“I’m out in Orange County because everyone in L.A. is absolutely psycho and batshit crazy,” internet gossipmonger Nik Richie told me.

We were at a Newport Beach golf club within the gated community where Richie lives. He seemed to know every last posh California WASP, and our walk through the club’s lounge was peppered with friendly backslaps. He led me to a wide patio overlooking a lush, mountain-studded vista. “I feel like this is my sanctuary,” Richie said, shielding his dark eyes from the sun’s glare.

Not that he is hiding. Since 2007, Richie has overseen his gossip blogging network, The Dirty, as it grew from an Arizona-based joke to a much-hated, news-breaking indie media company that destroyed political careers, provoked Hollywood scandals and Vine star drama, and turned Richie into a micro-celebrity in his own right.

Over the past few years, The Dirty has receded in prominence and popularity, and he is now in the middle of a radical overhaul. A few months before our meeting, Richie relaunched his infamous gossip website, shifting it from posting rumors about ordinary people to conventional celebrity news. Richie made his name by encouraging his readers to rat each other out by emailing him “the dirt” on one another. He’d block-quote his favorite emails in blog posts, often accompanied by images of the scantily clad, inebriated, and unfaithful. While many of these posts are still archived, the site took on the appearance of a generic news blog in January. Rather than posting user-submitted gossip, a small staff hired by Richie chases news. Seven people work for the revamped Dirty, which has a small office near Fashion Island in Newport Beach. “I’m trying to pick people that have a chip on their shoulder,” Richie said. “It’s like Billions. I’m like Axelrod.”

Instead of snide takedowns of random college girls, it published a Girls retrospective. Instead of ragging on teen moms, it’s chasing Teen Mom 2 exclusives. To hype the overhaul, Richie announced that Melania Trump’s anti-cyberbullying campaign had provoked his radical about-face, that The Dirty would clean itself up in an effort to become a TMZ mini-me.

Meanwhile, a production team announced in March that it was partnering with Richie to produce a scripted show about his life as a digital tattler, based on his 2013 memoir, Sex, Lies and The Dirty. So Richie isn’t forsaking his gossip-blog past completely; he’s simply grasping for any spotlight he can wrangle, and he sees an opening: Gossip has lost its luster, and “fake news” is both a buzzword and a real scourge. Richie wants to gain traction and break news through exclusive interviews, so his scoops are verifiably true. He sees the media landscape as untrustworthy, so rotten that there’s room for a formerly reviled bottom-feeder to carve out a respectable niche.

The Dirty and its owner have a bad reputation for giving people bad reputations. Now, Richie is pinning his hopes for renewed success on scrubbing his site of its more unsavory elements. There’s a certain aptness to his quandary: The man who made a living ruining other people’s names now wants to refurbish his own into a mainstream, family-man success story. But can the internet forget? Perhaps the more relevant question is whether it will still care.

“Nik Richie” is not his given name. The 38-year-old blogger was born Hooman Karamian. Richie has a froggy voice and an intense stare, with a shaved head he likes to rub. He still favors the slightly oversize polo shirts that were popular during his wildest years. If I were feeling bitchy, I’d say he had a Napoleon complex — and I felt bitchy as we sat down to talk. I’d just finished his sleazeball fairy tale of a memoir, which chronicles his rise as a “civilian gossip blogger.” As far as self-aware memoirs of substance-addled male degeneracy go, Richie’s makes Tucker Max look like David Carr. There’s a “Niktionary” appended to the book so fans can ape his slangy vocabulary; it’s a collection of racial slurs and jokes about fat people, poor people, ugly people, and lesbians. (A himstitute is a “tranny prostitute,” while a WNBA is “a tall female who is manly.” Those are two of the milder entries.)

Before founding his website, Richie attended Cal State Fullerton. Instead of studying, he spent most of his time as a hanger-on in the Orange County punk music scene and attempted to become a band manager. Managing didn’t work out, but Richie participated in a scheme wherein he’d take money from aspiring musicians and promise to connect them with labels, without ever doing so. “I sold them, scammed them. I fucked these people over the way the industry fucked me, and I was good at it,” he explains in his memoir. He moved to Arizona and assumed the name “Corbin Grimes” because his birth name “didn’t sound right in the hip-hop world.”

