgetown University.

If you have questions, observations, or ideas for future episodes, email us at PlainEnglish@Spotify.com.

Summary

In the following excerpt, Derek talks to Rush Doshi and Kurt Campbell about the potential outcomes if China surpasses the U.S. as a world power.

Derek Thompson: Kurt Campbell, Rush Doshi, welcome to the show. Rush, you’ve said that the 2020s are a critical decade for the relationship between China and the U.S. What makes this decade critical?

Rush Doshi: Yeah. Well, at the beginning of the Biden administration, a lot of folks got together, read the intelligence, read the tea leaves, and came to a conclusion that basically if we didn’t take certain decisive action in the next few years, really in this next decade, we could end up in the following situation. We could be behind China technologically. We could be dependent on China economically. We could be defeated by China militarily in the Taiwan Strait or elsewhere. And those are sort of the stakes, really, of the next decade. And as the next decade goes, so might the next century

Thompson: And Rush, what are the stakes here more concretely? Are we concerned about Chinese dominance on economic grounds just because we want America to remain the biggest economy in the world? On technological grounds, is it that we’re jealous about the frontier on AI or ships? And militarily, what is truly at risk here? We don’t want an expansionary China taking over Taiwan, pressing further into the eastern and southern regions of Asia? What are the stakes?

Doshi: Well, I think basically there’s a question of what the world is going to look like in the future. We want a world where by and large America is prosperous, and that involves technological leadership, which has often fueled our productivity and our economic prosperity. It also is a world where we’re not dependent on China, a potential adversary, for critical inputs. Right now we’re dependent on China for everything from medicines to key electronic components to critical minerals. We are not sure that that’s probably in our long-term interest. Militarily, it’s been a long-standing goal for the United States that one of the world’s most dynamic and prosperous regions, Asia, not fall under the hegemony of a rival who might not have our best interest at heart. That’s really at stake if the U.S. is defeated in the South China Sea or the East China Sea, or especially the Taiwan Strait.

So the stakes really are essentially the shape of the future. And since the end of the Second World War, the U.S. has been the world’s leading state. If the U.S. is no longer the world’s leading state, there are implications for America’s quality of life. And let me just say one last thing. We could paint a little bit of a picture of what this could look like, but an America that sort of deindustrializes itself and that doesn’t lead in technology is an America that is essentially a large version of a kind of maybe Latin American republic. We have commodities, we have real estate, we have tourism, we even have transnational tax evasion, but we don’t have leadership in the things that make this country unique, special, powerful, influential, and prosperous for everyday Americans.

Thompson: That all sounds very wise, but it’s also very high level. Talk to me as if I am just a typical dad in America. I don’t know that I care that much about Taiwan. I don’t know that I care that much about the technological frontier in robotics or the number of patents that various countries get to brag about when they go to their international science conferences. What I want is for America to grow and get richer. I want my kids to grow up in a country where they are safe and their incomes are rising as well, and they can afford the good life. How do all of these things that you’ve talked about that are at stake with the U.S.-China showdown, how do they connect to my interests to just raise a happy and healthy family in a growing economy?

Doshi: That’s a great question, and I think I’d start by saying that America is maybe only 5 percent of the world’s population. And everything we enjoy, the quality of life that we have, what we’re used to, what we’re accustomed to, is something we take for granted. But it’s a product of hard work, investments in American prosperity, investments in American technological leadership, and a system that kept the world largely safe for the kind of economic activity that has generally enriched this country. All of that, and with it, your quality of life is essentially at stake if the U.S. mishandles the China challenge. And for the first time since the end of the Second World War, the U.S. could really fall behind, and that will have implications for the quality of life of every person in the country.

Take, for example, what happens when other countries have lost the mantle of being hegemon. It isn’t as if when the United Kingdom declined from being a global great power to essentially what is a middle power now that things went well for them. Their quality of life in many ways is higher than it was back then, but lower than a lot of other parts of the rest of the world. They’re not as productive. They don’t have the same kinds of jobs and industry that the United States enjoys today. And so decline is a real problem. And what we’re talking about is relative decline, yes, but also, in a certain sense, potentially even absolute decline. If the U.S. loses the mantle of hegemony, that means everybody’s quality of life gets worse. That means you’re dependent on others for your prosperity, for your technology.

But just take a step back. Imagine a world where, for example, China steps into our shoes, they become the world’s leading state. What does that look like? Well, it’s a world where there’s Chinese military bases all over the map, even in the Atlantic, where early in the administration, we had to push back on that right on our doorstep. Economically, it means that we’re dependent on them for the things that we rely on to live the good life, which gives them enormous control over essentially how we govern ourselves potentially, or what we choose to do economically.

Technologically, it means we’re getting all the best stuff from them. We’re behind for the first time, really in a century, America no longer a technological leader. And then politically, it means the default settings of the international system, which are abstract for us, we don’t think about it day-to-day as we live our lives, but they’re generally favorably inclined towards democracy. Well, maybe that flips, and this is a world which leans more in the direction of autocracy and the values that we care about find pressure not just from without, but also from within. Those are essentially the stakes.

Thompson: Kurt, the history here is so interesting because it’s my understanding that the prevailing wisdom in U.S.-China relations used to be predicated on economic engagement, on costless economic engagement. The U.S. welcomed China into the World Trade Organization. The thinking was that trade with the U.S. would make China more like America—richer, more capitalist, more liberal, more open—and also that, by the way, access to China would make Americans feel richer, too. We’d buy cheaper toasters, cheaper clothes, each dollar would go further, and there would be no cost to our quality of life. What has happened to that easy theory of engagement in the last 10 to 15 years?

Kurt Campbell: Yeah. Well, thank you very much, and it’s great to be with you all. And I appreciate the chance of partnership always with my friend and colleague Rush Doshi. So first of all, let me just say that the idea, the logic, of engagement was pervasive. And in fact, one of the hardest things to challenge in international relations were the concepts and beliefs behind that engagement. I think it became clear in the 2000s or in the early parts of the second decade of the 2000s that China was determined not just to get more wealthy and more powerful, but to challenge the United States’ place on the global stage.

And it was not enough just to see China surpass the United States, but frankly, in strategic councils in Beijing, a desire for the United States to actually be defeated. I think the initial idea was that this reflected perhaps parts of the Chinese system, but ultimately there was still an appreciation and belief in engagement and working in partnership with the United States. I think over time, Derek, that most of those views have basically fallen away, largely as a result of just experiencing the world and some of the things that Rush has laid out more directly.

This excerpt has been edited and condensed.

Host: Derek Thompson

Guests: Kurt Campbell and Rush Doshi

Producer: Devon Baroldi