In 2007, bored with his work life and in the habit of frequenting nightclubs in Scottsdale, Arizona, he launched a hyperlocal party gossip forum website called Dirty Scottsdale. He solicited pictures of the drunkest and most disorderly partygoers on his club circuit. He chose the handle to hide his real identity and to position himself as a nastier counterpart to celebrity gossip blogger Perez Hilton, who had already established himself as the dirt purveyor to the stars. (Richie gets mad when people call him Hooman now, so thoroughly has he adopted his reality-TV-inspired moniker.) To distinguish his bit from Hilton’s, Richie posted about people whom he perceived as fame-hungry rather than those who were truly famous.

“We were going through the whole Paris Hilton and Nicole Richie phase of life, where everyone in their subcultures and their cities thought they were personally popular out at the nightclubs,” Richie rasped. “I thought it would be really funny to make fun of these people because they wanted attention.”

“[He was] inspired by my nom de blog,” Perez Hilton told me.

Dirty Scottsdale was the first of many city-specific satellite websites, from Dirty Newport to Dirty Vancouver. (Apparently, Vancouverites had such an insatiable appetite for slander and scandal it got nicknamed “Vandirty”; it was perennially the most-frequented microsite, according to Richie.) He even had a site in Paris. Richie created a central hub, simply known as The Dirty, and selected the juiciest items to be featured on that page. The site found an eager audience. As it grew, The Dirty branched out into celebrity news, but its origins and bread-and-butter were “civilian gossip” with a focus on college and nightlife hubs. The site was skewed toward students in the featured towns, like coeds from Arizona State and the University of Arizona. It influenced imitators, like the college-focused JuicyCampus and College ACB. And given that it debuted early, The Dirty dominated the market; it had 20 million page views a month by 2013, according to Arizona Central. But not without controversy.

Richie framed The Dirty as a sort of irreverent extension of call-out culture, wherein he’d expose wrongdoing as a way to hold people accountable. To this day, Richie maintains that targeting ordinary people was meant as a wake-up call. “If people want to judge me, that’s fine. Do I deserve it? I think I do. Am I a mean person? I don’t think so. Do people need to look inside themselves and say, ‘Hey, why am I getting blasted on the internet?’ I think they do.”

As the website’s popularity increased, it accumulated so many posts about so many people that “reputation management” companies, which charge money to hide embarrassing internet search results (in some cases removing the posts completely), began offering help to remove people from the website. There’s a cottage industry built around cleaning up the reputations of The Dirty’s targets.

The Dirty’s frequent targets were often ordinary college students, including Alicia, a 25-year-old who appeared on the site as a teenage freshman in Michigan. (Alicia is a pseudonym.) The site posted a photo from her Facebook page alongside nasty comments about her face and body. “It was super petty, and very ridiculous,” she told me. After she emailed to have the post removed, it was taken down within two weeks. While she wasn’t particularly traumatized by the incident, she said that because submitting images to The Dirty had developed into a popular method of venting anger and jealousy at her university, she knew other people with far more negative experiences.

“I’ve had a couple other friends on there, and their posts were a lot more hurtful, about real situations that had happened, that they weren’t proud of,” she said. “They were deep jabs that really affected them.”

Richie assigned nicknames to the people who were submitted to the site most frequently. “We’d call them ‘Dirty celebs,’” he said, noting that several Jersey Shore cast members had appeared on his site before starring on the MTV show.

I asked Richie if he still keeps in touch with his Dirty celebs, particularly the ones he wrote about in his book, women he gave names like “Leper.” “I tried to keep my distance as much as I could,” he said, shrugging. When I mentioned I’d read his memoir, which opens with an explicit chapter about having sex with these women, he clarified. “I did sleep with a couple of them, but that was not by choice, that was by drunken choice. And I wish them all the best. I kind of thought, like, I was doing them a service.”

Richie curated his content, plucking the juiciest entries from thousands of emails to decide what would appear on the sites. He posted lurid accusations of naughtiness, from credit card scams to performing sex work while carrying an STD, although he maintains he did have some boundaries about what to post and what to withhold. He often blurred out genitals, and he would remove the addresses of the various website targets.

“Revenge porn, rape, and people saying ‘AIDS’ — that was the stuff we were trying to filter out,” Richie said. “So I acted as a moderator — an editor, I guess you can say, that’s what everyone said — and that caused a lot more trouble than I was expecting.”

Richie was notorious enough that after an investigation, The Smoking Gun identified him in 2008 by his given name, and released his mugshot and police report from a DUI he’d received the same year. “I went into this deep depression,” he said. “But then it completely backfired on them.” While Richie says he hadn’t wanted his identity outed, the exposure raised his profile, and the site’s traffic spiked. And with that, Richie began erasing Hooman Karamian in favor of his public persona.

As The Dirty grew, its tipoff emails started implicating celebrities as well as regular people. In 2008, The Dirty ran a photograph showing an underage girl serving Trump Vodka at an event, which led to a minor scandal for the future president. It ran several stories about Carrie Prejean, the 2009 runner-up in Trump’s Miss USA pageant. Prejean had answered a question about same-sex marriage by declaring that “opposite marriage” was what she believed in, winning hearts in the Bible Belt. The Dirty acquired seminude photographs of the pageant royalty, tattering her conservative image. Prejean was later stripped of her crown. It galvanized scandals about Ashton Kutcher (alleged infidelity), Charles Barkley (DUI bust), and a variety of other actors, athletes, and politicians. It became the defendant in defamation lawsuits.

The Dirty even had an in-house political scandal. Richie’s Scottsdale clubbing pal, onetime U.S. representative Ben Quayle of Arizona, worked as a correspondent for The Dirty, writing barbed comments about local debauchery under the pseudonym “Brock Landers.” Quayle, the son of former vice president Dan Quayle, found his political career in jeopardy when Politico connected him to his old gig. At first he denied it, calling Richie a “smut peddler,” but he eventually confessed to writing for the site.

The increased exposure led to increased criticism, including a lacerating interview with Anderson Cooper, in which Cooper questioned Richie’s morality. “Not that I have nightmares over it, but it replays in my head over and over,” Richie said. “It was never my intention to be this guy. I wasn’t trying to be a bad person.” Then again, the Cooper interview is noted on the back cover of Richie’s book, so if it mentally tortured him, he also willingly used it as a self-promotion tool. He seemed genuinely perturbed by Cooper’s words when we spoke, but then again, he was talking to a reporter in an attempt to convey a more wholesome image. Richie also repeatedly told me that he lacked normal emotional responses, suggesting without outright stating that his former, frequent callous behavior reflected a limited psychological register, which left me even more suspicious that his decision to bring up Cooper was motivated more by a desire to capitalize on the CNN anchor’s high-profile name than any lasting anguish.

Richie is, after all, a skilled schmoozer. After his identity was released, Richie made a healthy sideline doing club appearances, essentially going on tour as a media bad boy. He was, by his own account, even more poorly behaved than many of the people whose foibles he broadcast.

“I would ruin people sometimes out of fun, and it was just not healthy,” Richie said, before launching into a story about how a Canadian man pulled a gun on him. It was a wickedly entertaining and completely unverifiable story, the type Richie excels at telling.

In 2009, Richie posted a rumor from a reader that former Cincinnati Bengals cheerleader and high school teacher Sarah Jones had had sex with several Bengals players; the post also implied that she had spread sexually transmitted diseases in her pursuits. Later that same year, Jones sued Richie and The Dirty, and initially won an $11 million default judgment — but her lawyers had mistakenly filed the case against the wrong company, which meant the verdict was unenforceable. She tried again, and in 2013 she won a $338,000 judgment against The Dirty.

The judgment roused a surprising cross section of supporters for the gossip website, including most of the major players in the online speech community, who were alarmed by the implications of The Dirty’s loss. Richie was heartened by the support he received from major tech companies in his appeal. “I’ll tell you what, we had everyone. We had Google, we had Facebook, we had all the big boys,” he said. “They all had my back.”

He’s not exaggerating: Amazon, AOL, eBay, Google, Facebook, Gawker Media, BuzzFeed, CNN, Curbed.com, Twitter, LinkedIn, Microsoft, TripAdvisor, Yahoo, the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, Tumblr, the American Civil Liberties Union, the Electronic Frontier Foundation, the Center for Democracy & Technology, and Yelp all filed amicus briefs in support of Richie’s appeal.

Richie was a frequent target of defamation lawsuits, and as a website operator, he had already argued in previous cases that he was legally shielded by Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. (This is the same statute that has protected a variety of different internet entities, from Twitter to Facebook to Backpage.com.) The statute gives online publishers immunity from liability for content posted by third parties. It’s why people can’t sue Twitter if an egg tweets something defamatory or harassing at them. Without the statute, many of these entities would be unable to survive the opening of the legal floodgates, which is why it is seen as integral to protecting speech online. It is separate from the First Amendment, but it can work in conjunction with the First Amendment to keep the internet’s major channels of communication open.

“In the free speech community, we were upset and concerned about that being a new standard under Section 230,” Electronic Frontier Foundation lawyer Sophia Cope said. “Section 230 was meant to protect intermediaries and give them leeway to act as editors.”

The 2013 decision for Sarah Jones was overturned on appeal the next year. A three-judge bench ruled that Richie and The Dirty are protected under the Communications Decency Act and are not liable for the comments written by third parties, citing Section 230 as the reason.

In the middle of the case, Jones pleaded guilty to misdemeanor sexual misconduct for having sex with her then-17-year-old student in 2011. She was not required to register as a sex offender, but she was banned from teaching. (Jones and the student eventually married in 2014.) Her scandal had no impact on her lawsuit against Richie. Jones could’ve been the most famous and badly behaved person in the world or a cloistered nun who had never even heard of The Dirty — it wouldn’t have mattered. What got the case overturned was the basic idea that because Richie did not write the words, The Dirty was not liable for them.

This was not the first time a website of a high-profile gossip columnist had been found not liable in a case like this. In 1998, AOL was found immune regarding the postings of its gossip columnist, Matt Drudge, after political operative Sidney Blumenthal and his wife attempted to sue for defamation. But while AOL was found immune, Drudge was not; he eventually settled with Blumenthal. In the case of The Dirty, the website operator and the author of the columns were essentially one and the same, but since Richie chose to block-quote emails from other people for his “columns,” he was found not liable for the content of those emails. His case is a strong precedent for an incredibly broad interpretation of Section 230 immunity.

But I was struck by just how broad that interpretation was in Richie’s case. Yes, he had not written the words in his posts, but he’d sorted through thousands of emails to decide which ones to block-quote and feature, and then he editorialized at the bottom of the featured emails with his own take. But in broader interpretations of the statute, that still qualifies The Dirty as a publisher and platform, and doesn’t qualify Richie as a writer.

“Like a lot of unpopular speakers in the past, [The Dirty] really took an important leadership role in protesting freedom of expression for everyone. They have been quite out there taking one for the team when it comes to protection of controversial speech,” First Amendment lawyer Marc Randazza told me. “Richie seems to me to stand very firm on his principles.”

Randazza compared Richie favorably to Google executives, in particular, whom he believes to be craven. At one point, he indicated that he believed Google cofounder Sergey Brin would commit a heinous, unpublishable sex act “if he thought it would raise the bottom line 10 percent.” “I do believe that every person in the upper management at Google would do that,” Randazza added. (I had not mentioned Google.)

“Richie is taking advantage of what I’d understand as something like a liminal state,” said law professor Danielle Citron, who wrote the book Hate Crimes in Cyberspace. She said that Section 230 needs to be altered to discourage site operators from primarily hosting defamatory material or content that invades privacy.

“He’s in the gray zone. And so he worked it for years. It’s really just despicable. The whole business model is despicable.”

Law professor and digital free-speech advocate Eric Goldman warned against looking for ways to weaken Section 230. “Once one plaintiff finds a gaping hole, thousands of other plaintiffs will pile in behind them,” he said. “You have to recognize that any hole will become the gaping hole that will destroy Section 230 in practice.”

“People were saying, ‘You are the Larry Flynt of the internet,’” Richie said as we discussed his legal victories. “I started agreeing.”

“When I won the Sarah Jones vs. Dirty World case and I set precedence, she didn’t even try to take it to the Supreme Court. I sat there and thought, ‘OK, finally, all this hard work is finally paying off. I’m the First Amendment guy for internet, and I have something.’”

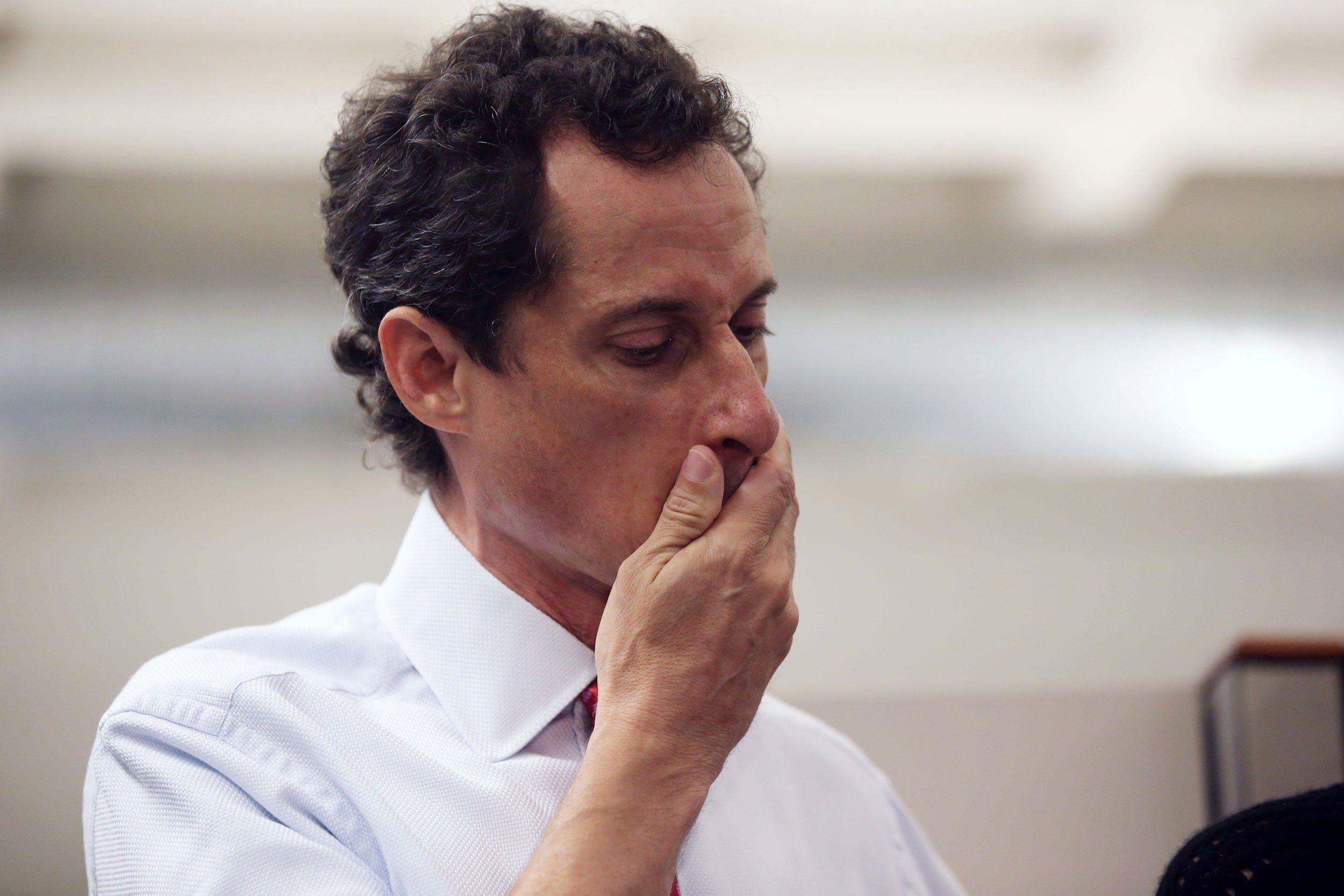

Though his website originally relied on amplifying small-town innuendos and rumors, Richie’s greatest hits were stories he spread about people in positions of power and influence. In 2013, The Dirty broke its biggest story ever: Anthony Weiner’s second sex scandal, when the world learned that Weiner allegedly used the moniker “Carlos Danger” to conduct digital affairs. Richie had been receiving emails from Sydney Leathers, a college student in Indiana who told him she’d been having phone sex with the disgraced former representative long after he’d claimed to have ceased his extramarital digital flings. Richie hesitated to publish anything, because she couldn’t offer photographs showing Weiner’s face. “Just his lower regions,” Richie explained.

In an attempt to verify the goods, Richie compared the feet in the dick pics he was sent to the feet in previously published photos of Weiner. They matched. He took a gamble and wrote the story. It went viral. “When I saw the CNN ticker and it said, ‘TheDirty.com breaks Anthony Weiner scandal,’ I just started crying. I literally started crying,” Richie said. “As much as people say that I’m a hack, I’m not a real journalist, what we’re doing is wrong — we exposed him. And he had to admit the truth.”

Right now, The Dirty’s young staff are hustling to find exclusives. They mostly come up with small items about reality stars, as well as some celebrity sound bites and random hard-news scooplets, like the emergency message that parents received in a recent school shooting in San Bernardino, California. However, The Dirty’s chances of breaking another high-profile political story are likely to be complicated by Richie’s convoluted stance on what to post.

Another splashy item that The Dirty broke was news of Hulk Hogan’s sex tape in 2012. Richie posted images from the tape along with his own commentary. The tape is indelibly linked to another media organization, however. “We broke the Hogan thing, and Gawker took the fall for it, which still blows my mind to this day,” he said.

The Dirty posted images of the Hogan sex tape in April 2012, six months before Gawker posted a short video clip. While Hogan sued Gawker Media and won a $140 million judgment against the media company, bankrupting it, he did not sue The Dirty, even though Richie had posted content from the tape first. “Hogan and I actually became friends out of the whole thing,” Richie said. (Hogan did not immediately respond to a request for comment.)

Richie told me that he was aware of a conspiracy against Gawker Media, and he gave it his blessing. “We knew certain people on the stand, like A.J. [Daulerio, Gawker’s editor-in-chief at the time], would fail. I’ve done jury trials, Joe Francis has done jury trials, the people that they went after, like Peter [Thiel] — you just don’t do it. You just don’t,” he said. “They crossed the wrong people. And I can say I had a part in that, and that makes me proud.”

As far as “the wrong people” are concerned, Girls Gone Wild creator and entrepreneur Francis — whose antipathy toward Gawker is already well documented — was the only name Richie named. Francis, for his part, has claimed that he encouraged Richie to erase the metadata on The Dirty’s sex tape posts as part of his campaign to make Gawker look like the primary bad actor.

I asked A.J. Daulerio if he was aware of Richie’s role in Gawker’s legal woes. “I don’t know anything about that,” he said.

The Dirty often trafficked in sex scandals about athletes, which meant that its content often overlapped with Deadspin. I have written for Deadspin, and I used to work for Gawker Media, now known as Gizmodo Media Group, so I asked Richie why he didn’t have an affinity for a fellow gossip-slinging media company, particularly one that had posted the same story as he did. Richie said he was not happy about the way Gawker Media treated him. “Jezebel and everyone was shitting on me,” he said, noting that Gawker leaked his book proposal. “It was very New York, very ‘We’re better than you,’ very ‘We run the world and our media company is untouchable.’”

“I can understand why he felt underappreciated, because he was doing interesting things when a lot of people weren’t doing interesting things,” Daulerio said. “I really admired what he did when he was at The Dirty.”

While Richie is still happy to pontificate about the scandals of New York media, he is less inclined to break news about other circles. Richie is a Republican, and The Dirty has started dipping into political coverage, most of it pro–Donald Trump. “Trump is absolutely psychotic, but if he can get the job done, there’s no harm no foul,” Richie said. Even though the website’s most famous scoop and Richie’s proudest moment hinged on exposing the sexual misconduct of a politician, he says he isn’t eager to release any information about Trump that could be considered damaging.

“I’ve had a lot of Trump stuff that I haven’t posted,” Richie said. “I don’t think it’s relevant to the time we’re in right now. We’ve had a lot of stuff that could’ve killed him.”

Although he’s openly allegiant to The Donald, Melania Trump’s anti-cyberbullying campaign, Richie admits, isn’t the real reason he decided to overhaul The Dirty. “I was like, now’s kind of a turning point, not that Melania Trump’s words rang true, but I was like, the media are bullies.”

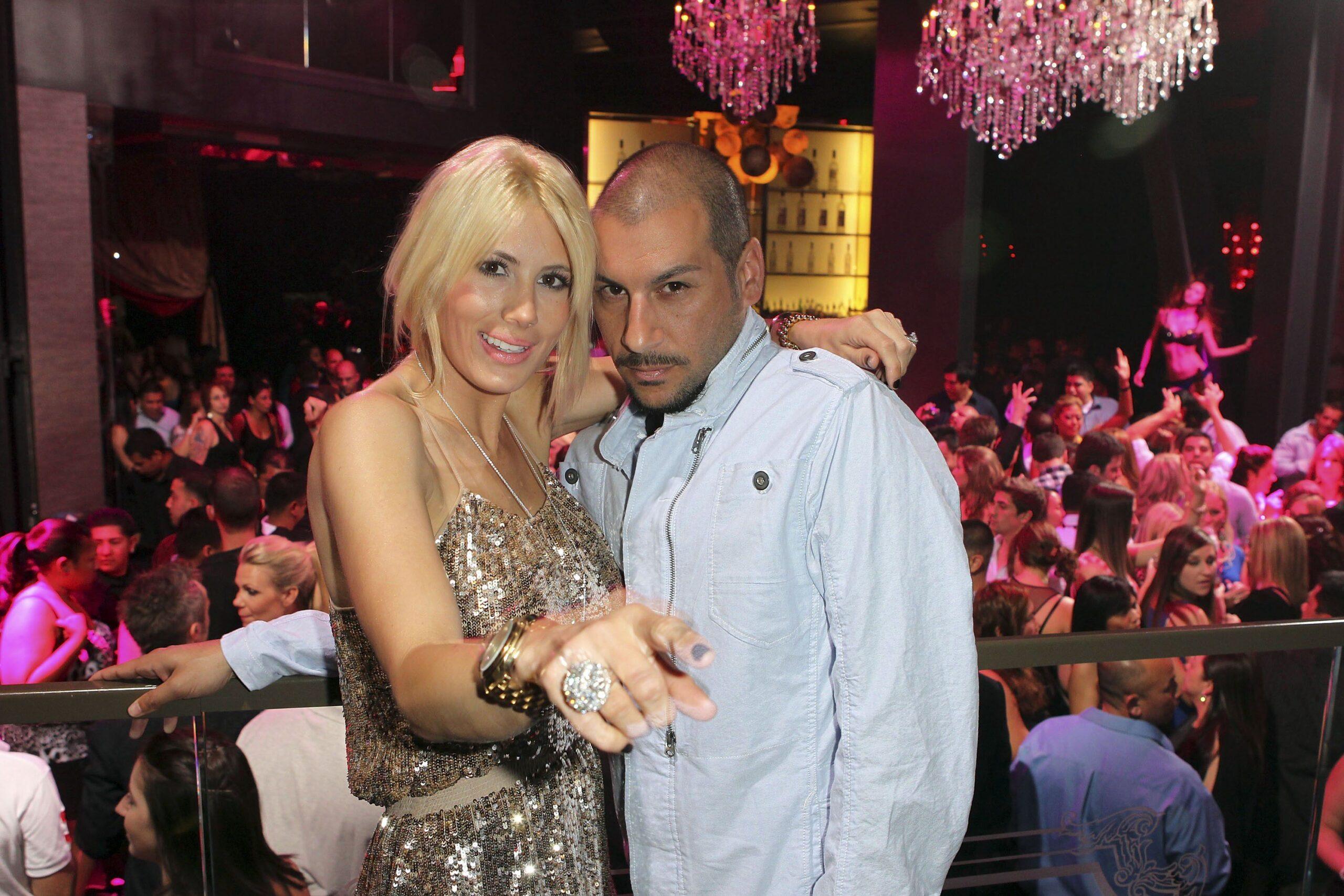

Richie married ex-Bachelor winner Shayne Lamas in a tabloid-fodder Las Vegas chapel wedding within 24 hours of meeting in 2010; they’ve been together for seven years, and now have two small children, Press and Lyon. (Press’s first name is an homage to journalism.) Lamas insisted that the children’s last name be hyphenated. “She just doesn’t think it’s a real last name,” Richie said.

In a poetic twist, Lamas is exactly the type of sort-of-famous socialite Richie began The Dirty to mock. After winning The Bachelor, she clung to the industry with a short-lived Kardashians-style family drama (2009’s Leave It to Lamas) and appeared on VH1’s Couples Therapy with Richie in 2012. (Couples Therapy is basically a Celebrity Rehab With Dr. Drew knockoff for Z-listers in relationships.) She’s not famous for being famous; instead, she occupies the increasingly crowded zone of people who are famous for playing themselves on television.

Lamas became pregnant with their second child in 2013, but she suffered from a rare condition in which the fetus grew outside of her uterus. She required emergency surgery; she lived, but required a hysterectomy, and the baby did not survive. She enlisted her stepmother Shawna Craig to act as a surrogate for their next child. Craig, who is appearing on the upcoming reality show Second Wives Club, gave birth to Lamas and Richie’s son Lyon.

Richie told me he wants to be able to be a coach on his children’s sports teams, to live a more professional and respectable life.

“When my son died, people just sent me photos of dead fetuses. People are not nice,” he said. “I’m not nice, either, so it doesn’t bother me. But it does bother my family, it bothers my lawyers, it bothers my friends, and it bothers my employees; they don’t want to be part of something like that, so I’m giving everyone the opportunity to be better.”

And there’s another reason. “About a year and a half ago I got diagnosed with multiple sclerosis,” Richie said. “I now am in a weird place where I’m like, OK, doctors are telling you you’re going to be in a wheelchair by, like, 45.”

The diagnosis galvanized Richie to go full-throttle in his quest to beat TMZ and make a name for himself as a breaker of news. “Not to say karma, but it’s starting all over again. I’m in a new Wild Wild West. I’m starting all over. I don’t know what my future is. Before, I was always like, ‘Am I gonna go to jail? Am I doing something illegal?’ Now it’s like, ‘Am I gonna be able to walk? Am I gonna be able to kick a soccer ball with my kids?’

“I’m on this weird kick to find a cure. And not be a Jamie-Lynn Sigler, who goes out there and is like, ‘I have MS, and everything’s going to be OK,’” he said.

“[MS] is not OK. It’s not what people think it is. There’s deep, dark pockets of depression. There’s days where your motor skills don’t work. If you ask me to throw a baseball, I couldn’t do it. The only thing I can still really use is my mind,” Richie said. “I don’t have time. Can I make time? I think I can. I think I can do something special.”

Emails blasting normal people for degenerate behavior still roll in, but The Dirty stopped posting them in January, when Richie announced the revamp. Instead of posting about spray-tanned clubgoers, it’s posting about spray-tanned Real Housewives. When asked about the site’s traffic, Richie says the website is bringing in around “3 million” without specifying unique views or pageviews. (Alexa puts the monthly figure at around 239,000 uniques.) The Dirty is an independent media company, though not because he wants to stay indie as much as because its reputation is still slightly radioactive. Richie hopes to eventually sell it.

There’s an old quote about the media that is commonly sourced from an 1893 Chicago Evening Post humor column: “The job of the newspaper is to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable.” When Richie started The Dirty, he afflicted people who had signifiers that represented comfort to him: carefree attitudes, club clothes, drug habits, robust sexual appetites. The reason The Dirty was so frequently cruel was that it confused the idea of people acting like rich, famous socialites for a night with their actually being rich, famous socialites.

And now Richie seems to be confusing his mission once more, choosing to afflict no one in favor of providing comforting, snack-like entertainment news. Richie wants to break stories, but will not break news that hurts the people in power whom he likes. This certainly does not make him unique among journalists today, but it does represent a strange evolution of his original mission.

The Dirty’s Anthony Weiner exclusive is an example of what it looked like when the gossip blog turned its attention toward people who deserved scrutiny. Even if Weiner’s wife, Huma Abedin, had agreed to an arrangement that allowed him to continue to carry out sexually charged relationships with college students, the story was still notable because it proved that Weiner was lying to his constituents. As Weiner’s pile of scandals grew increasingly sordid, at one point causing the FBI to examine a batch of emails to determine whether they were pertinent to an earlier investigation into Hillary Clinton’s private server, it has become even more apparent that breaking that story has only grown in significance since Richie cried tears of joy watching CNN.

Apart from the inherent contradictions in launching a news-breaking website that won’t break news about its favored powerful figures, The Dirty is reinventing itself in a hostile climate for gossip blogs. During the 2000s, The Dirty entered an online gossip ecosystem in blossom, not yet chastened by high-profile court cases and public backlash against invasions of privacy. Leaked sex tapes were celebrity currency, and publishing the crotch shots of public figures was seen as distasteful but not automatically despicable. From the internet’s inception until now, cultural conversations about cyberbullying, privacy, and misogyny have shifted how gossip sites, and the web in general, operate. It’s not just that Richie wants the respectability that comes with publishing politely, it’s that he might need to be nicer in order to survive.

What’s more, social media sites have changed readers’ habits; instead of bookmarking and frequently visiting their favorite blogs, many people who keep up with celebrity and political gossip tend to get their information directly from social media, whether it’s accounts like The Shade Room or simply the president of the United States’ Twitter feed.

“Gossip blogs really don’t have a place anymore. There’s not that audience that there used to be,” said Matt James, who runs the website Pop Culture Died in 2009 and closely tracks how the internet’s celebrity gossip scene has evolved. “People get their news from looking at their Twitter feed.”

James said he does not think The Dirty’s chances of success at a relaunch are high, partly because of its reputation, but mostly because the ecosystem has changed.

Perez Hilton sees celebrity news as a claustrophobic space now. “So many people are doing what so few were doing back in the day, because they’ve realized that celebrity news now is mainstream news,” he said. “I won’t say [Richie’s] going to flop, but I will say that he already started the year off on a bad foot by falsely proclaiming that Hugh Hefner was dead, and I don’t even think he ever retracted that. But hey, I once quite infamously said Fidel Castro was dead, and I never retracted that, either.” (Richie actually erroneously proclaimed Hefner dead in 2016.)

Hilton also doesn’t think that Richie’s past will be that much of a hindrance. “The general public has no idea who he is,” Hilton said. “I’m not saying that to be petty or mean, that’s just an honest assessment.”

There’s no obvious place for a sanitized, declawed The Dirty, but Richie still wants to take a shot at building a media empire on more than gossip. Richie gestured with his hand across his eyes as he talked about his dreams of going legit.

“Hopefully, I can create a great staff and infrastructure where The Dirty can be its own brand, and it can grow,” Richie said, craning his hand over his eyes again as the sun set. “And Nik Richie can go away in his wheelchair.”